By Guest Contributor: Ju-Hyun Park (@Hermit_Hwarang)

A disturbing antifeminist wave has swept through many Asian American digital spaces in the past few years.

Though misogyny in self-professed progressive and radical Asian American spaces is nothing new, the specific iteration that has developed presents a departure from past forms. Whereas older Asian American antifeminisms would seldom engage feminist theory, the new Asian American antifeminism co-opts the work of Black and Asian feminists in service of narratives that position the prioritization of Asian American cishetero men as a truly “feminist,” even “intersectional,” venture.

In recent months, Medium, Nextshark, and YOMYOMF have been flooded with a torrent of articles exemplifying this antifeminism. These pieces have ranged from screeds decrying Asian feminism as complicit in White supremacy to fictionalized accounts of East Asian women marrying neo-Nazis. Generally speaking, these articles have focused on Asian women in interracial relationships with White men, and have presented these pairings as evidence of a hidden sexual agenda in Asian feminism, and Asian women’s enthusiastic participation in the structural oppression of Asian men.

These arguments are not new. They have existed as undercurrents in Asian American politics for some time. However, the willingness of popular Asian American news media outlets to provide a platform for these ideas is cause for alarm. By offering space for these pieces, sites like YOMYOMF and Nextshark are proliferating an antifeminist ideology amongst their respective audiences. This development not only threatens Asian feminists, but also Asian women in general and our movement as a whole. It therefore demands a response.

I have identified some of the base assumptions, arguments, and outright myths of the Asian American antifeminist narrative. I will debunk them here:

MYTH 1: Asian women have more social privilege and power in US society than Asian men.

Many Asian American antifeminists assert that Asian American women are more privileged than Asian American men. Most of these arguments confine their definitions of “privilege” to the relative sexual desirability of Asian American women and men to non-Asian people. Yet, such a view relies on an understanding of social power so reductive that the word “privilege” becomes a misnomer. “Privilege” is a term for the unearned social, political, and economic advantages of certain groups that arise through the oppression and dispossession of targeted populations. When we use the term “privilege,” we are talking about the policies, practices, and patterns in a society that that affect the overall quality of life and death for different groups of people.

While sexual desirability (which is very different from sexual power) is informed by social power, it does not comprise the whole picture on its own. If we are to discuss privilege in comparative terms, we must consider how it manifests in all areas of life. For the sake of brevity and quantifiability, I’ve chosen to focus on four particular areas: economics, media representation, political representation, and health.

Economics

However one chooses to look at it, Asian American men have a definitive economic advantage over Asian American women. Speaking in the broadest terms, Asian women make 73 cents for each dollar an Asian man makes. When the data is disaggregated, the pay disparities are even higher for some ethnic groups. Nationwide, there are nearly three Asian men in executive positions in private companies for every Asian woman at the same level. Asian women are more likely to be employed with lower salaries, more likely to have their careers stalled, and more likely to face employment discrimination.

