Guest Contributor: Mark Tseng Putterman (@tsengputterman)

Asian American Twitter has been abuzz this week with news that Tilda Swinton singled out Margaret Cho to explain to her the backlash surrounding her whitewashed casting as “The Ancient One” in Dr. Strange. On a recent episode of Bobby Lee’s TigerBelly podcast, Cho described the odd email exchange with Swinton, who she had never met, explaining that it left her feeling like a “house Asian, like I’m her servant.”

While many commentators have rightfully jumped on Swinton’s behavior as another example of white people expecting people (especially women) of color to perform uncompensated intellectual and emotional labor, few have discussed how Cho’s coopting of the term “house Asian” represents a parallel trend of non-Black Asian Americans repurposing Black movements, analyses, and terminology for our own purposes.

The singular history of chattel slavery in the United States tells us that there were no “house Asians,” only “house n–ers.” While Cho placed her use of the term in the context of British imperialism, the phrase is clearly lifted from the context of American slavery, in which slave owners “elevated” the status of some slaves from working in the fields to the household. But Cho’s casual appropriation of the term reduced the history of slavery and its afterlives to a rhetorical device. To Black Americans, the commodification and eradication of Black bodies under slavery, Jim Crow, and mass incarceration is a terrifying inherited trauma, lived experience, and daily threat of violence. But Cho, like too many non-Black Asian Americans, chose to use antiblackness as a metaphor.

Given the hypervisibility of Blackness under white supremacy, many Asian Americans have found Black history and terminology useful as explanatory frameworks to visibilize our own histories of oppression. Cho’s “house Asian” remark leverages Black histories of oppression and the singular history of chattel slavery as a shortcut for explaining her own positioning as a Korean American woman asked to do unpaid labor for a white actress apparently entitled to her time. The shortcut works so well not because average Americans inherently pay more attention to Black issues than Asian American ones, but because of the work of generations of Black thinkers and activists who have pushed Black history and struggle at least marginally into the American mainstream. It’s a shortcut that erases Black struggle while using their histories as a metaphor to advance an Asian American agenda. But using antiblackness as a metaphor for Asian American struggle also limits the ways we talk about our own histories and movements. When we fail to employ nuance and specificity in our discussions of Asian American experiences with racism, we risk misdirecting Asian American anger away from the structures of white supremacy and towards Black communities—hurting all of us in the process.

When Cho calls upon Black history to explain her exchange with Swinton, or when Constance Wu insists on using the term “blackface” to describe Hollywood practices of yellowface because it’s “more evocative,” they model to non-Black Asian Americans that the only way to articulate our grievances is on the backs of Black thinkers. As Felix Huang described in a guest post for Reappropriate, we need a new language for expressing Asian American aggrievement, one with space for holding the singularity of Black oppression and the unique experiences of Asian Americans under white supremacy. Black analytical frameworks cannot be used as props for Asian American spokespeople to claim when useful and discard when they get in the way. Instead, they are a call for us to sharpen our own analytical frameworks, to work to push our own issues into the popular agenda, and to recognize that Asian American movements must take place in deep critical conversation with the mechanisms of antiblackness that are so foundational to systemic racism in the U.S.

When the only way we know how to articulate Asian American experiences with racism is by invoking antiblackness as metaphor, we imply that mainstream apathy towards Asian American political conditions is a result of unearned attention on Black communities. When we bemoan that people who would never wear blackface still think yellowface is acceptable, we are asking to shift antiracist attention away from Blackness and towards ourselves. When we complain that everyone knows about the history of slavery but far fewer know about Chinese and Indian coolie labor, we request that Black history be knocked down a peg or two in service of our own visibility.

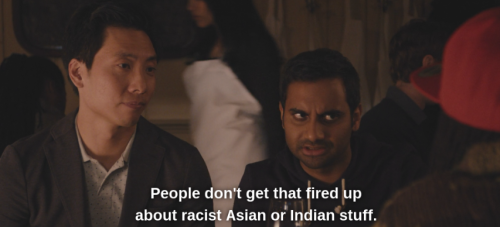

Aziz Ansari’s character falls into this trap on an episode of Master of None when he claims: “People don’t get that fired up about racist Asian or Indian stuff. I feel like you only risk starting a brouhaha if you say something bad about Black or gay people.” Like Ansari’s character, too often we let our frustrations with Asian American invisibility fester into a wound of antiblack resentment, failing to recognize the violence inherent to the Black hypervisibility so many Asian Americans seem to covet. These resentments have material consequences, as evidenced by the tens of thousands of Chinese Americans who marched to claims that former NYPD officer Peter Liang was a “sacrificial lamb” to the Black Lives Matter movement, or the anti-affirmative action advocates who claim that the policy pushes forward a Black agenda to the detriment of Asian American students. These narratives rely on a false view that Black political movements operate in opposition to Asian/Chinese American ones—that fixing political attention on the many manifestations of antiblackness somehow contributes to the invisibilization of Asian American issues.

In a brilliant scene in Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing, as a crowd of Black community members destroy a white-owned business in protest of a police murder, a Korean store owner attempts to diffuse the crowd from targeting his store next with a simple plea: “I’m black! You, me; same.” The scene resonates because beneath the simplistic audacity of the appeal, it articulates what so many Asian Americans have felt: a sense of connection to Black struggle as people of color living under white supremacy. Indeed, though one member of the crowd laughs off the Korean store owner’s claims to Blackness and another implores him to “open [his] eyes,” the crowd eventually turns away as one character remarks: “Leave the Korean alone…he’s alright.”

When non-Black Asian Americans can relate to Blackness as a political condition, it opens the door for solidarity movements that see Orientalism, imperialism, and xenophobia in relation to antiblackness. But too often, solidarity without specificity leads to erasure of those most marginalized. We must develop the language and frameworks to articulate what Spike Lee’s fictitious store owner could not. We are not Black. But when we tie our futures to the political conditions of Blackness, not as mere metaphor but as a moral demand for material justice, we create new pathways towards being seen in all our complexities and contradictions.

Mark Tseng Putterman (@tsengputterman) is thinking, organizing, and writing at the intersections of Asian American, Jewish, and mixed race identity and political movements. He is a 2016-2017 Visiting Scholar at the Asian/Pacific/American Institute at NYU.

This piece was informed in part by engaging with work by Shanice Brim (@ShaniceBrim), Felix Huang (@Brkn_Yllw_Lns), Jahlani Smothers-Pugh, and @dtwps. I encourage all readers to follow their critical work!

Learn more about Reappropriate’s guest contributor program and submit your own writing here.

Update (12/20/2016): Several readers have raised concerns that the original version of this post used the word “crutch” in a negative and ableist way. The author has elected to revise this post and to remove the problematic usage of the term.