By Guest Contributor: Mia Ives-Rublee

I spent my childhood hearing from white adults about the immoralities of Asians. I was told about how strict Asian parents were and that Koreans were too patriarchal. People would go out of their way to show me negative news articles that talked about Asians in a bad light. They insisted I was lucky to not have parents like that.

The continual feed of negative attitudes rubbed me the wrong way, making me want to be less and less connected to the Asian American community. As a child, I ascribed to the colorblind philosophy that adults pushed upon me. Oftentimes, I forgot I was Asian unless someone pointed out some physical difference I had.

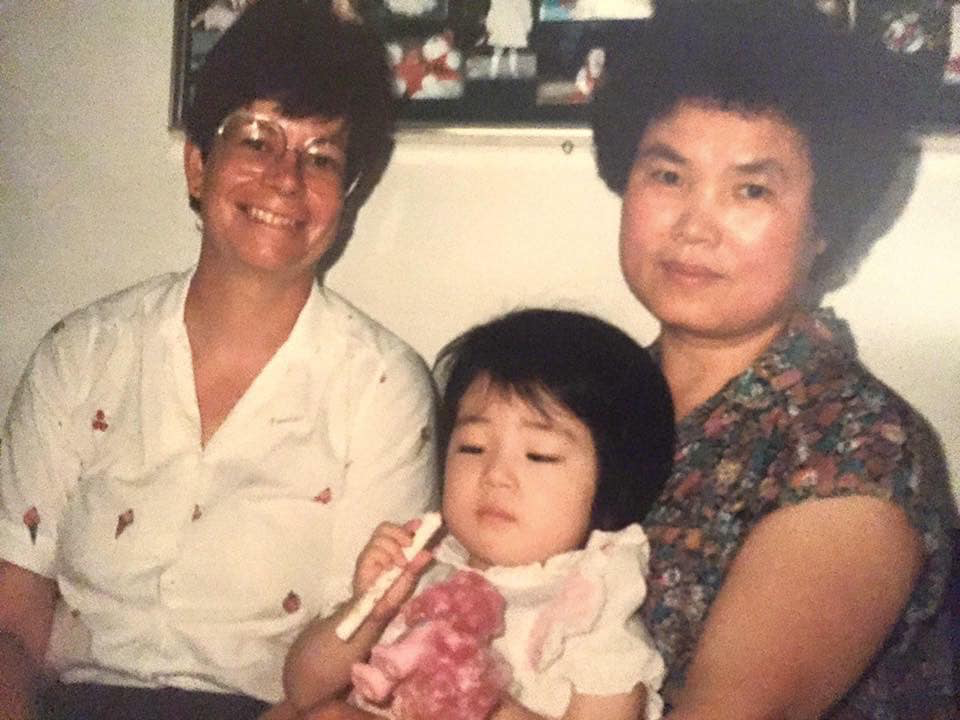

My experience is hardly unique. More than 200,000 people in the United States were adopted from Asian countries, a majority from South Korea. A study published in 2017 showed adoptive parents of transracial adoptees engaged less and less culturally with their children as they aged and that very little was done to engage them around racism. In fact, many adoptees don’t tell their parents about the racism they experience. A study by Sara Duncan-Morgan showed that a majority of respondents who were transracial adoptees avoided talking to their parents about the racism they faced.

With few resources to deal with my situation, I felt absolutely isolated and distrustful. I knew very few adoptees and had no adults that could explain what I was experiencing. It wasn’t until college that I reconnected with someone from the Asian American community. Her name was Catherine and she was, what I like to call, one of my Asian American mentors. I remember we attended a retreat together. One evening, we were told to create a skit. As we began to plan, Catherine started talking about the racism she and other Asian Americans experienced. That night, something finally clicked for me. The discomfort that I felt from being teased and othered had a name: racism. Catherine became my safety line into a community I had felt excluded from.

These days I am a long way from the isolated youth who hated being different. I now advocate for AAPI communities, working on policies that directly affect us. Two winters ago, I got the privilege to work at an AAPI organization turning out the AAPI vote in Georgia during the special election. I was also honored to be appointed as a commissioner for the President’s Advisory Committee on Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islanders.

Yet I continue to be frustrated at how invisible transracial adoptees remain in the community, even as many of us find our way back to the community as adults. It is as if our own existence is a blemish, a reminder of a colonized past and the failures of our elders to protect and care for us. I continue to fight for visibility and broader inclusion, including co-founding Adoptee Voices Rising, an organization building towards a transracial adoptee bill of rights. It’s important to fully acknowledge, particularly during Asian American/Pacific Islander Heritage Month, that Asian American transracial adoptees are part of Asian American history. No matter what people tell us, we are Asian American enough.

Mia Ives-Rublee is a disabled transracial adoptee who has dedicated her life’s work to civil rights activism. She began her journey as an adapted athlete, competing internationally in track, road racing, fencing, and crossfit. She obtained her Master’s in Social Work at UNC Chapel Hill and began working with disabled people to help them find work and independence in their communities at the NC Division of Vocational Rehabilitation Services. Mia is best known for founding the Women’s March Disability Caucus and organizing the original Women’s March on Washington in 2017. She has worked with numerous progressive organizations on disability justice and inclusion. As a public speaker, Mia advocates on the national stage for the rights of disabled people, immigrants, and other marginalized communities.