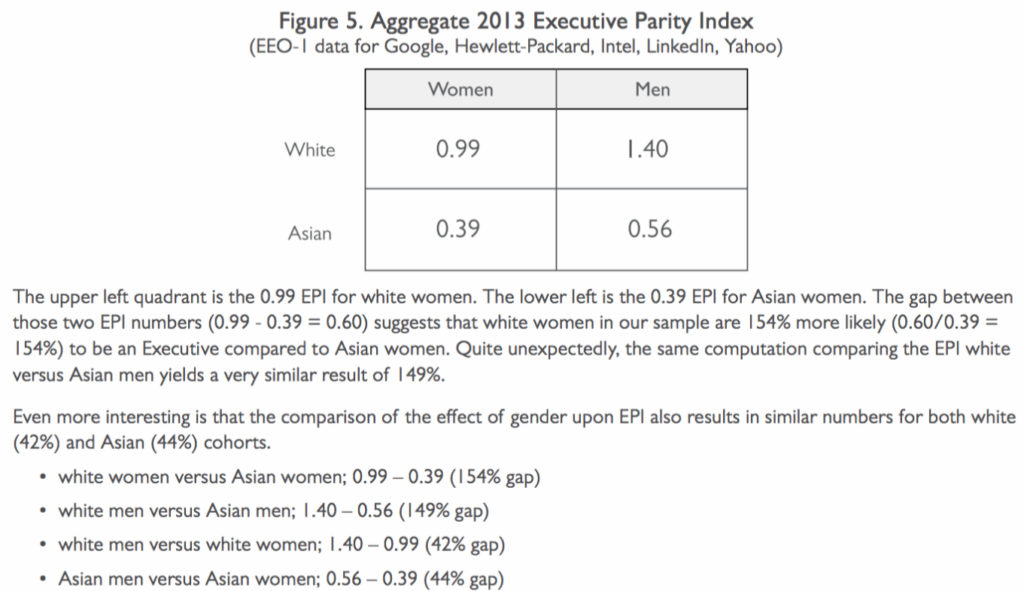

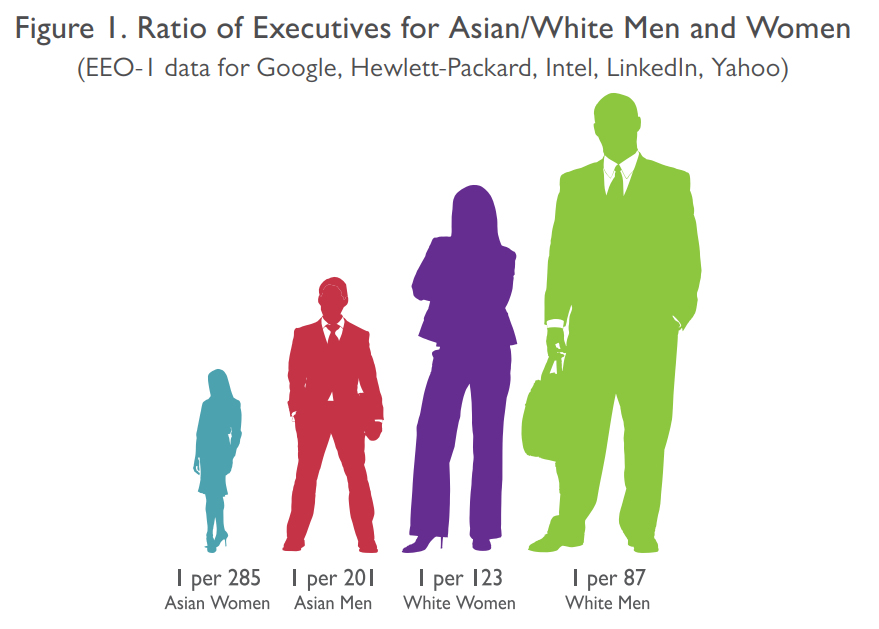

According to a study by ASCEND, Asian women professionals comprise 13.5% of the workforce at Google, Hewlett Packard, Intel, LinkedIn, and Yahoo!, but only 3.5% of executives. Underrepresentation in upper management positions is far worse for Asian women than for White women or Asian men. White women were 154% more likely to be executives than Asian women, whereas White men were 144% more likely to be executives than Asian men. Looking intraracially, Asian men were 44% more likely to be executives than Asian women, while White men were 42% more likely to be executives than White women.

While these differences may seem negligible, it is important to recognize that unlike Asian men or White women, Asian women must contend with racial and gender discrimination in their careers. As a result, Asian women in these companies face tremendous disparities compared to White men.

If this is what Asian women can expect in a field with a high share of Asian workers, one can only imagine what professional conditions are like for Asian women in other industries where they are less well-represented.

Some argue that the reason for this persistent gender disparity is an alleged disinterest that women have for STEM fields. Yet, such bioessentialist assertions ignore the reality of structural barriers in STEM. Findings from the National Science Foundation suggest instead that disparities in hiring and career trajectories reflect a double-bind of race and gender-based discrimination—hurdles distinct from those that Asian cishet men face in their STEM careers.

Economic abuses of Asian women also persist far beyond the tech industry. Women from Asia are the largest group of people trafficked internationally into the United States. Garment and semiconductor factories operating in the United States often employ Asian women under illegal and dangerous working conditions. Asian women are also much more likely than Asian men to be employed as domestics, and are therefore more vulnerable to the abuses common in this highly unregulated market.

Across Asian ethnic groups, Asian women fare worse than Asian men when it comes to economics. The impact of racialized misogyny on Asian women’s career trajectories, incomes, and employment is quantifiably more detrimental than the effect of gendered racism on Asian men.

Media

Many of those who argue that Asian American women are more socially and politically privileged than Asian American men cite media representation as an example. They suggest that Asian American women are “winning out” when it comes to representational politics, particularly in mainstream media. Such arguments equate the allegedly greater visibility of Asian American women with greater political power and privilege.

