Three years ago, Ellen Pao — former junior partner of Silicon Valley venture capital group Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers — filed a lawsuit against her former employers, citing a pattern of bias against female employees; yesterday, lawyers in her suit against Kleiner completed their closing statements with a plea for greater efforts to address gender equality in the tech industry. Pao’s suit alleges that Pao was harassed, and eventually fired, from Kleiner for challenging a culture of sexual harassment within her former company.

Throughout the Pao trial, Pao has courageously endured the usual victim-blaming, character assassination and mudslinging used to dismiss, invalidate, and insubstantiate the experiences of women. She has been tone policed. She has been slut-shamed. She has been labelled a gold digger. She has been accused of being untalented, amateurish, and unprofessional. The message Kleiner’s lawyers are trying to communicate is clear: Ellen Pao is lone voice trying to capitalize off an imagined gender problem in Silicon Valley.

The problem for Silicon Valley is that Ellen Pao is not alone.

Last week, Taiwanese American Chia “Chloe” Hong filed a civil suit against Facebook for gender discrimination. Days later, software engineer Tina Huang filed a civil suit against Twitter, also alleging gender discrimination in the company’s failure to promote women to management positions.

It should escape no one’s notice that all three of these high-profile gender bias lawsuits have been filed by Asian American women.

Geek Bro Culture

The tech industry’s “gender problem” has been a topic of conversation for several years, and is representative of the larger “Geek Bro Culture” phenomenon within such traditionally nerdy spaces like comic books, video games and — yes — the tech industry. As with comic books and video games, the growing visibility of women in communities stereotypically male-dominated has prompted broad, and inflammatory, gendered backlash: within the video game industry, for example, feminist programmers and culture critics face a daily barrage of sexual harassment and death threats. Among comic book fans, feminists are disparagingly labelled as bullies in the midst of fielding death threats of their own for questioning the medium’s reinforcement of sexism and rape culture.

Arthur Chu (@arthur_affect) — who has developed a strong portfolio of feminist writing as it intersects with geek culture — suggests that within geek culture, nerdy men who simultaneously reap the benefits of male privilege while disadvantaged by a culture of misogylinity are left with a deep-seated entitlement complex over women. In these insulated spaces, “Geek Bro Culture” recreates a gendered hierarchy where male nerds can achieve the “alpha male” status denied to them by mainstream’s toxic masculinity. Rather than to challenge the logic of misogylinity, “Geek Bro Culture” recreates its male privilege with none of the troubling aspects of conventional masculinity that would disadvantage male programmers (anti-intellectualism, for example); thus, these becomes spaces not only hostile to women, but spaces dependent upon its hostility to women.

It would be naive to suggest that within these spaces — as within the larger mainstream –race is not a factor in manifestations of sexism.

“Misogynasian”

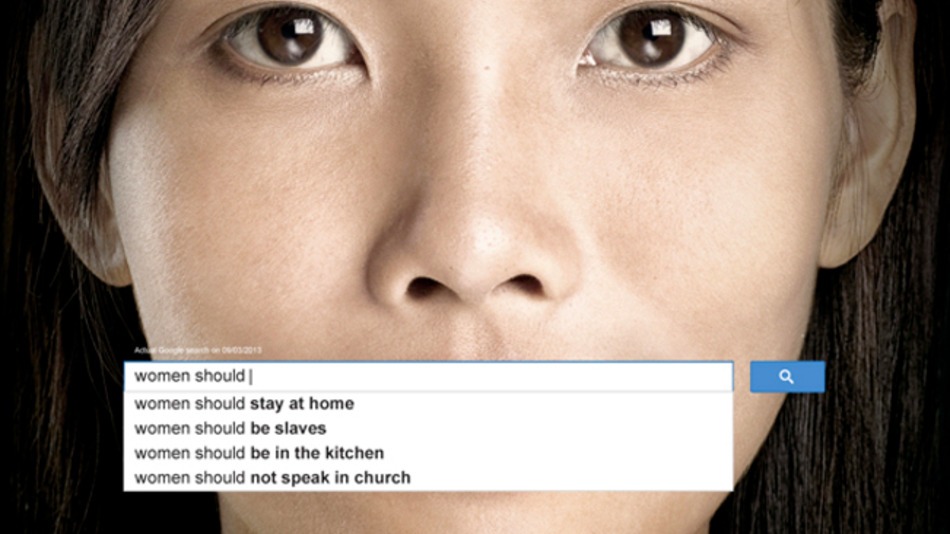

Traditionally, we have applied a “one size fits all” approach to our understanding of misogyny, yet increasingly we have come to recognize how race intersects with and nuances manifestations of sexism and misogyny. For Asian American women, too, misogyny takes on a distinct flavour.

