Guest Contributor: Dr. Keith Chan

This article appears as a response to a recent guest writing by Mark Tseng Putterman that appeared on Reappropriate last week, “Against Antiblackness as Metaphor.”

Recently, Mark Tseng Putterman wrote “Against Antiblackness as Metaphor” as a discussion of actor and comedian Margaret Cho’s use of the phrase “House Asian” in an email exchange with fellow actor Tilda Swinton. Cho and Swinton had been emailing in relation to months of controversy over Swinton’s casting as The Ancient One in Marvel’s Dr. Strange, wherein a traditionally male, Tibetan comic book character was rewritten as a Celtic woman to enable Swinton’s portrayal; many Asian Americans had criticized Swinton’s casting as the latest example of Hollywood white-washing of Asian American roles. Earlier this month, Cho weighed in on the controversy in a podcast by revealing a private email exchange between herself and Swinton, wherein Cho described feeling as if she had been put by Swinton into the politically dubious role of a “House Asian”. While many have since focused on Swinton’s methods and motives in approaching Cho in this exchange, Putterman offered a slightly different take: he wrote to criticize Cho’s choice to use the phrase “House Asian” in her emails with Swinton. Specifically, Putterman suggested that Cho, like many Asian Americans, should reconsider our use of metaphors of Blackness to legitimize racial justice issues associated with the Asian American community, and that our continued use of such tactics undermine solidarity efforts between the Black and Asian American community.

I believe Putterman’s article raised many insightful points, and offered a fair caution against the appropriation of race identity, especially in the case of Asian Americans seeking visibility and acknowledgment of the discrimination we face. Cho’s use of the term “House Asian” during her email exchange with fellow actor Tilda Swinton is indeed controversial.

Based on his writing, I believe it was Malcolm X who coined the phrases “House Negro” vs. “Field Negro” to highlight the relative instability of the plight of all subjugated Black people. Along those lines, Ture and Hamilton’s work, Black Power, also assigned a commonality of experience of subjugation for populations of color across the globe, and coined the term “Third World.” This latter term has fallen out of favor since the 1990’s. Cho’s use of “House Asian” misses many of these nuances, and runs the danger of advancing an agenda where all experiences of discrimination, based on race or otherwise, can be viewed as equal.

Clearly, they are not.

As Putterman pointed out, the use of anti-blackness as a metaphor by Asian Americans, or by any other marginalized group as an explanatory framework, is a shortcut that threatens to erase Black struggles and its history. Furthermore, the dangerous logical corollary which follows is that there is an equality of oppressions, regardless of race. This color-blind paradigm fails to acknowledge the entrenched legacy of racism, and that it continues to be a social problem rooted in anti-blackness. The glass ceiling still exists for Asians, but between 1940 and 1970, the US became less racist towards Asian Americans, and we are now getting close to equal pay for equal work, compared to whites. Education improves incomes for everyone, and having a college degree helps to close the wage gap for Blacks. However, modern racism works subtly, and looking upstream from college graduation, we find enormous differences in opportunities for education, treatment by law enforcement, and exposure to violence due to structural anti-blackness. As Asian Americans, we experience institutionalized racism, but are similarly privileged as whites to the safety of our personhood when we encounter police officers. We have to acknowledge our own privilege in order to have any real, critical discussions on claims of neutrality, fairness, equality, and racism.

Should Cho then acknowledge her privilege here? I believe the answer is yes. As a fellow Asian American, I believe Cho’s experiences of discrimination are very real. However, I also believe those experiences are couched in the relatively successful world where she resides — or, at least right now in her career. Cho has worked hard for the position of prominence she now enjoys, but she has likely also received less than she deserved. There is also an intersection of gender that emerges with consideration of Cho’s professional trajectory, especially in the very sexist world of entertainment and stand-up comedy. In the past, I have heard her highlight her experiences of discrimination specifically as an Asian woman in her comedy routines. I find them funny because they come from a very authentic place; many Asian Americans can likely relate to her account of her experiences. But, this does not erase the fact that Cho has benefited from a certain privilege. Cho, in the midst of her oppression, has an outlet for her frustrations, when Swinton was looking to be exculpated as a well-meaning though not particularly well-informed white person. Cho’s outlet is part of her hard-earned fame, but the artistic freedom she enjoys, even in how she disclosed her exchange with Swinton, is a privilege that most other subjugated persons, regardless of race, simply do not have.

