By Guest Contributor: Billy Yates

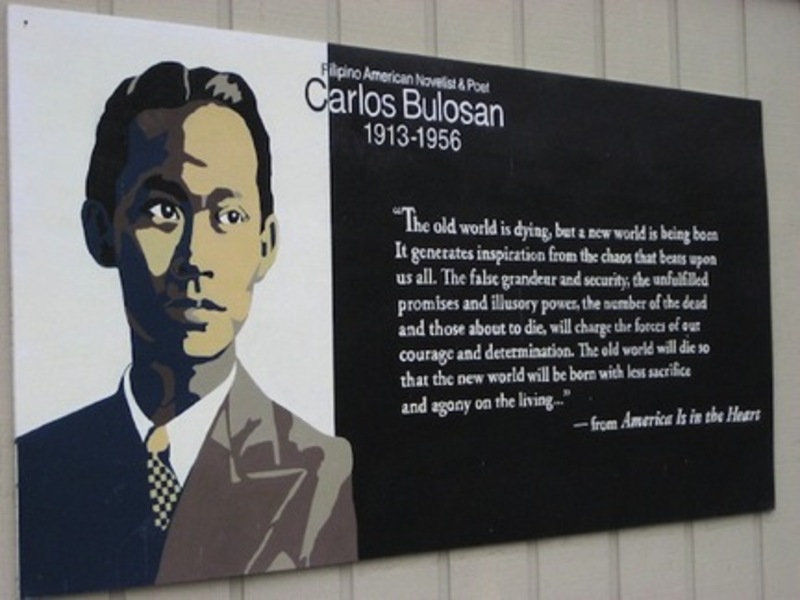

Editor’s Note: Carlos Bulosan’s birthday was November 24.

The ghost of Carlos Bulosan lives in the Los Angeles Public Library. I have no way to prove it, but I trust in coincidence.

In 2018, the New Americans Initiative center opened, offering citizenship and ESL classes along with multilingual resources for immigrants from the over 140 countries that call LA home. It was launched on the first floor’s International Languages Department, where many enter with hopes of constructing their own America Dream; it is one of the floors that radical Filipino writer, organizer, and dreamer Carlos Bulosan frequented in the 1930’s and 1940’s. Here, Bulosan explored the world’s stories through books, absorbing authors that would influence his own reflections of the immigrant experience at the peak of the Great Depression. Rereading a worn copy of Bulosan’s America is in the Heart, sitting next to a stack of N-400 citizenship applications and multilingual Know Your Rights! Pamphlets, I am torn by the prophetic poignancy of it all. In a time when official policy is to “Make America Great Again,” Bulosan begs the question: What is America, and who is it great for?

In a time when official policy is to “Make America Great Again,” Bulosan begs the question: What is America, and who is it great for?

“Books invite all; they constrain none.” These words are engraved on the Hope Street tunnel entrance to the library – the one Bulosan would have used. Whenever I pass them, these words never fail to prod a moment’s pause, silencing sounds of traffic. This building is many things: free, public, an all-you-can-eat-buffet of knowledge, and most importantly it is the first place many turn to in times of need in the city of Lost Angels. My paternal grandpa taught himself to read here as an orphan, at the same time that Bulosan would have found abundant company in the warm and well-lit rooms of the library that attracted great crowds of the unemployed during the Depression. After organizing workers from Alaska down the West Coast, Bulosan found a home in LA. His other home was the library. He spent days, “waiting for the dark to hide my dirty clothes” before emerging into night onto Temple or Alameda streets to visit the pool halls and clubs where Filipinos men congregated after work, or home to digest the many authors he read at the library. Writer Alfonso Santos met Bulosan in the library where their conversations turned to “the rising power of the working class,” the theme Bulosan transformed in his experiences as a worker and immigrant into literature, always intent on elevating “working people.” The original design of the library called for a literate building, integrating sculpture, art and text with the mission to uplift and inspire. While he never attended college, Bulosan accepted and committed to the open invitation from the library that was offered every day above the tunnel entrance. Bulosan was determined to leave his mark as an immigrant in search of the American dream. As a Filipino, he couldn’t have arrived at a darker time.

