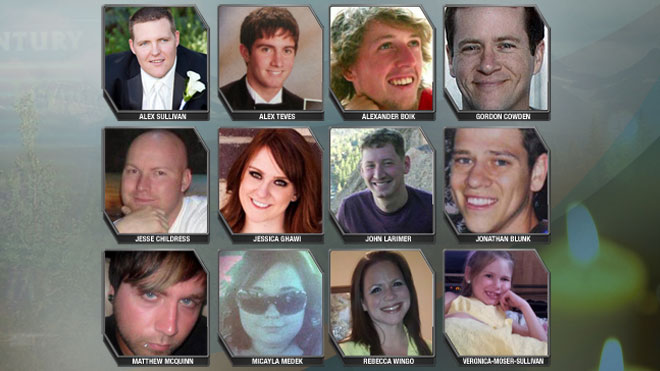

Last Friday, just after midnight, the opening of one of the most-anticipated movies of the year, The Dark Knight Rises (the final installment of the Nolan Batman trilogy), was tainted by news that a man entered a midnight showing of the film in Aurora, Colorado. The man threw gas cannisters on the floor, fired a shot in the air, and then opened fire randomly into the audience with an assault rifle, a shotgun, and a Glock (or possibly two) handgun. Seven minutes later, the alleged shooter, James Egan Holmes (a 24-year-old neuroscience graduate student at the University of Colorado, Denver), was in custody — but not before leaving 12 dead and 59 wounded.

My first reaction to the news was one of shock, horror, and sadness. Not only had 12 lives been snuffed out violently and senselessly, but Holmes had chosen to commit his crime here, like this, at this: at a midnight showing of a comic book movie.

The murder of innocence

Like most fanboys and fangirls, I’m a regular at midnight showings. There’s a certain magic that comes from staying up until midnight to be one of the first people in America to see a movie on opening day. There’s a camaraderie shared as you and other moviegoers collectively embrace the insanity of waiting over two hours in line so that you can ensure that you have one of the best seats in the house. There’s an innocent joy and devious mischievousness — like children who have joined forces to stay up way past bedtime at a sleepover party. Midnight showings cater almost exclusively to my demographic: mid-to-late twenty-somethings who are escaping the reality and responsibility of adulthood, and instead are recapturing part of our youth by indulging in an almost child-like wickedness. Midnight showings are small, intimate, spontaneous comic-cons; they are gatherings where we can fly our nerd flags proud, where we can wear our vintage Batman t-shirts and collector’s edition Star Trek communicators without shame, and where cosplay is acceptable outside of San Diego. We are the comic book and video game and Saturday morning cartoon generation, and at midnight showings, all of those things we were supposed to have grown out of are, for the briefest of hours, “cool” again.

A shooting spree at a midnight showing of a comic book movie strikes home not just because of the senselessness of the violence and the death. James Holmes did not only (allegedly) murder 12 innocent lives and forever scar 59 others, but he also murdered the very innocence, wonder, and magic of the midnight showing.

I attended a 10:30pm showing of The Dark Knight Rises last Friday evening, less than 24 hours after the Aurora shooting. We were second in line, behind another couple who arrived just as we did. The four of us joked and laughed about waiting for two hours for a movie, made small-talk with the frazzled theatre manager, and jokingly cried out “earmuffs!” and collectively covered our ears as the previous showing let out so that we could avoid hearing spoilers. And yet, I couldn’t help but feel some apprehension as I waited in line. I surreptitiously scoped out the emergency exits, and confess that I experienced some relief that the Milford police department had stationed a uniformed police officer right outside the IMAX theatre for our late-night screening.

Some people just want to watch the world burn

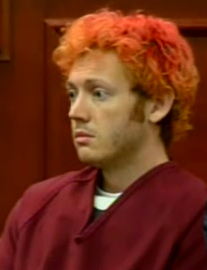

In the wake of the shooting, there have been countless pundits who have raced to connect Holmes’ actions with his choice of the latest Batman movie. Dana Stevens of Slate asks “Why There?” and postulates that the dark, modernistic dystopia and violence of Dark Knight was a deliberate backdrop for Holmes’ actions. CNN cites unnamed sources saying that Holmes, hair dyed red, identified himself as “the Joker” moments after his arrest, a claim that seems to be at least partially corroborated by in-court images of Holmes at his hearing today.

Dana Stevens quips: “James Holmes didn’t burst into a screening of Happy Feet Two.”

