For this year’s Asian American & Pacific Islander Heritage Month (#APAHM2014), I will be celebrating by writing multiple pieces throughout May tackling a variety of issues relevant to Asian & Pacific Islander Americana. Please continue to check back for more, and participate in the conversation in the comments, on Facebook, and through Twitter (@Reappropriate)!

As we mark the start of 2014’s Asian American & Pacific Islander Heritage Month this May, one of the central questions we might find ourselves asking is: what is Asian & Pacific Islander Americana? Who is part of this community? Who are we?

Our communal identity crisis has plagued us since the passage of the 1965 Immigration Act sparked the massive and diverse second wave of Asian immigration, and when the idea of a pan-ethnic “Asian American Movement” first took hold. The term “Asian American” of the 1960’s eventually gave way to “Asian Pacific American” (APA) to reflect the narratives of Pacific Islanders; today, several alternative terms are also in use, including “Asian American & Pacific Islander” (AAPI, my term of preference), “Asian & Pacific Islander American” (APIA), or “Asian American, Native Hawaiian & Pacific Islander” (AANHPI).

This ever-evolving nomenclature reflects the seeming impossibility of ever finding a term that will be fully satisfying to the widely disparate ethnic identities that find ourselves sharing space under this pan-ethnic AAPI umbrella. When we differ so widely not just in our individual ethnic histories and heritage, but also in our very physical appearances, the languages that we speak, or the religions that we practice, it is not unreasonable to wonder how or why we should continue to find our political destinies linked together.

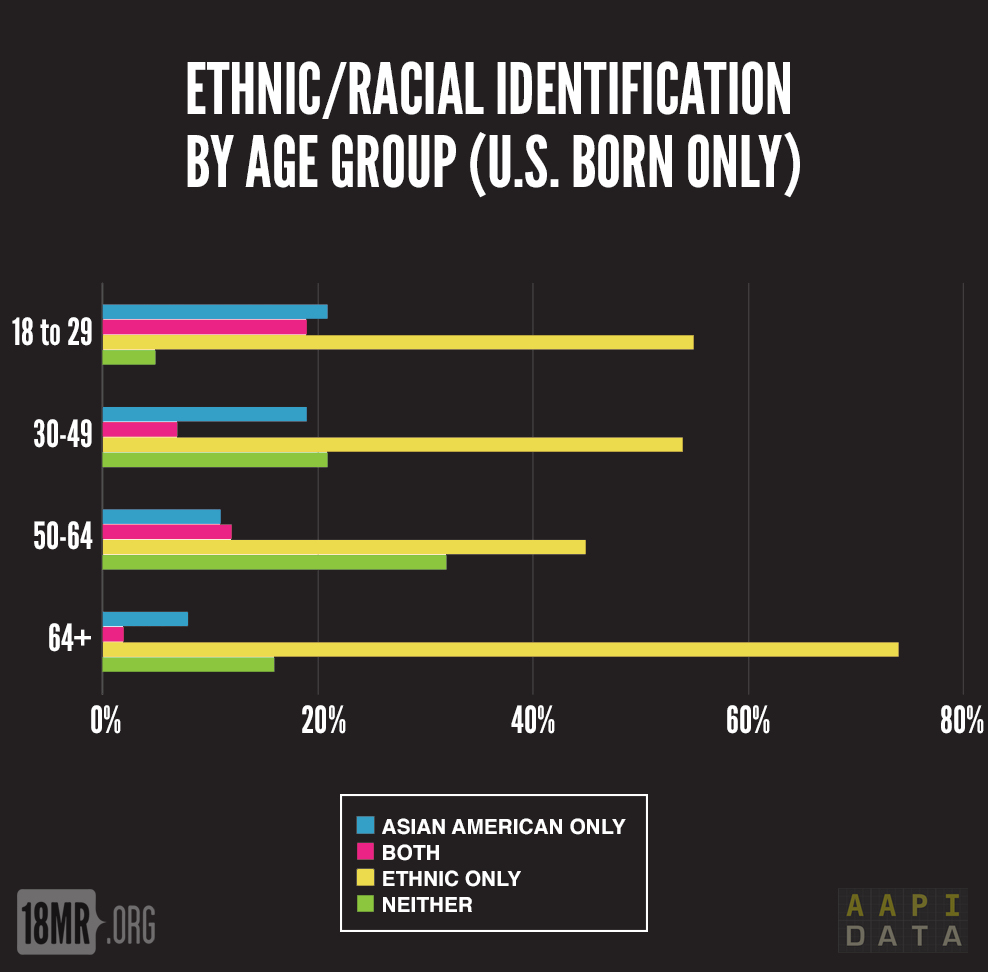

It is not surprising, therefore, that few AAPIs actually identify as such, preferring instead to identify by ethnicity over race. In the inaugural AAPI Voices post for 2014’s Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, Jeff Yang (@originalspin) cites survey data showing that between 50-70% of surveyed Asian Americans reject racial identification with the AAPI community, preferring instead to use ethnic descriptors.

