Regular readers of the blog will remember my occasional stories of my desperately Americanized childhood: those brief years when my parents would identify some quintessentially “Western” cultural practice, and try to synthesize it for me and my sister — often without ever quite understanding why White people even liked the thing in the first place — in futile, and ultimately comical, attempts by two culturally displaced Taiwanese parents to ensure the proper North American upbringing for their daughters. This is how I saw my first baseball game at Skydome, how my father burnt my first Thanksgiving turkey, and how I choked down my first bowl of oatmeal with the consistency of concrete.

And this is also how enduring the Academy Awards became an annual tradition in my house.

For years, my mother, my sister and I would gather around the television one Sunday evening and “ooh and ahh” over the fabulously-coifed White ladies and gentlemen as they floated down a red carpet a thousand miles away. Later, we would watch the entire Academy Awards from start-to-finish, rarely commenting (my mother would wander off, during the middle parts of the ceremony when the more technical awards were announced). Even after I moved away, the Academy Awards was my Superbowl, and I would relish the night of opulence-by-proxy, printing out nomination cards to keep track of the winners against my own predictions.

But, as the years passed, my interest in the Oscars waned. And now, as I sat mere hours away from the start of 86th Academy Awards ceremony, and I realized that I wouldn’t be tuning in. I realized that I haven’t watched the ceremony in years. I realized that some time in the last decade, the Oscars stopped being relevant to me.

And then, I realized: maybe the Academy Awards were never relevant.

Ostensibly, the Academy Awards are a night to recognize Hollywood’s best: best actors, best directors, best screenwriters, best pictures. It’s a night when we get a voyeuristic pass to watch Hollywood’s 1% crown their own 0.01%.

But we are kidding ourselves if we imagine that the crown means a damn.

The Oscars are determined by the cumulative votes of over 6000 members of the Academy, each casting votes within their own craft. So, directors vote for the best director, actors for the best actor, and so on and so forth. Theoretically, this would allow experts in each field to recognize the most skilled among their own ranks. But, in practice, the Academy Awards resembles nothing more than a middle-school election for class president, motivated less by outstanding merit and more by base popularity.

The politics of the Academy Awards is a long-standing and poorly-kept secret. Hollywood studios spend millions of dollars lobbying for Oscar nominations and votes. From expensive ad buys targeting Academy voters, to extravagant swag bags that reek of unabashed bribery, to the likelihood of backroom deals and more, the race for Oscar votes mirror the kind of political campaigning seen every four years in the race for the White House; differing only in the fact that all of this lobbying occurs behind closed doors and to an exclusive constituency of mere thousands. Yet, just like with presidential campaigns, it’s not usually the most deserving candidate who gets sent to D.C.; it’s the candidate with the most political savvy and the most money. Similarly, those who end the night holding the gold-plated Oscar statue is occasionally, but not typically, the artist who exhibited the most talent or skill in the previous year; he or she is the benefactor of the best behind-the-scenes Oscar campaign.