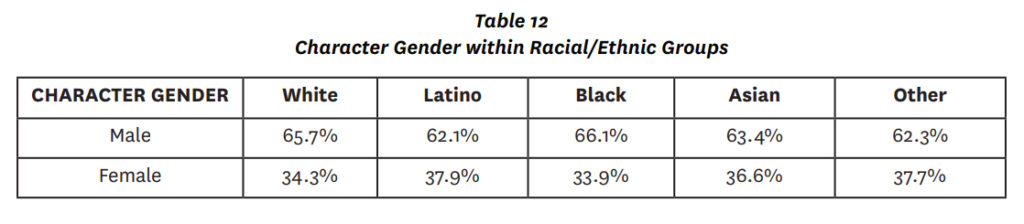

Yet such allegations do not align with the data on the subject. Asian women in media are actually far less likely to be represented in fully-developed speaking roles compared to Asian men. The Annenburg Center at the University of Southern California found that of all speaking roles for Asian characters, only about a third were given to Asian women.

Asian American women must also contend with their own gendered stereotypes in media representation. Many Asian feminists have critiqued Hollywood for its portrayals of Asian women as exotic, self-sacrificing, and submissive objects available for the satisfaction of the (usually White) male protagonist. It is also worth noting that even within Asian and Asian American media, women are often relegated to secondary roles, usually existing for little else than to serve as the romantic interest of male protagonists.

Many cishet Asian American men have noted how negative media portrayals of Asian men as sexually inadequate or perverse, socially awkward, and villainous have materially impacted their romantic lives. This phenomenon of life imitating art (and vice versa) is no less true for Asian American women. In fact, studies have indicated that sexual stereotypes of Asian American women often inform the frequent sexual and gender violence they face.

Politics

Historically, Asian American women have always been politically underrepresented. Historically, the vast majority of Asian American US senators and Congressional representatives have been men. Today, Congress may boast more Asian American women than men, but this is very recent change that neither reflects historical trends nor the state of Asian American representation at other levels of government.

At local and state levels, the gender gap in the Asian American community remains vast. Of the six Asian American governors in history, only one — Nikki Haley — has been a woman. In 2013, only 32 of 1,789 (or, less than 2%) of women serving in state legislatures nationwide were Asian American. Nationally, only about 1 in 4 state legislators are women, and in that same year, only one of America’s largest one hundred cities had an Asian American female mayor: Oakland’s former mayor Jean Quan.

Health

Gender disparities in the Asian America community are particularly visible in the realm of health and healthcare. Whereas about 15% of all Asian Americans did not have health insurance in 2013, the uninsured rate for Asian American women between the ages of 15 to 44 was more than one in five (or, more than 20%). Asian American women consequently have poorer access to preventative and primary healthcare for chronic, life-threatening conditions. For example, Asian American cisgender women are twice as likely as White cisgender women to die of pregnancy-related causes.

In addition to having reduced access to healthcare, Asian American women are also more likely to experience gender and sexual violence compared to Asian American men. Furthermore, Asian American women are severely impacted by a lack of focused studies. Although some data on this subject is available, many studies have been criticized for methodological flaws. For example, some studies have relied exclusively on telephone communication (even though not every survivor is willing to share their story with a stranger over the phone), while others have been conducted exclusively in English or have failed to provide adequate translation services in an appropriate variety of languages. The absence of reliable data on sexual assault in Asian American communities renders Asian American sexual assault survivors of all genders invisible, thereby limiting their ability to access services tailored to their unique experiences.

The few studies of sexual assault and domestic violence in Asian and Pacific Islander (API) communities are, however, quite damning. (Note: Asian American and API are not interchangeable terms, and API is used here and elsewhere only to reflect the methodology of specific studies.) One telephone survey of 800 API women found that close to 20% reported having been raped, physically assaulted, or stalked by an intimate partner in their lifetime. Another face-to- face interview study of 2000 Asian American women found that more than 10% reported experiencing some form of violence from an intimate partner in their lifetime. What is also clear even despite the limited data available on the subject, however, is that API women are the least likely to report sexual assault of any kind. This is especially true of immigrant women and women who lack English proficiency, suggesting that linguistic or other systemic barriers limit reporting. This conclusion is supported by the fact that US-born Asian women are twice as likely to report sexual violence compared to non-US-born Asian women.