Given these data, we must ask ourselves, has the pan-ethnic AAPI identity outlived its usefulness?

In the late 1960’s, as America underwent a radical change to its perspective on race and racial identity in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement, Asian Americans of various ethnicities (including many who had participated in the Civil Rights Movement) questioned where we stood in America’s racialized landscape: we were neither the intended targets of the racist segregation laws of the Jim Crow South, nor were we perceived to be members of mainstream Whiteness. Grace Lee Boggs, the pioneering civil rights activist who is of Chinese descent, recounts a story of her youth wherein she was riding a segregated train in the South during the 1930’s. A conductor stopped by her seat to inform her she would have to move to the “colored” car; he returned moments later to tell her that he had been mistaken (she refused to move). This story — common for many Asian Americans who lived through Jim Crow segregation– illustrates the uncertain place Asian Americans held vis-a-vis race in America: as Asians, we are viewed as neither Black nor White but instead inhabiting some ill-defined third racial axis that challenges the very notion of race as a binary spectrum.

Through most of its history, individual Asian ethnic groups have numbered in the mere thousands. While some of the larger Asian ethnic groups — for example, Chinese, Japanese, Filipino — were able to achieve some political victories prior to the 1960’s, many of these gains were won in regions where each group lived in high density — in places like California and Hawaii — where our political voices could be amplified over a short distance. For the most part, however, we seemed fated to political obscurity: minority groups individually so small that our interests could be readily dismissed.

Yet, our interests also demanded political attention. Asians of virtually all ethnicities were barred from entry to the United States for nearly 80 years under racist exclusionary laws limiting immigration; those that remained in the country faced daily harassment, discrimination and even outright lynching. Asian Americans like many people of colour were prohibited from testifying in court, naturalizing as citizens, or engaging in interracial marriage. In the 1940’s, the federal government had forcibly imprisoned Japanese Americans en masse. Despite the small size of our community, it was clear that Asian Americans needed a political voice; a hunger that only grew with passage of the 1965 Immigration Act that finally opened a pathway for growth in our population.

In the post-Civil Rights era of the early 1970’s, who would advocate for Asians?

In America, civil rights are defended and opportunities won through collective advocacy: our representative democracy favours large constituency groups who are through organized action able to force an ear for their voices. In this country, you need wealth to be heard; absent that, you’d better have numbers.

Thus, the formation of a pan-ethnic Asian American racial identity was the obvious solution: the coming together of individually distinct voices, artificially united for the purpose of mutual political advocacy. Unique among racial groups in this country, our community was forged not out of commonality, but out of difference, to work together towards a common goal: political empowerment for all.

Divided, we wielded imited political power. But with hands joined, Asians would find the capacity to advocate for ourselves.