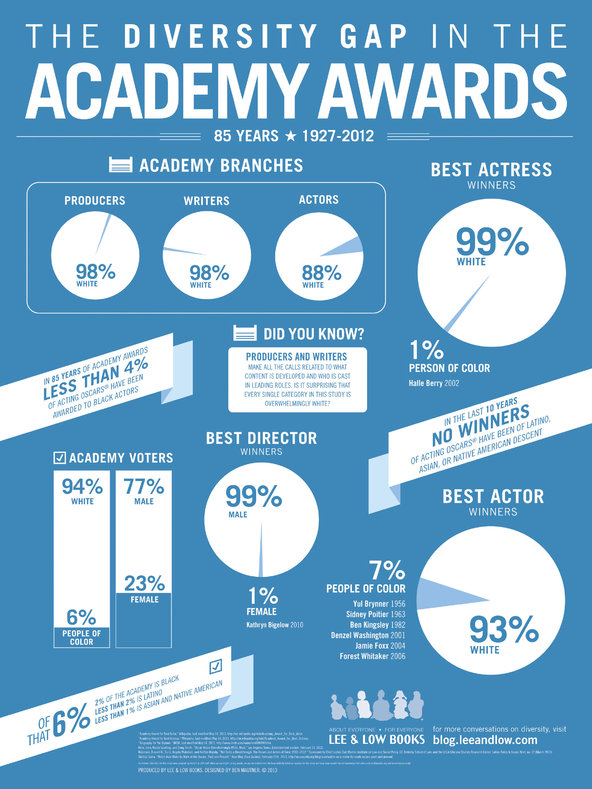

In addition, the Academy is one of the nation’s few remaining institutions that seems to still hang an invisible “White Men Only” sign on its proverbial front door. The New York Times recently published an infographic, revealing the distressing lack of diversity among Academy voters.

Consequently, the Academy Awards rarely, if ever, truly reflect the year’s best movies and actors; from the nomination to the voting process, the system is weighed down by a combination of implicitly exclusionary tradition, politics, and rigid racial homogeneity. Only a certain genre of film — historical epics or dramas — are even seen as “Oscar-bait”; action films, for example, almost never get nominated, and an animated film will not win a Best Picture Oscar within our life-time. Furthermore, the Academy’s demographics result in nominations that exclude well-deserving films featuring talented actors of colour. Instead, year-after-year, the Academy Awards is a parade of Hollywood’s typical elite: the Meryl Streeps and Tom Hanks of the movie world.

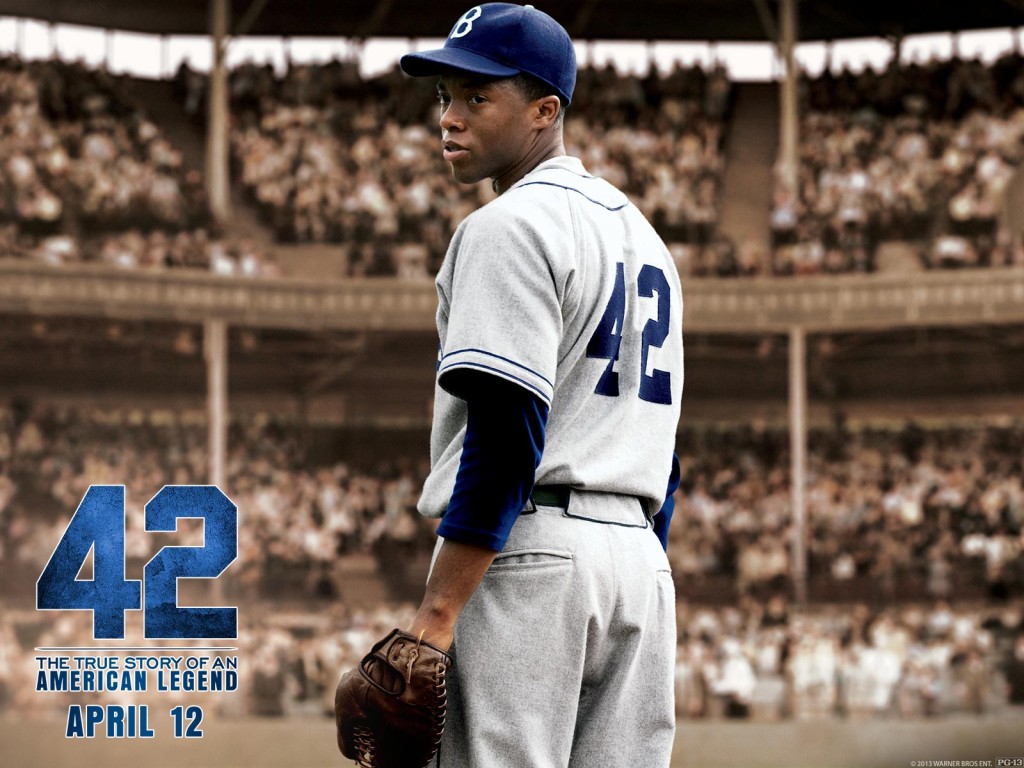

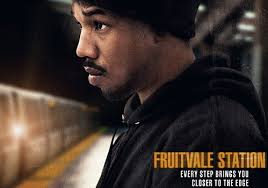

Last year, for example, was by all accounts a watershed year for Black cinema, producing a broad array of great films that explore the Black and Black American experience and featuring predominantly Black actors. 42, Lee Daniels’ The Butler, 12 Years a Slave, Mandela: Long Walk to Freedom, Best Man Holiday, and above all, the incredible and compelling Fruitvale Station starring Michael B. Jordan in a breakout performance.