However, I think it’s dangerous to draw a causative relationship between the actions of a certifiable mad man (and any man would have to be insane to commit this kind of crime) and The Dark Knight Rises and the Batman mythos. Holmes didn’t burst into a screening of Happy Feet Two, but he very well might have. He didn’t choose to target a screening of The Dark Knight Rises because of the film’s violence or modernity; he targeted a screening of The Dark Knight Rises because he is insane.

There is simply no sense in trying to draw a specific a priori connection between Holmes’ actions and the movie he chose to target. That would be attempting to apply rational thought to irrational behaviour. Trying to blame Holmes’ actions on the Batman movies is about as meaningful as trying to blame Holmes’ actions on the pursuit of a doctoral degree in neuroscience, or on the use of cheap red hair dye.

That being said, I think there is value in trying to draw post hoc parallels between the Batman mythos and Holmes’ connections. Because, like it or not, the Batman story is highly relevant to the events that unfolded in Aurora Friday evening, and the months leading up to it.

For example, there is one relevant passage in the Nolan Batman mythos that I think is worth invoking here: in The Dark Knight (the second installment of the Nolan Bat Trilogy), Alfred recalls the story of a crazed bandit that he fought in his past, and whose motives cannot be fathomed. There is no rhyme or reason to men such as this. They cannot be pleaded with, negotiated with, or understood. There is no logic to their psychosis.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=efHCdKb5UWc

Without glorifying James Egan Holmes or his actions, these words nonetheless resonate: some men just want to watch the world burn. And they would be just as satisfied lighting their match at a screening of Dark Knight Rises as at a screening of Happy Feet Two.

Gun Control and the Bat

In The Dark Knight, the Joker speaks of the unique power of murder that go against a larger social “plan”; how the life of a gang-banger is not seen as equal to the life of a politician.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pfmkRi_tr9c

These words ring true. The last few years have seen mass killings that have struck a particular nerve within the mass consciousness — 9/11, Columbine, the Virginia Tech Massacre, the Tucson shooting of Gabby Giffords, the Norway shooting spree, and Aurora. In the wake of those massacres, this nation (and other nations) have been preoccupied with asking the question of why — why would anyone kill these people?

Yet, in our struggle to understand the motives of madmen, it’s hard to ignore one simple fact. These deaths all share one thing in common: the victims were people who “aren’t supposed to die” (this despite the fact that hundred, even thousands, have died in the same span of time as a result of war, poverty, disease, natural disaster, or violence in a non-First World country). Do we grieve more for their loss than for the countless killed in the genocide in Darfur over the last decade, or for those who died as part of the civil uprisings in Syria this past week, or the thousands who die of gun-related deaths in this nation’s capital of Washington D.C. every year?

The honest answer to this question is unsettling.

Both sides of the gun control debate have clamoured in the wake of the Aurora shooting to speak about how gun control, or the lack thereof, would have prevented the deaths of the 12 young moviegoers on Friday night. Advocates of the Second Amendment have been quick to defend gun rights in this country. Senator Russell Pearce of Arizona, for example, wrote a Facebook post suggesting that an armed moviegoing audience would have stopped Holmes’ shooting spree:

Had someone been prepared and armed they could have stopped this “bad” man from most of this tragedy. He was two and three feet away from folks, I understand he had to stop and reload. Where were the men of flight 93???? Someone should have stopped this man. Someone could have stopped this man. Lives were lost because of a bad man, not because he had a weapon, but because noone was prepared to stop it. Had they been prepared to save their lives or lives of others, lives could have been saved. (emphasis added)

Yet, in Pearce’s home state of Arizona (where gun laws are incredibly lax), a sitting Congresswoman was shot in the head just a year and a half ago. The six deaths and 12 wounded, including Congresswoman Gabby Giffords herself, were not prevented by armed bystanders. Indeed, Slate recounts how a bystander with a licensed CCW permit nearly shot one of the heroes of the Tucson shooting.

Early Friday morning, in Aurora, Colorado, James Egan Holmes burst into a packed movie theatre which was screening a movie about a man whose life was forever changed by gun violence. Holmes wore state-of-the-art military-style body armour, and he brandished weaponry that (as far as we can tell) were all legally purchased. He fired countless bullets into the theatre using predominantly an AR-15 assault rifle and nearly 6000 rounds of ammunition.

His bullets killed and wounded more than 70 moviegoers, including audience members in a neighbouring theatre. Would an armed audience have stopped Holmes? Or would an addition of more guns to an already chaotic scene of panic, assault rifles, and tear gas have only added to the bloodshed?

In the wake of this tragedy, this country has discouraged a politicizing of this massacre. But, I disagree with this point of view: how can it be respectful to the victims if we are willing to mourn them, but unwilling to face the ugliness that led to their deaths?