A recent report on the gender bias faced by women of colour in STEM reveal the distinct stereotypes that form the foundation of gender discrimination in the workplace, and how intersections of race matter therein. Consistent with society’s larger treatment of Asian American women, Asian American women in STEM are stereotypically relegated to the role of the submissive, the demure, and the unassuming. Frequently, we are positioned as the “wedge female” — more feminine, well-mannered, and eager-to-please than our non-Asian female counterparts. We are expected to model “acceptably feminine behaviour” for the “uppity” and aggressive non-Asian woman. We, as Asian American women, are stereotyped as knowing our place.

Asian American women describe how this insisted femininity frequently causes Asian American women to be over-looked and disrespected in the workplace. Like many Asian American women, Tina Huang says she was passed over for promotion at Twitter despite her demonstrated talent. Like many Asian American women, Chia Hong describes how male colleagues at Facebook belittled her for not being a stay-at-home mom while demanding she play the gendered role of den mother for the office. Like many Asian American women, Ellen Pao describes how she was expected to be sexually available for her male colleagues, and faced frequent unwanted sexual advances while working at Kleiner.

Thus, in STEM, as in the wider world, “misogynasian” persists as a method to reinforce Occidental and male control, thereby prohibiting the Asian American woman from ever being seen as an intellectual peer. Misogynasian has quantifiable consequences: in STEM, Asian American women face institutional barriers by virtue of both race and gender — a “bamboo glass ceiling” — that delay upward mobility and cause large numbers of Asian American women to exit the workforce. Those that remain endure one of the largest pay gaps of any women of colour: Asian American women are paid a mere 79 cents to the dollar paid to an Asian American man.

Those Asian American women who speak out against this racialized and gendered mistreatment face heightened backlash precisely because “leaning in” directly contradicts the logic of misogynasian. 61.4% of Asian American women in STEM (a larger proportion than any other women of colour) report that they have been unfairly disciplined or mistreated for refusing to perform as meek, subservient and hyper-feminine.

The stereotype of Asians as passive plays a role. A geophysicist noted the expectation “that Asians are supposed to be very passive. And when you add women to that, they really don’t expect Asian women to stand up for themselves, or they expect the dragon lady, the extreme opposite. You can’t just be a normal person. There’s no expectation for you to be normal.” An Asian in viral immunology agreed, saying that, as an Asian, she was seen as someone who “should be like feminine, yeah. Shouldn’t be aggressive.”

Misogynasian asserts that Asian American women exist to reinforce White male superiority; it is a tool to reinforce both White and male privilege. Those of us who refute misogynasian’s claims by asserting our own individuality and agency as Asian American women are therefore punished, oftentimes more harshly, for daring to defy this racial and gendered logic.

A note on the word “misogynasian”: first of all, yes, I’m aware that I just made another word up; it’s okay, people do it all the time. Second, my intention is not to be appropriative of the “misogynoir” movement, although I acknowledge the possibility that this term could be thus interpreted. For quite some time, this blog has been committed to discussing the unique intersection of racism and sexism as faced by Asian American women; this is a conversation I’ve long felt has been impeded by a lack of language that can describe these concepts with specificity, and I’ve been toying with words to propose for this concept for over a year now. After considering a few other portmanteau words (e.g. “Sexorientalism”, “Misaapigyny”) , I propose that “misogynasian” offers the most easily pronounced word construction with the most obviously discernible definition; by contrast, I feel “misaapigyny” works but is hard to pronounce while “sexorientalism” is confusing. However, the possibility of “misogynasian” being appropriative of “misogynoir” is a real and legitimate issue, and is my major concern with presenting this word. Thus, I invite commentary and criticism on this proposal.

(Update: There has been some confusion as to whether “misogynasian” is intended to refer to the nuanced misogyny experienced by Asian American women, or to some sort of specific brand of misogyny perpetuated by Asian American men. To clarify, “misogynasian” refers only to how anti-Asian stereotypes alter the misogyny faced by Asian American women. As this section discusses with references to my prior writing, there is a clear layering of race and gender in how Asian American women experience sexism in tech and in the larger mainstream, but no language with which to discuss this. This section endeavours to offer a solution to that problem.)

Asian Americans and Male Privilege in Tech

The tech industry is absurdly male-dominated: on average 12% of tech company employees are women. Even some of the country’s top software companies like Google and Facebook — traditionally viewed as progressive — employ more than twice as many men as women.