Cho entered into an explicit agreement of confidentiality before sharing her exchange with Swinton to the world. She can do that, as an entertainer and a comic, and more or less still get away with it. If Swinton had an open conversation with her, or demanded her approval as a token Asian in a public forum, then Cho’s actions in sharing this conversation would not be ethically questionable. Cho’s actions here are on the fringe of what is acceptable, moral behavior. Cho cannot fairly represent herself as a victim, and Swinton has valid cause to feel aggrieved. Furthermore, Cho’s actions, and so far the lack of any real consequences, is indication of her position of privilege in society.

There are points in Putterman’s article that I do not agree with. The use of the term “House Asian,” at least in my reading, does not imply anti-blackness. Putterman is astute in pointing out that when Asians co-opt the language of Black power and its analytical frameworks, we delegitimize our own histories and run the risk of becoming exploitive to the Black experience. The language we as Asian Americans use must reflect the changing dynamics of race, with authenticity and purposive mindfulness to power, privilege, and subjugation in the historical context of color. Race identity of all folks of color has inevitably evolved, and Asian Americans perhaps more so than any other race group in the late 20th and early 21st century. There is an intersectionality of class, gender, cultural variations and immigration status that has further complicated the race narrative. In truth, though, the existence of intersectionality is not new, for Asians or Blacks. Malcolm X’s “House” vs “Field” metaphor is also inherently imperfect, and historically so, because a clear delineation never truly existed. Blacks who worked in the fields and in the house enjoyed varying degrees of status and privilege, but it was always in relation to a white master. For Asians, our own changing status which evolved from a race identity as a despised minority to a model minority has also always existed in relation to white power structures. Cho’s usage of “House Asian” in response to Swinton applies an imperfect metaphor which fails to authentically represent the Asian American experience. It does, however, work in making critically transparent the role that Asian Americans play to whites as a foil to their stories. Swinton wanted Cho to understand that she was not a racist, and sought out dispensation for her own privilege. Ironically, in this story, Cho is the Ancient One to Swinton’s Dr. Strange.

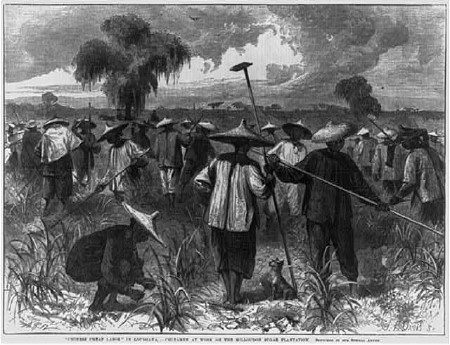

Nonetheless, I agree that Cho’s application of this metaphor to the experiences of Asian Americans is problematic. Asian Americans toiled in fields for roughly a century in Hawaii and California, but our race identity has always existed in close juxtaposition to our immigrant identity. In our modern history of immigration, and in the days to come under a new administration, perhaps the best metaphor might juxtapose the “Fenced-in” vs. the “Fenced-out.” Our current political climate has become increasingly perilous for immigrants, and talk of a physical fence belies the ideological fence that has been erected in the American consciousness. The “Fenced-in” vs. “Fenced-out” metaphor reflects the political identity that we as Asian Americans now have to navigate. The Asians who are recent immigrants, the elderly, poor, or undocumented are “Fenced-out” from proximity to white privilege. The “Fenced-in” Asians are expected to conform to the narratives of white people, and when necessary, assuage white guilt when white people are confronted with their own racism. Similar to the “House Negro” and “Field Negro” metaphor, no matter which side of the fence we sit on, we as Asians continue to exist dangerously at the mercy of white, oppressive institutions. Our job is to dismantle these institutions and tear down that fence, not to reinforce them through our bids to be have privileges closer to the white man.

As Asian Americans, our understanding of privilege and subjugation must evolve. We can – and should – develop better metaphors that are authentic to our own histories, and that honor the experiences of others who fought the good fight before us. In so doing, we move the cause forward in collaboration with true social justice.

Keith Chan is an Assistant Professor in Social Welfare, at the University at Albany SUNY. Dr. Chan has published his research on health disparities for Asian Americans, and also on issues of race and discrimination.

Learn more about Reappropriate’s guest contributor program and submit your own writing here.