Smaller studies on specific ethnic groups have revealed truly horrific trends as well. A 2011 study by the National Institute of Justice on Indian, Pakistani, and Filipina women found that more than 50% of each ethnic group interviewed had experienced sexual violence and stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime. A 2000 ATASK study found that over 25% of Korean, Cambodian, and Vietnamese residents of Massachusetts had grown up witnessing their fathers routinely physically abuse their mothers. A 1995 study of 211 Japanese immigrant and Japanese American women in Los Angeles County found that more than half had experienced physical violence and close to 30% had experienced sexual violence at the hands of an intimate partner. Finally, another study of Asians in the Houston and Dallas/Fort Worth Area found that over 20% of all Vietnamese respondents reported having experienced some form of intimate partner violence during the previous year, with 31% of the interviewed Dallas/Fort Worth Vietnamese men reporting at least one act of physical violence against their partner.

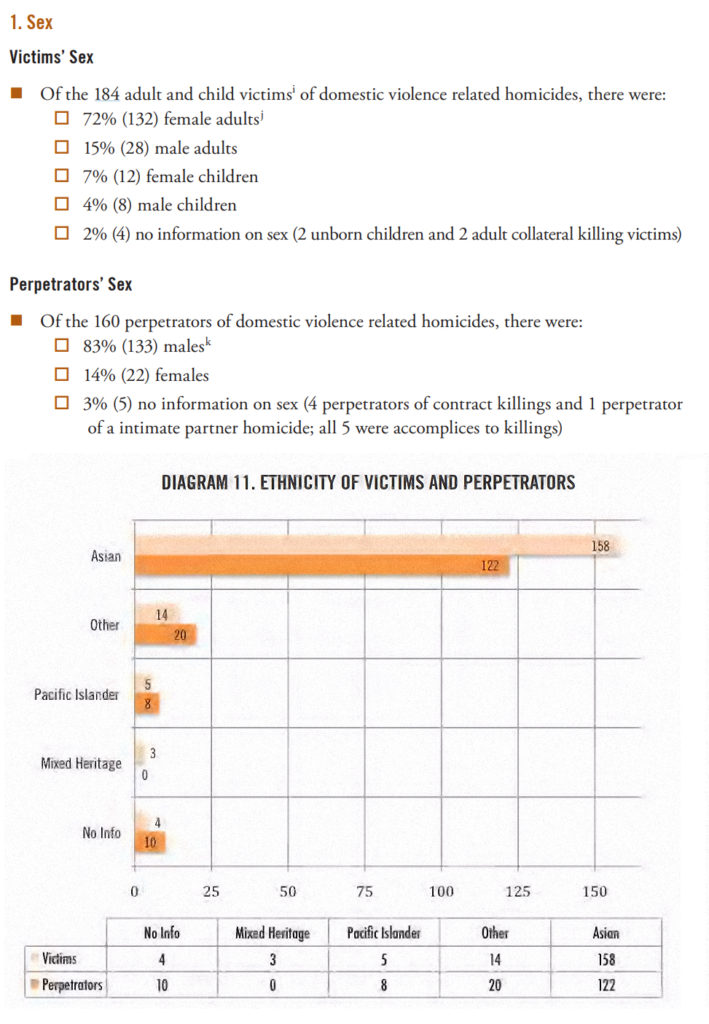

Homicide is among the leading causes of death for adult API women, with as many as half of those deaths possibly due to intimate partner violence. One six-year study of 160 fatal domestic violence cases involving API victims and perpetrators found that 78% of those killed were women and girls, whereas 20% of those killed were men and boys. The same study also found that 83% of the perpetrators of these homicides were men, versus 14% of perpetrators who were women. Of the 160 perpetrators of fatal intimate partner violence, 122 were of Asian descent.

As previously stated, there is a pressing need for more comprehensive and rigorous studies of sexual assault and domestic violence within API communities. While it is difficult to draw firm conclusions without comprehensive studies, a few trends nonetheless still clearly stand out that cannot be ignored:

- Domestic violence and sexual assault are underreported realities in API communities.

- The majority of perpetrators of domestic violence and sexual assault against API women are API men.

- API women’s experience of sexual assault and domestic violence is impacted by other circumstances such as immigration status, gender identity, sexual orientation, socioeconomic standing, English language proficiency, and incarceration.