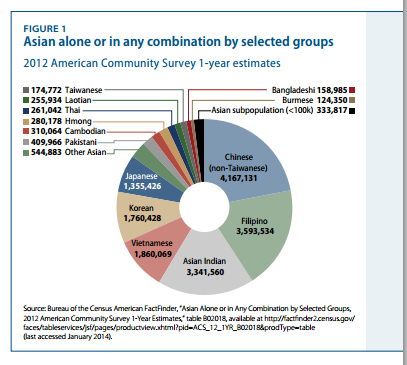

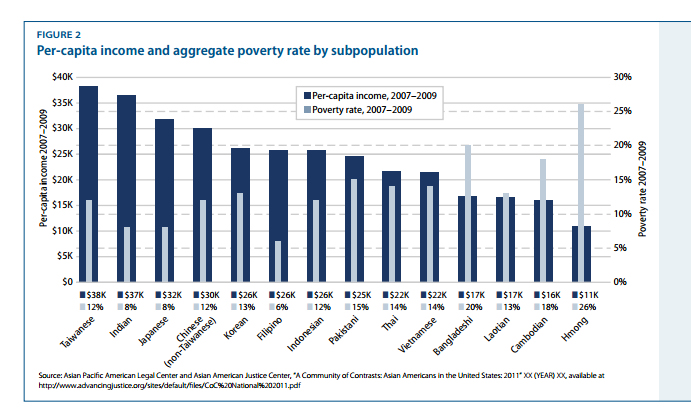

Today, as a combined group, AAPIs represent 19 million Americans, or approximately 5% of the population. Yet, as it always has, our ethnic differences still threaten to fracture the AAPI racial identity. And, for the most part, the dissent is justified. A pan-ethnic racial identity runs the danger of erasing the distinctiveness of individual member ethnicities by applying the economic, linguistic, and cultural characteristics of some ethnicities to all: how many have used the terms “Asian” and “East Asian” synonymously, forgetting the many South and Southeast Asian Americans who also identify as Asian or Asian American?

Southeast Asian and Pacific Islander ethnic identities — minority groups within our minority group — clamour to be heard within the larger cacophony of the AAPI racial identity, and yet are still too often browbeaten into silence. To combat this, Pacific Islanders have successfully advocated the US Census to make this identity a separate racial classification, a necessary step for the disaggregation of federal demographic data to identify PI-specific disparities that will permit federal and state-wide intervention.

In addition, many Asian ethnic groups still bear the scars of political conflicts in Asia and Hawaii, and these inter-ethnic tensions can (rightfully) jeopardize efforts to find common ground in today’s America. As just one example: can solidarity be found when we fail to address the lasting impact of historic and current atrocities committed by Chinese or Japanese governments against South, Southeast Asian, or Pacific Islander peoples, and even between these two governments?

Yet, together, AAPIs can be politically powerful. In 1982, the murder of Vincent Chin reminded us that anti-Asian racism knows no ethnic distinction; in reaction, Asian Americans of all ethnicities joined forces to advocate for justice against Chin’s killers. With our efforts combined, we have advocated for Asian American Studies in colleges and universities across the country, and are enjoying mainstream recognition for our ability to swing national elections. More recently, Asian Americans of multiple ethnicities adopted the cause of 40 Punjabi asylum seekers imprisoned in El Paso for over a year and have been one at a time helping to win their freedom; despite impacting a specific group of South Asian American men, this issue gained momentum in part through the efforts of Asian Americans working towards common cause across ethnic divides. In short, the AAPI pan-ethnic identity continues to produce vast political benefits.

The AAPI pan-ethnic identity is not a panacea, and should not be treated as such. As we continue to debate the benefits and trade-offs of a pan-ethnic AAPI racial identity, I think we must shift our thinking away from AAPI as a singular and monolithic race, and embrace instead the model of AAPI as a racial coalition: one that we acknowledge is an artificial construct, and one that we have the power to shape to emphasize rather than erase our ethnic differences. Too often, we assume that to maintain the AAPI racial identity requires that we speak together in one single “Asian American” voice; yet, this reflects neither the circumstances of our community’s creation nor today’s diversity of the AAPI diaspora. We are not the same; we should not present ourselves as such.

If we are to continue to maintain the AAPI racial coalition, however, we must also commit to doing better. We must make it a priority to reinforce in the mainstream mindset that the AAPI identity is a coalition built of difference. To that end, we should redouble efforts to collect and present disaggregated AAPI data that reveal disparities specific to certain AAPI ethnicities. Armed with that information, we must do better to raise to the forefront the plight of AAPIs whose voices have thus far been silenced: that of Southeast Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, whose communities suffer unique and largely ignored economic and educational disparities that the larger AAPI community rarely addresses.

We cannot continue to allow the narratives of East Asians (and to a far lesser degree, South Asians) to dominate our discourse; instead, we must work harder to adopt the issues of all AAPIs.

Historically, we joined forces in acknowledgement that we are not the same, and we have found over the decades an amazing strength in working together. Today, to identify as AAPI is not to say we are all the same, but to say we are similarly committed to helping one another to achieve racial parity.

In so doing, we must do better to give voice to the rich and incredible diversity of our community even while we unite around common cause. Our ethnic differences will always threaten to fracture the AAPI coalition, but I believe there is greater strength to be found when we are able to work together and help one another in the face of our differences, not despite them.

To read more on this topic: Are We One, or Many? by Jeff Yang | AAPI Voices