By Guest Contributor: Michelle Lyu

The article was originally published on the Organization for Positive Peace blog.

History is changing and the minds of Asians are bending as they search for a world beyond whiteness. The crises of 2020 exposed America’s moral failure to regard its own people as human. Meanwhile, despite tremendous Western propaganda, China has not perpetrated the kind of imperialistic wars which have marked centuries of rule by the West and is instead seeking to govern on the civilizational value of peace. As America slips from dominance as the world’s predominant military, economic and political superpower, China is poised to take its place as the new global power with a new leadership, guided by moral principles rather than sheer might.

Within America, Asians are on average the most successfully integrated immigrant group into the dream of white elite life. Young, educated Asians are placed at the helm of productivity and expertise within prestigious American universities and corporate business. Liberal media and institutions celebrate the inclusion and visibility of western-thinking Asians in the name of diversity. Many young Asian Americans achieve ultimate material success early in their careers as academics and professionals yet they live in spiritual crisis, unable to reconcile their place, purpose and identity as people who have subsumed the damaging ideals of the west. In reality, an Asian who has ‘made it’ is strategically positioned by the American ruling class to serve as a bulwark of American empire by defending and propagating western ideology, which assumes dominance and exploitation of the darker nations of the world.

History is changing and the minds of Asians are bending as they search for a world beyond whiteness.

On the cusp of integration in 1960, Black people faced a turning point in their relationship to white supremacy. At this time, revolutionary scholar W.E.B. Du Bois wrote about the different paths possible for the African American people. In ‘Whither Now and Why’ Du Bois insisted the Black community would have to struggle to maintain a sense of values and identity wholly separate from those of the dominant white America. “Are we to assume that we will simply adopt the ideals of Americans and become what they are or want to be; and that we will have in this process no ideals of our own? That would mean that we would cease to be Negroes as such and become white in action if not completely in color.” He identified the critical need for the Black community to merge the struggle for civil equality with the preservation of moral principles and non-white culture instead of adopting the decadence, selfishness and inhumanity which define whiteness.

Over half a century later, the Asian’s achievement of equality within a western superpower past its peak of world dominance — a cracked empire crumbling, sets the stage for a new reckoning with their lives and a new hope for the collective trajectory of the Asian American. In the coming years the Asian American will be pushed to reassess their role in the American and world racial system. They will face the choice between defining their lives by the culture of empire or by the principled, moral foundations of the anti-colonial struggles of Asia and in the Black Radical Tradition, that hold the seed of a new world for humanity set to blossom.