In our shock and grief following such tragedies, we must nonetheless strive to hold ourselves to a higher standard: to let rationality prevail over emotion and bloodlust, to respect the lives of the victims rather than glorify the acts of their killer, and to ask ourselves whether the protecting the rights of a madman to legally purchase an AR-15 — which has no purpose other than the taking of human life — is in the spirit of the Second Amendment. Perhaps, in our shock and grief, we should not shy away from the political discussion that surrounds this horrific crime, but instead face it head-long. The twelve young lives lost Friday morning didn’t just die; they were killed, coldly, brutally, and heinously by a madman wielding a legally purchased gun.

We owe the victims of Aurora the courage to face this truth.

Actor Jason Alexander wrote over the weekend as part of his plea for greater gun control:

Then I get messages from seemingly decent and intelligent people who offer things like: @BrooklynAvi: Guns should only be banned if violent crimes committed with tomatoes means we should ban tomatoes. OR@nysportsguys1: Drunk drivers kill, should we ban fast cars?

I’m hoping that right after they hit send, they take a deep breath and realize that those arguments are completely specious. I believe tomatoes and cars have purposes other than killing. What purpose does an AR-15 serve to a sportsman that a more standard hunting rifle does not serve? Let’s see – does it fire more rounds without reload? Yes. Does it fire farther and more accurately? Yes. Does it accommodate a more lethal payload? Yes. So basically, the purpose of an assault style weapon is to kill more stuff, more fully, faster and from further away. To achieve maximum lethality. Hardly the primary purpose of tomatoes and sports cars.

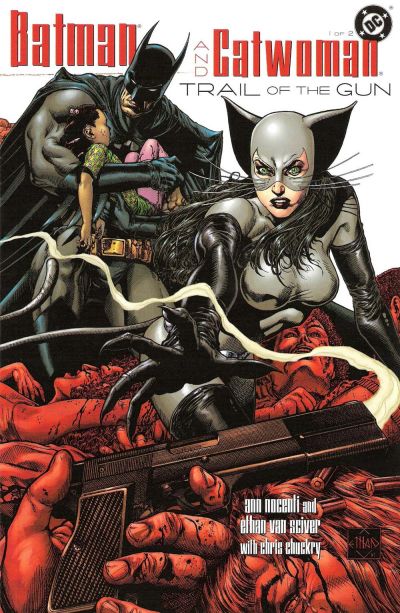

In our race to draw parallels between Holmes’ actions and the Batman mythos, why can we not draw a lesson or two from Batman himself? Rather than to link Holmes to the “dystopic modernity” of the Nolan Bat-verse, perhaps we can instead strive to learn from the Batman character, and his perspective on guns? Would this not be a more meaningful parallel to make, if we must make one?

Like a young Bruce Wayne, a senseless, horrific shooting robbed us of human life, but of our innocence. For the rest of his life, Bruce seeks to come to terms with the scars obtained after a mad-man uses a gun that murdered both his parents, and his childhood.

In Batman Begins, Bruce succumbs briefly to a need for blood and vengeance. He arms himself with a small handgun, intent on shooting his parents’ murderer at a parole hearing. But, he soon comes to the realization that the gun he holds in his hand will not protect him from killing and death, and will not assuage the pain he feels after his parents’ murderer. He realizes that no one, not even he, should hold the destructive power of life and death in their hands. In the years following, Batman frequently underscores his abhorrence of guns.

This theme of the destructive power and responsibility of guns is a powerful undercurrent in the Batman mythos, and appears also in The Dark Knight Rises (don’t worry, no spoilers here). Batman’s story advocates powerfully for greater gun control, not only through the devastating impact that a single handgun had on the young Bruce Wayne’s life, but also through his subsequent rejection of guns in his fight to rid his city of criminals, and the crimes they commit.

Again, I return to Dana Stevens’ emotional question: why and why there? We may never know why Holmes committed the crime he (allegedly) committed, just as we will never fully grasp the motives of the 9/11 terrorists, or why Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold murdered 12 students and a teacher at their high school one morning, or why Seung Hui-Cho barricaded himself in a college classroom and killed 30 students and professors before turning the gun on himself.

While there is no immediate answer to “why there”, Holmes’ choice of “there” necessarily invokes the anti-gun message of the Batman mythos. In my final reaction to the Aurora shooting, I can’t help but wonder: how many people have to die before this nation is willing to have the real, and difficult, debate over guns and gun control? Further, I cannot escape the simple fact: had James Holmes been armed with tomatoes on Friday morning rather than an AR-15, there are 12 young people who would likely still be alive today.