Upon review of Asian American gender disparities in economics, political and media representation, and health, the reality of Asian American women’s oppression is incontrovertible. There is no evidence to support the notion of Asian American women possessing social privilege over Asian American men. The continued insistence on this baseless canard by some members of our communities is an attempt to derail the conversation on patriarchy, and comes at the steep expense of Asian American women.

MYTH 2: Asian feminists do not seriously resist White supremacy, and are largely focused instead on criticizing Asian American men.

There is simply no evidence to support this argument.

The modern Asian American Movement is largely built on the labor of Asian American feminists and women. Organizers like Cecilia Chung, Deepa Iyer, Tamara Ching, Grace Lee Boggs, Sharifa Alkhateeb, Helen Zia, Sarita Gupta, Yuri Kochiyama, Rasmea Odeh and Kshama Sawant have defined Asian American feminism and activism through their work. Scholars such as Gayatri Spivak, Tamara Nopper, Uma Narayan, Karen Ishizuka, Yen Le Espiritu, Merle Woo, Elaine Kim, Tithi Bhattacharya, Trinh T. Minh-ha, Celine Parrenas Shimizu, Nellie Wong, Sonia Shah, Ranjana Khanna, Lisa Lowe, Mitsuye Yamada and Mari Matsuda have produced tremendous scholarship and theory related to Asian Americans. From This Bridge Called My Back to Our Feet Walk the Sky, the political framework that underpins the modern Asian American Movement is a direct product of the work of Asian American feminists.

I could continue to offer names from both history and the present day to illustrate the grand work of Asian American feminists against White cispatriarchal imperialist capitalism, but in some way, this misses the point. For every luminary and visionary feminist whose name sits ready on our tongues, there are thousands – indeed, millions — of everyday Asian American women who have crossed oceans and continents, survived war, and labored extensively for the survival of our communities. The Asian American feminist struggle has a long and varied history, but one common thread that unites the many organizations and movements within this movement is a shared struggle against racism, patriarchy, and empire.

Part of that struggle entails naming misogyny in Asian American communities. Toxic gender logics which equate masculinity with domination position the bodies of women and femmes as proving grounds upon which masculinity is reproduced and certified. This kind of objectification endangers Asian American women and femmes and ultimately perpetuates the violence of White supremacist capitalism (which itself plays a significant role in the construction, normalization, and proliferation of toxic masculinities). Discussion and action against toxic masculinities in Asian American communities is therefore a necessary prerequisite for a liberatory politic—we cannot claim to fight for all of us without dismantling the violent gender regimes that imperil more than half of us.

The assertion that these kinds of criticisms are about denigrating Asian American cis men rather than protecting Asian American women and femmes depends upon an ahistorical and ignorant caricature of Asian American feminism which falls apart under even the most cursory of scrutiny. This is a reactionary position common to antifeminists in all communities, and ultimately serves to derail the conversation while demanding that feminists reinforce patriarchy by recentering men. Because everything women do is supposed to be in service of men, right?

MYTH 3: There is an epidemic of Asian women who refuse to date Asian men.

Many who endorse such claims cite articles such as this one, in which an East Asian American woman discusses why she will not date Asian men. This personal essay is a sad reflection on one person’s inability to let go of their internalized racism and assimilationist aspirations, even as they recognize these forces for what they are. The author also revealed that the post is a partially fictionalized account intended to serve as an outlet for the author to (poorly) process their thoughts on the subject.

Regardless of the aforementioned author’s intentions, her article is still used to promote the idea of an alleged “epidemic” of Asian women who refuse to date Asian men. Since one person’s article cannot provide sufficient evidence for such a claim, let’s look at this idea by the numbers.

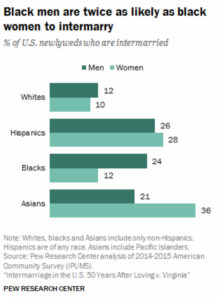

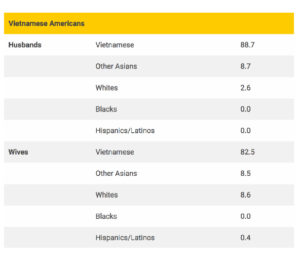

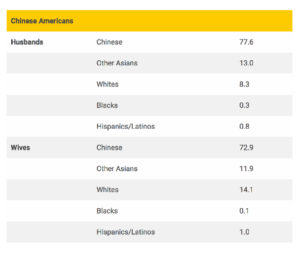

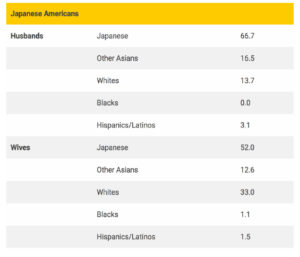

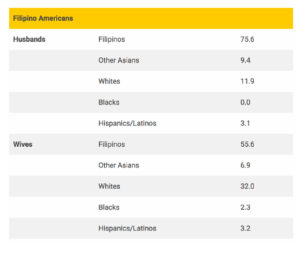

Many alarmist, antifeminist articles such as this one have focused on graphics (such as the one embedded below) released by the Pew Research Center that shows a gender gap in intermarriage rates between Asian American men and women.