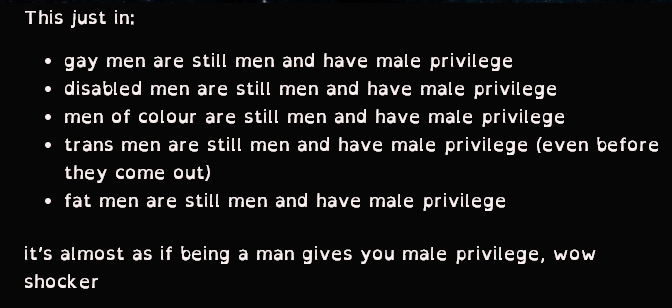

The tech industry is dominated by White programmers, but increasingly by Asian American programmers, too. In 2010, reports showed that for the first time, more than half of the Bay Area’s tech employees were Asian American. Many of the male partners cited by Ellen Pao as contributing to the culture of sexual harassment at Kleiner are Asian American.

Let me be clear: in no way am I saying that the tech industry is sexist because of Asian American men. Orientalism — one of the central influences of misogynasian — dates back to European assertions of its own colonialist and militaristic supremacy over Asia. The tech industry’s “bro culture” also clearly pre-dates the rise of the Asian American male (or female) programmer. In many of tech’s top companies (including Facebook and Twitter), White employees still outnumber Asian American ones. Asian American male programmers obviously do not benefit from misogynasian’s foundational logic of White supremacy; in fact, we embrace the fight to challenge STEM’s persistent “bamboo ceiling” for the advancement and promotion of Asian American male programmers.

However, if Asian American programmers enter tech industry’s White-originated “bro culture” where we can criticize residual White supremacy and anti-Asian stereotypes, but refuse to challenge its inherently sexist parallel logic (including its reinforcement of misogynasian), our community nonetheless remains complicit in the survival of that culture of racial and gender bias. So long as we can witness — and our brothers can even derive the benefits of male privilege from — a culture that harasses women (including Asian American and other women of colour) while shrugging our shoulders and saying, “it’s not my problem”, we are failing Asian American women while undermining our own race advocacy efforts.

For too long, our community has been resistant to talking about gender discrimination, even when it privileges Asian American men and disadvantages Asian American women. Some of us have asserted that feminism is a “women’s issue” that has no place in Asian American race advocacy. Some of us actively discourage the framing of Asian American men as simultaneously disenfranchised by race while privileged by gender. Some of us go so far as to delegitimize the Asian American feminist for her feminism. Instead, some of us seem convinced that a conversation about male privilege will somehow undermine the equally legitimate conversations about anti-Asian American racism against Asian American men (and women). In so doing, we implicitly reinforce the notion that the politic of the Asian American woman should take a backseat to that of Asian American men; that, even within our own Asian American community, Asian American women should play the role of the submissive, subservient and meek; that Asian American women must somehow accomplish the impossible task of divorcing our race politic from our gender politic, as if the two can be distinguished.

The fact of the matter is that — by virtue of our privilege — Asian American programmers are in the room in a way that other programmers of colour are not. By the virtue of their privilege, Asian American male programmers are in the room in a way that Asian American female programmers are not. In the aggregate, Asian Americans wield a numerical majority in Silicon Valley’s culture (even while we are excluded from leadership roles). If we as a community united to take a strong political stand against both racial and gender discrimination in the tech industry — as it disadvantages both the male and female Asian American programmer and any other programmer of colour — we could promote a cultural sea change against tech’s ongoing harassment of minority engineers.

Yes, I believe Asian Americans could help dismantle “Geek Bro Culture” and achieve gender equality in tech: if only we would finally prioritize the misogynasian faced by our Asian American sisters as politically compelling; if only we would finally position feminism alongside our existing efforts to promote racial equality; if only we would finally do the necessary work to identify how male privilege doesn’t benefit White men alone, but can and does cross racial lines; if only we would finally acknowledge that gender equality is not just a women’s issue, but a social justice issue; if only we would finally hold ourselves accountable to challenging all forms of social and political iniquity arising out of the mainstream even as it might privilege us individually and collectively; if only we would finally recognize gender equality as an Asian American issue, too.

Read more: How Asian American women are forgotten in the tech diversity debate (Think Progress)

Update II: With regard to the term “misogynasian”, I want to emphasize that my purpose is to spark conversation about the intersection of race and gender when it comes to the misogyny faced by Asian American women. I am not invested specifically in the term “misogynasian” so much as I am interested in advancing its underlying meaning, and although I think this term is the clearest and most readily understood of possible candidates, I also use the word with hesitation and tension given the currently still completely unaddressed possibility that it overlaps too heavily with “misogynoir” and surrounding Black discourse.

I do not find this criticism trivial, and I am actively soliciting feedback on “misogynasian”. I am embedding this Twitter conversation with reader @sqiouyilu, who raises the same valid concerns over the term, because I think they bring up very important points to consider.