Adopting Revolutionary Ideals

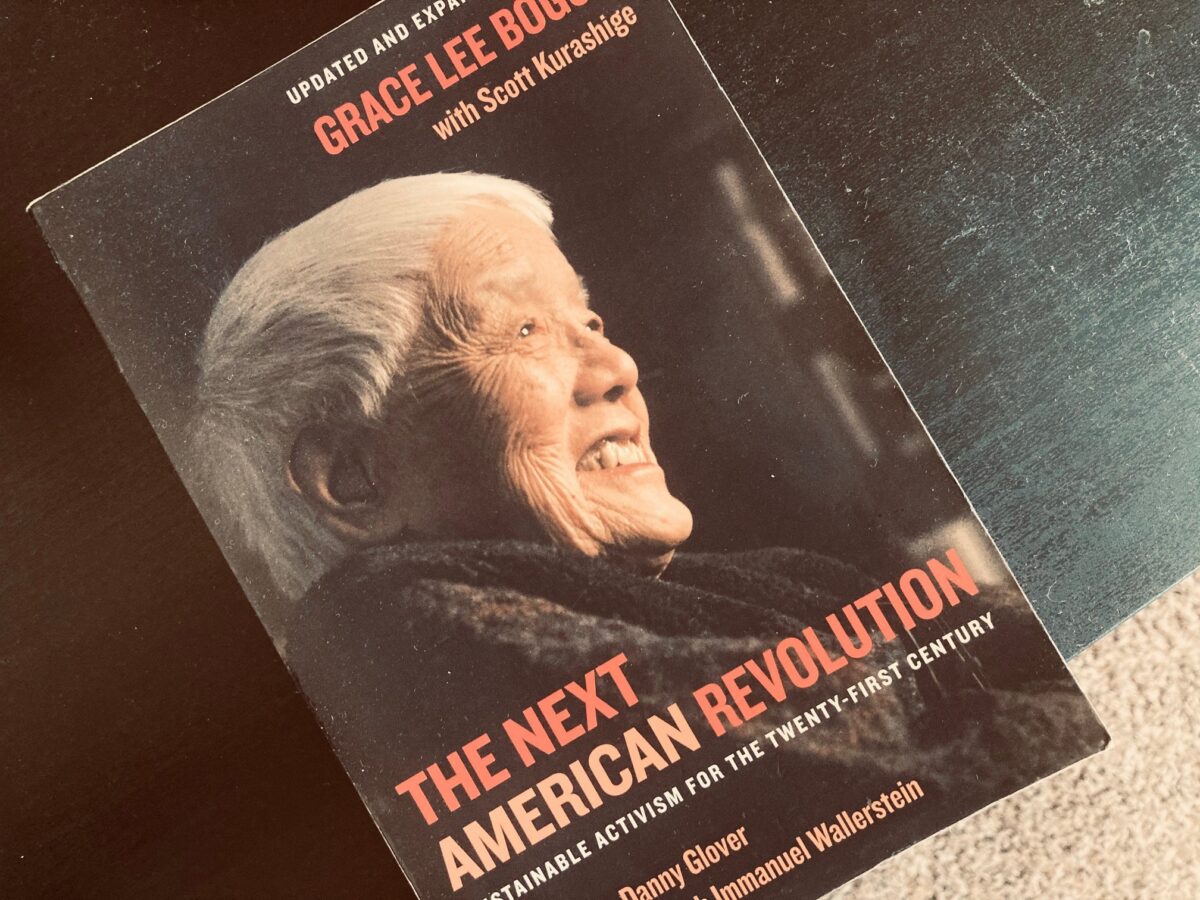

What is the potential of the Asian American today? The crucial responsibility and potential of the 21st century Asian American can be understood through the example of Detroit Black freedom movement activist Grace Lee Boggs, who lived as an observer, participant and transformative force through one hundred years of changing history. During our era of ideologically chaotic and morally irresponsible leadership among Asians in academia and activism today, Grace’s legacy serves as a bedrock of clarity. Although she has been popularized in mainstream Asian American circles, the significance of her life’s history and commitments is usually misunderstood. Her legacy and significance must be understood to be much broader than the narrow image of her as an Asian American activist, and to be larger than the framework of identity politics.

Today, Asian Americans who become socially conscious are often politicized through academia or digital media which often has stagnant and nihilistic dogma. Mainstream activism believes progress either comes from assimilation or rejection: the liberal rises up the ranks of white America, the radical learns to reject their parents and homeland as irreparably backward. They are taught to think and act as victims, guiding their lives and commitments by feelings of rebellion, shame, resentment and guilt. These ideas are premised on the assumption that Asians can define themselves simply through negative reactions to injustice. But what people need is the opportunity to live a life rooted in the positive — with bright hope in their hearts, a steady foundation of moral values and the belief that the world can be remade.

What made Grace distinct from Asian American models of leadership offered to today’s youth was her lifelong commitment to the journey of developing revolutionary ideas rooted in morality, hope and a responsibility to humanity. She regarded her Chinese American identity as having blessed her with the consciousness to conceive herself as an active force for change in American society. In her autobiography she wrote, “Had I not been born female and Chinese American, I might have ended up teaching philosophy at a university, an observer rather than an active participant in the humanity-stretching movements that have defined the last half of the twentieth century.”

What made Grace distinct from Asian American models of leadership offered to today’s youth was her lifelong commitment to the journey of developing revolutionary ideas rooted in morality, hope and a responsibility to humanity.