What’s interesting to note is how these data are being interpreted. Many writers have concluded that these statistics are a sign of Asian American women’s collusion within the broader White supremacist structure, and further evidence of Asian women’s privilege relative to Asian men.

Yet such interpretations refuse to turn a critical eye to their own arguments. To begin, there is almost no examination of why Asian people’s ability or inability to marry White people should matter in the first place. Framing the conversation in this manner constructs a vision of liberation that is based entirely on White approval and acceptance. After all, if the problem is that more Asian American women are marrying White people than Asian American men, what is the solution? If Asian American men marry White people at the same rate as Asian American women, is the problem solved? Many antifeminists that seek to “reclaim” Asian American masculinity seem to think so.

This is contrary to the goals of an anticolonial and antiracist politic because it upholds the idea of White people as arbiters of belonging and desirability. By espousing a politics founded on aspirations for White approval and acceptance, writers who engage in this rhetoric are actively perpetuating a form of White supremacy.

Another flaw in Asian American antifeminist critiques of interracial marriage is the assumption that all Asian Americans who intermarry marry White people. This simply isn’t true; 3% of all interracial marriages in the US, for example, are between a Hispanic and Asian partner. Additionally, not everyone chooses to marry their long-term partner or the parent of their children, so marriage statistics alone cannot provide a complete picture of every Asian American person’s sexual and romantic choices. The fact that such arguments rely on this kind of erasure to erroneously suggest that a whopping 36% of Asian American women are marrying White men should speak volumes.

What is additionally often left out of the conversation is what these numbers mean and how things have changed. The fact remains that the majority of Asian women marry Asian men. Furthermore, Asian intramarriage (that is, the rate at which Asians marry partners within the Asian American community) is actually on the rise, and the intermarriage gap is shrinking. Furthermore, one must question the validity of translating these marriage statistics into sweeping generalities on the dating preferences of Asian women as a group. Even if we were to only focus on Asian women who marry White men, it would be almost impossible to conclude from these numbers alone that none of these Asian women would ever or have ever dated an Asian man.

It’s also interesting to look at the numbers in the context of other ethnic groups. Asian American men may have the lowest rates of intermarriage among men of color that this study accounts for, but the difference isn’t much. Black men have a three percent lead over Asian men and Hispanic men have a five-point lead over Asian men. Although there is a disparity, we should keep in mind that these differences amount to just a few percentage points.

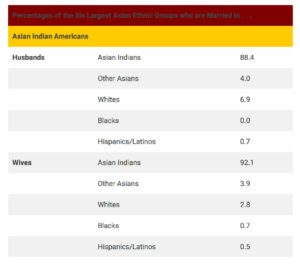

What’s additionally interesting is what happens when we disaggregate these data further. Intermarriage data disaggregated by data have been excluded from this writing for the sake of simplicity, , but you can read it here. The data I want to focus on are disaggregated to account for the six largest Asian national origin groups in the US.

Looking at the six largest Asian American national origin groups, it becomes clear that there are multiple factors informing Asian American intermarriage. Strikingly, more than 90% of Indian Americans and more than 80% of Chinese Americans – together representing the two largest Asian national subgroups in America — marry other Asian people. Meanwhile, the three subgroups with the highest intermarriage rates –Filipino, Korean, and Japanese American — also have the longest histories of US military occupation in their countries. Although further research is definitely needed, it would seem that military ties and colonial histories play a powerful role in influencing rates of Asian intermarriage.