To arrive in America one year after the stock market crash of 1929 was to enter into an historical turning point for the country. After the economic collapse, farmers in California increasingly saw the influx of Filipinos as a threat to their livelihood. The white, male economic insecurity gave rise to roaming bands of organized vigilantes driven by the self-appointed mission of rounding up and expelling Filipinos from the expanding towns of the San Joaquin Valley. In equal (if not greater) ferocity was the intensification of imagined ‘sexual rivalry’ between Filipinos and white males. Of the 42,500 Filipino Americans counted in the 1930 census, only 2,500 were women. This profound gender imbalance led to an inevitable coupling between Filipino men and white women, a relationship made illegal under anti-miscegenation laws that forbid marrying between whites and “Negroes, Mongolians, Mulattos and Malays”. On January 10, 1930 in Watsonville, California, an anti-Filipino resolution was adopted to discourage the hiring of Filipino workers, drawing upon a rationale of highly-charged sexual undertones. The author of the resolution, Judge D.W. Rohrback, was frightened by “the prospect of Filipino-white marriages” anticipating that California would be overrun by “half-breeds.” His fear was shared by founder of Cal State Sacramento, C.M. Goethe who published in Current History Vol. 34 that “the resulting hybrid is almost invariably undesirable,” and like Rohrback believed that the “ever increasing brood of children of Filipino coolie fathers and low-grade white mothers may in time constitute a serious social burden” (If only they lived to see the immense social burden ‘stirred’ by such “‘half-Filipinos”as Enrique Iglesias, Gabrielle Wilson, Nicole Sherzinger and Bruno Mars for people worldwide).

Increasing tension over Filipinos’ relations with white women after the passing of the resolution in Watsonville escalated into violence. A mob of 500 hundred white men rampaged the Filipino community, burning and looting Filipino farmers’ bunkhouses and clubs. A stray bullet ended the life of Fermin Tuvera, a farmworker shot while sleeping in a bunkhouse. His martyred body was sent to Manila as a rallying cry against racial hatred and colonialism. The terrorism lasted 5 days in Watsonville and also spread to other cities: Santa Rosa, San Francisco and Stockton. On January 29th 1930, the Stockton Filipino Center was bombed with dynamite while around 40 people, including women and children, slept inside.

In contrast to this violence, the Central Library – a space Bulosan might have considered a second home – was a haven of safety and enlightenment, a galaxy of languages and text. One can travel the world in a book. My mom learned about America reading Little House on the Prairie, the settler adventures of a white family living out on the plains of frontier America. ‘Did they really have a schoolhouse that small?,’ she asked herself from her home in Paranaque, the seething southward borough of rainbow sprawl located 6 miles south of Ninoy Aquino airport, where she would eventually leave for the US. A relative’s journey to meet distant lands is part of almost every family’s story in the Philippines, a country where the prime export is people. 500 years of colonialism – first the Spaniards before the arrival of the far-more-efficient Americans – has resulted in a country where the practice of exploiting labor has been long refined. Filipinos today are everywhere – from the oil rigs of Saudi Arabia to the streets of Hong Kong to the hospital in the city you live.

Bulosan did not merely write about the unresolved, unsettling contradictions of life in America. PC Morante comments that Bulosan himself “lived with daily accounts of violence, exploitation and discrimination against Filipinos,” but also “accounts of resistance, attempts to organize and even interracial love.” Regarding Bulosan’s inspiration for the novel, friend and biographer PC Morante explains:

“[W]e both knew for facts many brutal incidents which had happened to others — Filipinos, Mexicans, Blacks and Whites — especially striking workers in various fields who were savagely abused or tortured by the heartless minions of power or lackeys of the law. Carlos’s heart bled for them, cried for them. That is why he did not hesitate to claim the barbarities done to them — to all underdogs, to all the oppressed to all the poor fighters against abuses by the rich and powerful — as his own.”

Bulosan’s motivation was rooted in his own experience but energized and fueled by compassion. Organizing across racial lines – an experience that ranged from defiant solidarity to violent betrayal – Bulosan’s America is in the Heart becomes what Dr. Susan Evangelista describes as “not a personal matter, but a stage in history, a part of a historical struggle towards liberation” for all peoples.

Bulosan’s motivation was rooted in his own experience but energized and fueled by compassion. Organizing across racial lines – an experience that ranged from defiant solidarity to violent betrayal – Bulosan’s America is in the Heart becomes what Dr. Susan Evangelista describes as “not a personal matter, but a stage in history, a part of a historical struggle towards liberation” for all peoples.

Bulosan’s need to analyze America came in a comparable way to writer James Baldwin, who stated in Notes of a Native Son: “I love America more than any other country in this world, and, exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” Bulosan, who always considered himself a poet foremost, “became convinced that it was the duty of the artist to trace the origin of the disease that was festering American life.” Just as Baldwin did not hide his love for America while rhetorically dismantling its racist roots and false mythologies, Bulosan finds in the trenches of resistance a beautiful, radically reimagined ‘America that could be,’ one where words such as “freedom” and “equality” become tangible, carrying weight and definition to all. His identification with the struggle allowed him to feel that he “had found a place in America” elevating and writing working people’s stories. “The fight to hold on to this feeling convinced me that I was becoming a part of living America” he writes. He found his role, as a writer, an organizer and a Filipino in a country that promised much but delivered so little. Amidst the turmoil of the labor movement, Bulosan proclaimed that the “the most decisive move that the writer could make was to take his stand with the workers.” It was the stories of working immigrants that Bulosan made prominent.