Grace’s philosophies developed in a unique historical moment — the 1930s, defined by the Great Depression, New Deal and rising labor movement. As the United States prepared for World War II, she became involved in anti-war activities with a sense of responsibility. Having just finished school, she relocated to Chicago in her 30’s, where she organized with the Black community and joined the Trotskyist Workers Party. At the end of World War II, she observed the waning energy and the disconnect to reality in the American white left and broke from the Trotskyist movement in order to work among social forces who she believed could provide the revolutionary leadership needed to transform society.

Her move to Detroit in 1953 marked a radically new chapter of her life, where she joined the Black community’s struggle for self-determination and married Jimmy Boggs, an auto worker from the South who became her lifelong political partner. In the following decades, she became a leading figure of Detroit’s Black Power movement. Recognizing the central role of education in arming people with the ability to imagine freedom in a changed society, she worked tirelessly to develop a revolutionary consciousness among the community through political pamphlets, journals, meetings and organizations.

Grace understood ideas were foundational to fundamentally transforming society and rooted her identity in her capacity to live a life of moral courage and revolutionary ideals. In the early 1970s Grace wrote, “Revolutionary thinking begins with a series of illuminations. It is not just plodding along according to a list of axioms. Nor is it leaping from peak to peak. Revolutionary thinking has as its purpose to discover where man/woman should be tomorrow so that we can struggle systematically and programmatically to arouse the great masses of people to want to go there.”

Uniting Afro-America and Asia

As Grace did for her time, young Asians today must develop a revolutionary paradigm for change that unites the external with internal struggle and that pursues the truths of reality in order to create a new society. As 2021 dawns, the Asian American’s task is to forge a new identity defined by unwavering commitment to peace and justice. How can this be brought about?

We must address who the Asian American is. Facing class, race and ideological differences, the Asian American identity cannot be coherently consolidated by demographic labels. There are well-educated darlings of the elite, poor workers, urban and suburbanites, adoptees, multi-racial Asians and recent immigrants who frequently maintain conflicting interests.

Rather, the genuine basis for unity among all Asians is found in historic principles of peace — thousands of years of Asian civilizations thriving with art, beauty, intelligence, human uplift and peaceful co-existence, continuously evolving toward new ideals of a complete society. For hundreds of years the countries of our forebears have shared historic struggles against colonialism — from China and Korea, to Vietnam and Cambodia, to India and Pakistan. The movements of these masses of people who readily sacrificed in defense of the freedom for a world based on the uplift of mankind, against domination through war, profit and human exploitation, forged a distinct moral tradition rooted in courage, love and a peaceful vision of humanity.

Being Asian in America also means that we must understand ourselves in relationship to the Black struggle, which has been central to shaping the economic and social development of American society. Current left politics and academia encourage Asians to relate to the black struggle by false equivalency, in which anti-Asian racism is severed from its roots in anti-Black racism, or by guilt, in which Asians believe they have nothing to contribute to the Black struggle beyond charity or distanced sloganeering.

Being Asian in America also means that we must understand ourselves in relationship to the Black struggle, which has been central to shaping the economic and social development of American society.

Both of these extremes neglect the reality that the Black American struggle, like the historic ant-imperial struggles of Pan-Asia, was striving for genuine democracy and the freedom of all humanity. here is already a genuine foundation for unity between Asian and Afro America: a commitment to peace for humanity, which means an end to war, poverty and degradation of the world’s masses.

W.E.B. Du Bois writes, “That dark and vast sea of human labor in China and India, the South Seas and all Africa; in the West Indies and Central America and in the United States–that great majority of mankind, on whose bent and broken backs rest today the founding stones of modern industry–shares a common destiny.”

Past revolutionary movements like the Indian Independence Movement under the leadership of Gandhi, Vietnamese anti-colonial movement under Ho Chi Minh and the Civil Rights Movement under Martin Luther King Jr. understood the interlocking nature of racism and imperialism.This connection was made when these leaders recognized that a battle against race and a battle against empire were inextricable, and that national movements needed to be brought to an international scale, in which there was a globally united opposition to the dominant Western forces of violence, war and empire.