Yet, the Academy Awards snubbed virtually all of these films, nominating only 12 Years a Slave for an Oscar in a few categories. While this film won Best Director and Best Picture last night, as well as earning Lupita Nyong’o a well-deserved Supporting Actress award, one wonders why this — an American slave epic that culminates in salvataion at the hands of a White saviour — was nominated in the first place. Where was Fruitvale Station, a heart-wrenching tale of the tragic consequences of contemporary American racism that earned resounding critical and box office acclaim?

In fact, in a historic year of Black cinema, only two of nine films nominated for Best Picture — 12 Years a Slave and Captain Phillips — features a multi-racial cast. The remaining seven films features a cast that is predominantly, if not exclusively, White. The same is true for virtually all the films in which a Best Actor or Best Actress is nominated; Chiwetel Ejiofor’s turn in 12 Years a Slave being the lone exception. Adding insult to injury, Meryl Streep is nominated for her role in August: Osage County, a film which featured her character spouting a completely random series of racist jokes in the trailer. Thus, what are we really saying? To validate the Academy Awards is to validate the message that that those whom we consider the best of the best are overwhelmingly White.

The Oscars have been likened to Hollywood’s Superbowl. But, the Superbowl is still ostensibly an objective contest where two elite sports teams have equal chances to win an award. The Oscars are instead more like Hollywood’s WWE: an ostentatious and tacky cry for attention centered around a contest that is clearly rigged.

And, like the WWE, the relevance of the Oscars is waning. Reports show that being nominated for an Oscar alone can account for an extra $35 million in box office revenue for a film. However, reports also show that the worth of an Oscar to film earnings has reduced over the years. And although Oscar viewership went up 19% with Seth MacFarlane as host last year, overall Oscar viewership has gone down by roughly 10% since the mid-90’s.

So, while diversity advocates have repeatedly demanded greater inclusion for people of colour among the ranks of Oscar nominees and winners, I’ve started wondering if this is even a worthwhile project. And, while I congratulate the team behind 12 Years a Slave for their Oscar wins last night, I can’t help but wonder if these are largely empty victories. If the Oscars aren’t really about choosing the best of Hollywood; if they don’t really even translate to major box office earnings anymore; if the Academy is, by its very structure, racially homogeneous and incapable of objectivity; if Oscar night is nothing more than encouraging the 99% to revel in the lives of the 1%; if the awards could be reasonably described as rich and famous White people picking their most favourit-est White person of all the White people; if Ellen can make a joke in her opening monologue that either 12 Years a Slave wins or everyone in the Academy is racist (a clear indication of why that film was being considered this year); then, one must ask: what does winning an Oscar really even mean?

If Fruitvale Station, a low-budget independent film that should be mandatory viewing for all Americans not only for its topic but for the quality of its film-making can’t even get nominated because it doesn’t have sufficient backing to make it through the political campaign process to be nominated, than what is the point of the Oscars? The red carpet interviews? The selfies? The pizza?

Thanks, but no thanks.

I used to love the Oscars, but that was back at a time when I still believed they were a relevant metric of movie-making quality. That was back when I still felt a thrill at seeing a glitz and glam I would never be a part of. That was back when I was still a kid, and thought that seeing someone — even someone who looked like me — win an Oscar meant something.

But I’m grown up now. I don’t need the pretentious fantasy of the Oscars to escape the drudgery of my life any more, and I’m apparently more capable than the Academy of judging great movie fare. And I really don’t need to support an institution that still counts people of colour and women as less than a quarter of its membership, and which is in 2014 still marking racial firsts; and in the case of last night, marking a racial first while explicitly touting how progressive the Academy is for throwing people of colour that bone in the first place.

So yeah, last night, I didn’t watch the Oscars. I was busy live-tweeting the The Walking Dead, instead.