There is a scene in And The Band Played On where Matthew Modine’s character explains the origins of the phrase “The Butchers’ Bill”: a phrase coined by British Admiral Lord Nelson when asking for the daily casualty reports of soldiers lost in the Napoleonic wars. In the film, Modine’s character creates his own Butchers’ Bill for the AIDS epidemic, and it remains one of pop culture’s most poignant visual reminders of the devastating cost of the disease in human lives.

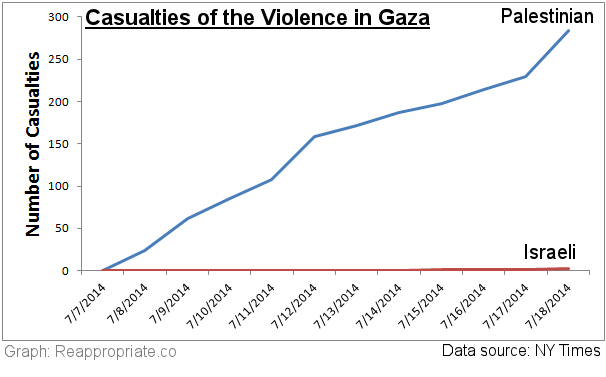

The Butchers’ Bill in the ongoing violence on the Gaza Strip is equally heart-breaking. In less than two weeks time, Israel has launched airstrikes against Palestinian residents of Gaza targeting over 1500 sites; Hamas has also launched over a thousand rockets into Israel that have all been largely ineffective. As of today, the Butchers’ Bill for Palestinian residents of Gaza nears 350 after 11 days of fighting, nearly fifty of those dying in the last 72 hours at the hands of invading Israeli ground troops. The United Nations estimates that three-fourths of Palestinians killed in Gaza by Israeli offensive actions this month were non-militants, and approximately 50 — a third of them killed since Thursday — have been children. An additional 2000 Palestinians have sustained serious injuries in the attacks. The UN reports that yesterday the number of Palestinians displaced by the violence has nearly doubled to 40,000 — all seeking refugee status in one of 34 UN shelters.

There are no words to describe the rage and grief I feel in watching this senseless killing unfold. But the price of my silence — and the silence of too many of us in America — is also far too high.

On Wednesday, reporters and bystanders watched in shock and horror as an Israeli gunship brutally slaughtered four young Palestinian children (none older than eleven) on an otherwise deserted Gaza beach. After an initial strike, the Israeli planes returned to chase and gun down the four young boys — all cousins — as they ran screaming for their lives. Just 24 hours later, seven children were shot — four of them fatally — by an Israeli naval gunboat while they were playing soccer on a Gaza rooftop.

In the last two weeks, four Israeli have lost their lives.

Too many of us are allowed by the comforts of distance to pretend that what is happening in the Gaza Strip right now does not affect us. That distance comes in many forms: geographic distance, cultural distance, religious distance, racial distance, and linguistic distance. That distance gives shelter to our assertion that what is happening to Gaza is not happening to us. It gives shelter to our rationalizations and our justifications. It gives shelter to our dehumanization of the Palestinian people. It gives shelter to our silence.

That distance is also a lie and an illusion.

David Palumbo-Liu writes about how violence in Israel-Palestine is a matter of American studies, particularly in light of our country’s hand in shaping the conflict. He and many other writers have noted the US State Department’s stance in defense of Israeli airstrikes targeting Palestinian civilians; President Obama defended that stance to Muslim American guests at the White House’s annual iftar dinner. Like it or not, America is involved in what is happening in Israel-Palestine.

Let me be clear: most of us do not know what it is like to live as a Palestinian in the Gaza Strip. As a Canadian-born (East) Asian American, I do not know what it is like to live as an occupied people in my own Holy Land. I do not know what it is like to live under constant threat of overwhelming military violence and death. I do not know what it is like to find myself staring down the barrel of an assault rifle, or be targeted by the sophisticated weapons mounted on a gunship or an F-16. I also do not know what it is like to be brown and Muslim, and to have these two simple facts of my being cast me as a villain and a terrorist.

But, what is happening in Gaza still touches me on a fundamental level.

For so many Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, the plight of colonized people is familiar and deeply personal. Most Asian and Pacific Islander countries still bear the scars of both military and cultural occupation, whether by Western powers and/or by other Asian nations; some of our lands still remain occupied to this day. Most of us in the AAPI diaspora share a blood memory of the violence that is wrought by occupying forces against indigenous peoples, and the political, cultural and militaristic tools that have been used in the exploitation of our lands and our people.

Most of us can still identify the after-shocks of colonialism on the course of our lives. Some of us share family memories of the atrocities of war that came with revolution against occupying forces. Some of us are in America as refugees fleeing the violence of war. As Americans and/or descendant of certain Asian nations, many of us are complicit as colonizers; some of us also still live as colonized peoples today, and for many of us that fight against the colonizers rages on.

It is true that I am not Muslim and I am not Palestinian. I also do not need to share in those identities to see the connection between their struggles and my own political narratives. I do not need to share in those identities to recognize the humanity of the Palestinian people in the Gaza Strip, and to lament their devastating and senseless slaughter. I do not need to share in those identities to stand in solidarity.

I need only be human.

I do not know how to end the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. All I know is that this bloodshed has got to end.

Millions of activists around the world — including protesters in many Asian countries — have taken up the cause of the Palestinian people fighting against occupying Israeli forces. It is time for Asian Americans to join our voices to this expanding international chorus of outrage.It is time for us — as AAPI and as moral humans — to take a vocal stand in solidarity with Palestinian people, and all our Muslim American brothers and sisters in the States. We can no longer allow others to pay the price for our silence; for now we are again reminded that the price of our silence is too high.

Acknowledgement: Many thanks to Tanzila Ahmed (@tazzystar) for inspiring, and providing many resources, in the writing of this article.

Correction: An earlier version of this post had Tanzila’s name misspelled. My apologies to her, and thank you to reader B.G. for the correction.