While picking apples and processing the differences of an America that fell far short from the promise he was taught in the colonial Philippines, Bulosan begins “to ask if this was the real America – and if it was, why did I come?” I am reminded of my mom’s loneliest nights after finishing her shifts at Chick-Fil-A in the Del Amo Mall on Hawthorne Blvd, her first months in the US in 1986. She arrived in LA without any documents and an ocean between her two young children left in the Philippines. Fear of deportation hounded her nightly with paranoia. Conversations with herself lived in her head: Can I just go home? What will I have to show of my American journey? She started attending daily mass again. She prayed against the solemn refrain that repeated itself in her head everyday: If I die here will anyone even know?

These prayers are undeniably loud across every state in the union in 2020. To read Bulosan today is to examine a history strategically obscured in favor of propagating an American Myth built to undermine solidarity and our collective identification. Immigrant parents praise the potential of their children’s reach, wishing them to seize opportunities for a better life in the future. We are told foundations for success are laid by hard work, not by dwelling on oppression or a disconnected history. Immigrants come to this country fighting from day one, why look back? Why read literature or history? The answer is in the in-between.

The generation gap, explains Audre Lorde, is a tool used by every repressive society. To read Bulosan today is to do the necessary work to bridge that gap, to learn our story and analyze the present conditions of society in such light. In doing so we recognize that present conditions are the latest reincarnation of cyclical symptoms of a country built on exploiting labor for profit and power. In the words of E. San Juan Jr, “We must use Bulosan, that’s what he lived for.” Literature is art and history recorded, entertaining and weaponized for times like these — times when xenophobia and racism are openly wielded to maintain division. We exist today as either victims or witnesses to an upsurge in hate against those that do not fit into what it means to be American. The attack is not new, but for many of our generation the latest assault on immigrants feels unprecedented. For Filipino Americans, we live an ocean of anxiety that bridges brutal authoritarianism between two dictators, elected by some of our very own aunties on both sides of the Pacific.

Maybe the question is not who, but what does it mean to be an American? What does it mean to take the hallowed promises of “freedom” and “equality” to task and transform them into collective action? What would Bulosan see today? Some things don’t change. In 2020, Filipinos stand on the frontline of a global pandemic. They are essential workers across the globe, and like others whose livelihood has been regulated to sacrificial hero status, they pay the price of the historical legacy of discrimination Bulosan described. While Filipinos make up 4% of the nurses in the US, they account for a sobering 31.5% of COVID deaths among nurses.

Yet, Bulosan would also find, with pride, that other things haven’t changed either. From the legacy of farm and cannery workers on the West Coast that broke ground organizing across colorlines in his time, the fight continues. Whether serving as caregivers in Taiwan, nurses in New York, or seafarers keeping the international shipping industry running, Filipinos are also the frontline of organizing, breaking ethnic barriers, and fighting for not only their rights but for the rights of all workers.

The challenge Bulosan leaves us is to read and act and live and write in empathy with humanity, immigrant, non-immigrant, black and native, to imagine and organize not just another America, but another world, in fulfillment of his prophecy in America is in the Heart

The challenge Bulosan leaves us is to read and act and live and write in empathy with humanity, immigrant, non-immigrant, black and native, to imagine and organize not just another America, but another world, in fulfillment of his prophecy in America is in the Heart:

“The old world is dying, but a new world is being born. It generates the inspiration from the chaos that beats upon us all. The false grandeur and security, the unfulfilled promises and illusory power, the number of the dead and those about to die, will charge the forces of our courage and determination. The old world will die so that the new world will be born with less sacrifice and agony on the living.”

Without a doubt we are living in bleak times. But we are also fighting back. Protests flood the streets of America daily demanding racial justice, daily. Tenants are organizing. Nurses across the country, often led by Filipinos, are going on strike for their safety, dignity and respect in hospitals across the country during a pandemic. Maybe Bulosan’s ghost does not live in the Los Angeles Library. Maybe it is not a ghost, but his spirit that I feel, and it is in the bravery of those that continue to fight that I begin to see the America he held so close to heart.

Billy lives in Los Angeles. He loves the library.

Learn more about Reappropriate’s guest writing program and submit your work here.