Many inferences could be drawn from these data, but what is certain is that Asian intermarriage is the result of a variety of political, economic, and sociocultural factors that vary according to the specific histories of different Asian populations. The data further reveal that regardless of national origin, the majority of Asian American men and women marry other Asian people, and that both Asian men and women who marry a non-Asian person are most likely to marry a White person. The obsessive policing of Asian women’s dating choices is borne of statistical misrepresentation and dubious politics. It is one thing to talk about the costs of loving White people in a racist society and the relative, circumstantial privilege anyone can acquire through proximity (which itself can arise from any manner of relationships, whether professional, sexual, platonic, etc.), it is quite another to exclusively focus on Asian American women’s sexual and romantic choices as the litmus test of their politics. Sexual and romantic partners are not credentials to be displayed or scrutinized as determinants of authenticity or authority—the only metric of anyone’s integrity should be the actions they take in service of our struggle.

MYTH 4: Asian women’s attraction to White men is built on internalized racism.

I’m not going to debate the idea that internalized racism informs the politics of beauty and attraction. It’s a simple fact that most people alive on earth today are exposed to media images which promote Whiteness as the standard of beauty and Western modernity as the standard of sophistication and normativity. As a result, many people of color pursue proximity to Whiteness and Western modernity through political, socioeconomic, academic, cultural, and sexual means.

As previously discussed, the disaggregated data for the six largest Asian American subgroups clearly shows that both men and women who do not marry an Asian American person are most likely to marry a White person. The gender gap in intermarriage rates does not provide sufficient evidence to conclude that Asian men are somehow immune to (or less influenced by) White supremacist beauty politics than Asian women. There is no definitive metric through which people’s susceptibility to White supremacist beauty standards can be measured. Indeed, I would argue that the overall higher rate of intermarriage among Asian women says more about the preferences of White people than the preferences of any Asian person. Simply put, these data might suggest most White people don’t want to marry Asian men.

And, if so — so what?

What did White people ever do to deserve so much influence over our self-esteem as Asian men? Why are we so insistent upon winning the love of people who have chosen to despise us? Why aren’t we focusing more on the people who have never stopped loving us? Why are we spending so much time demanding that a system designed for our exclusion start including us? Why are we not instead building anti-patriarchal and anti-colonial masculinities as alternatives?

Part of such an alternative requires recognizing the bodily and sexual autonomy of all people. White supremacy has built vast industries, even economies, on the regulation and commodification of Asian women and women of color’s bodies, labor, and sexuality. The practice of shaming Asian women for intermarriage (while praising Asian men for the same behavior) serves no purpose other than to transfer patriarchal control from White men to Asian men. While some would describe such a change as a “reclamation,” it is impossible to “reclaim” something that was never yours in the first place.

MYTH 5: Asian feminists have no right to tell Asian men how to be men.

This last myth is a curious one, to say the least.

Many antifeminists attempt to discredit Asian feminist critiques of Asian and Asian American misogyny with a bio-essentialist argument for gender autonomy. The flaw in such an approach is that gender is not dictated by biology.

All gender identities are bound by the specific historical and sociocultural circumstances that contextualize their existence. Masculinity and femininity do not possess uniform qualities across space and time because they are performances with arbitrarily defined criteria. The same is true of nonbinary gender systems throughout history. Under racial capitalism, cisheteropatriarchy produces masculinities that define themselves through the subjugation of women, femmes, and all queer, trans, and nonbinary people. Such masculinities necessarily involve women and femmes because it is precisely through the violation of women and femmes’ autonomy and personhood that this masculinity is reproduced and validated. So long as women and femmes are implicated as victims of masculinity, masculinity will be the business of women and femmes.

All people deserve to express their sexuality and gender freely, but only insofar as they do not harm other people. Misogyny is a form of harm, and therefore it is not protected by cishet men’s right to gender and sexual autonomy. And, let us be clear: the notion that men are harmed by women’s sexual agency is misogyny. The idea that Asian American women’s loyalty to their race is measured by their support for Asian American men (which is itself determined by those same men) is misogyny. The idea that Asian American women are complicit in the oppression of Asian American men (when so many indicators would suggest the opposite) is misogyny.

All Asian American men, regardless of our individual history with women, must account for this misogyny. Not all of us have physically harmed women, but when we reinforce toxic masculinity we become complicit in the real violence it enacts upon Asian American women on a daily basis. Epistemic violence justifies physical violence, and we are all responsible for ending our complicity in both.

Ju-Hyun Park is a Gyopo essayist and storyteller whose writing can also be found at Juhyundred.com. You can also follow him on Twitter at @Hermit_Hwarang, and support him on Patreon here.

Learn more about Reappropriate’s guest contributor program and submit your own writing here.