During the Vietnam War, much of the Black community adopted the battle of the Vietnamese as their own battle for justice under the model of leaders like Muhammad Ali and King. In his groundbreaking 1967 speech ‘Why I Oppose the War in Vietnam’ King said, “I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today, my own government.” This kernel of truth, that genuine anti-racism is also a fight against war and poverty, holds great implications for what revolutionary change in our times could be. If all the people who claimed “Black Lives Matter” were prepared to condemn the Democratic party’s perpetration of endless wars, we would be envisioning a very different world.

The possibility of peace is starkly absent from the consciousness of the younger generation who never had the opportunity to see and learn from the unfolding of the twentieth century’s genuine revolutionary movements. Removing America’s racism from the context of a global struggle against war and poverty has led to staggering co-optation of people’s sincere efforts to do what is right, resulting in the uncertainty and confusion which underlies contemporary protest and activism. If finance, tech and retail giants which flourish at the expense of the Black working class have the authority to proclaim that they, too, believe “Black Lives Matter,” then what are we really marching for?

‘Anti-racism’ has become a popular signifier of commitment to ending racism, but it is often only rhetoric which asks no moral courage nor sacrifice from the people who claim the term. The real substance of anti-racism must be the desire for the world’s people to become free. If this is our genuine commitment, then we must take a stand against America as the global purveyor of war. This is especially important as Asian Americans, who are typically taught to reject Asia as backward and culturally oppressed while ignorant of the crimes of the West.

The real substance of anti-racism must be the desire for the world’s people to become free.

Because war, race and poverty are inextricably linked, establishing race in the context of empire and poverty is necessary to the struggle of genuine equality which the Civil Rights movement strove for. In order to achieve this, we must root ourselves in the Black freedom struggle, the singular movement in American history to have fought for the democracy of all humanity. We must engage in a genuine study of foundational thinkers such as W.E.B. Du Bois, James Baldwin and Martin Luther King Jr., and seek unity with the most progressive forces amongst Black people.

The Struggle for Humanity’s Freedom As Our Inheritance

A synthesis of the struggle for Black freedom and world anti-colonial struggles will guide the forward-thinking Asian American today. These blueprints of struggle provide a paradigm for revolutionary change which make sense of a world changing in motion, unites external with internal struggle and develops the truths which can make a new world possible. By understanding the contradictions of an imperial society built on the degradation of race and labor, Asians within America are capable of uniting the internal struggles of American society to the struggle for world peace and unity. It is this Asian American, clear and conscious, seeing beyond the fetish of western propaganda who can help furnish the ideas needed to produce a future which stands not on war and decadence, but on peace and the flourishing of world humanity.

In the status quo, stagnancy, depression and spiritual emptiness frequently afflict Asian Americans because they adopt a white identity by default: measuring themselves by white standards, thinking as white people do and making choices by white principles. Despite economic and professional riches, they do not feel free because adopting white values degrades one’s sense of humanity.

In discovering what it means to become Asian American, the complete answer will unite the anti-colonial principles of the East with the distinct responsibility of being in America. Therefore, in practice and thought we must continue the recent history of the Black freedom struggle, the only political tradition produced by America which has sought to elevate the development of humanity as a whole, while also basing ourselves in the principles of Asia’s anti-colonial struggles which draw on thousands of years of history. These great moral legacies are the natural inheritance of all people who yearn for a new future, and in continuing to discover how they can guide our times, we reach the possibility of linking our personal struggle for purpose and identity to the universal struggle for freedom.

Michelle Lyu is a 23-year old Chinese American originally from the San Gabriel Valley, a densely Asian-populated region of California. Michelle has lived in Philadelphia for the past five years and is a member of The Saturday Free School for Philosophy and Black Liberation based in North Philadelphia at the historic Church of the Advocate. Michelle’s political work is focused on the building of principled unity between the Asian and Black community.

Learn more about Reappropriate’s guest writing program and submit your work here.