With the explosive popularity of the #NotYourAsianSidekick Twitter hashtag — and associated mainstream media coverage — some are encountering notions of Asian American feminism possibly for the first time. A subset of those question whether or not Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) women experience any form of race- and gender-based discrimination.

This is the first in a series of posts aimed at presenting data on the institutional sexism that affects Asian American women (and by extension other women of colour).

Feminists have long known about the gender income gap, which shows that in aggregate women earn approximately 75 cents to the dollar earned by their male counterparts. One of the more surprising statistics out there, is that when the gender income gap is subsequently stratified by race, the gender income gap is widest within the Asian American community compared to their male counterparts. In fact, Asian women earn 73% the income of Asian men (compared to 81% for income of White women vs White men). While this statistic is tempered by the fact that AAPIs on the whole — i.e. both men and women — are bringing home a much higher median household income than folks of other races, the wide gender pay gap within the Asian American community demonstrates clear evidence of a strong gender-based disparity faced by AAPI women that goes largely unaddressed in our community.

But, some might wonder, what does this number really mean? What are the factors that lead to such a discrepancy in earning between AAPI men and AAPI women?

Asian Americans represent approximately 5% of the total American population, with roughly 60% (and falling) of our community representing foreign-born citizens. Due to the self-selective impact of the immigration process (which disproportionately supports legal entry of wealthier and more highly-skilled immigrants and their families), Asian Americans are marginally over-represented (relative to our overall population size) in higher education. Yet, despite these figures, the gender income gap persists for Asian American women for many reasons.

The Wide Asian American Wealth Gap

Part of the reason is that the Asian American community’s wealth gap is far wider than that of other races: while a subset of Asian Americans are earning higher median incomes than the general population, a larger-than-average subset of Asian Americans are also living below the poverty line and experience significant obstacles towards higher education and income. This produces a greater-than-average chasm between the richest Asian Americans and the poorest Asian Americans than we might see in the population at-large; yet, because of the high visibility of successful Asian Americans, this wealth gap goes largely unnoticed.

It may come as no surprise that among poor Asian Americans, women are over-represented compared to their male counterparts. The Center for American Progress provides a list of facts about Asian American women in poverty compiled from the US Department of Labor and Statistics, that show that in 2011, 12.3% of Asian American women lived in poverty (vs 9% of Asian men), and that the number of Asian American women earning less than minimum wage has doubled in the last five years. So while a large fraction of Asian American women are earning degrees and entering the job market, a large fraction of Asian American women (particularly Southeast Asian women) are also trapped below the poverty line.

Educational Attainment

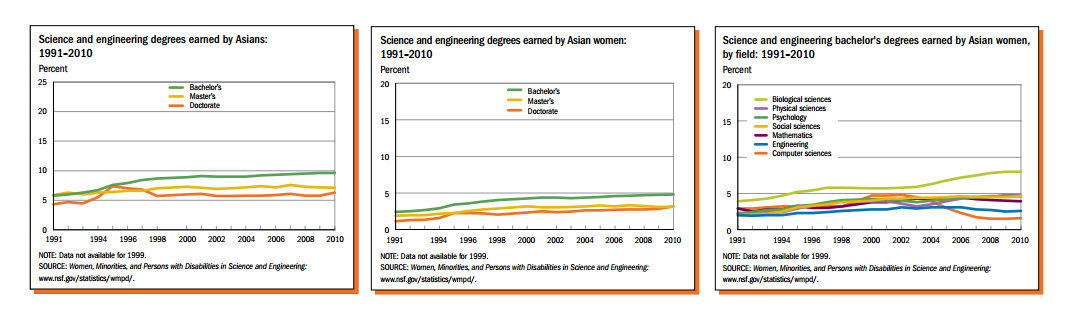

As mentioned above, Asian Americans are somewhat over-represented in higher education. Interestingly, most statistics suggest that Asian American women who have access to higher education are equally as likely as our male counterparts to earn and receive college degrees. Specifically, Asian American women are 54% of the Asian American population, and we are approximately 54% of Asian American bachelor’s, master’s, and post-graduate degree recipients. However, it’s worth noting that this is a novel phenomenon: less than ten years ago, Asian American women (as well as women of other races) were receiving degrees at far smaller rate than their relative population size.

Nonetheless, it’s also clear that while Asian American women obtain schooling at numbers roughly appropriate to our population size, there remains gender-based barriers for Asian American women entering STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics). A STEM-related education confers access to some of the most highly-paid jobs available in the current market: some studies show that a STEM bachelor’s degree can boost median household income by anywhere from $10,000 to $40,000; further, the top 10 highest-paying bachelor’s degree majors are all in STEM fields.

According to the National Science Foundation (NSF) Asian American women, like women of most races, earn less than half the STEM degrees conferred to students of their race, and the growth in attainment of these degrees is slower for Asian American women than for the Asian American community at-large. Within that population, Asian American women are least likely to obtain high-income engineering and computer science degrees.

That being said, one could easily argue that Asian American women are (in general) earning our fair share of advanced degrees in STEM (which is my overall conclusion from the statistics I’ve seen). The obstacles, in my mind, come from difficulties Asian American women face in applying our degrees in the job market.

The STEM Glass Ceiling

I focus here on STEM because 1) the NSF published a nice comprehensive study on this subject which I am drawing heavily from, and 2) I am in the STEM field, so these data hold personal relevance to me. Nonetheless, a similar story is likely to be true for other industries.

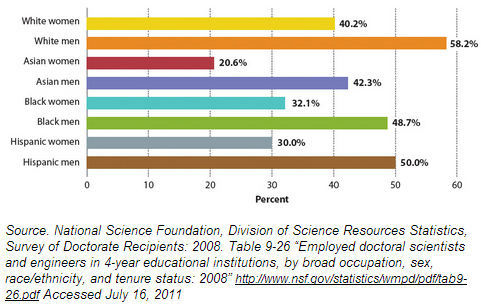

Asian Americans report the highest rate of workplace discrimination of all groups — 30-31% of all AAPI report some form of race-based barrier to advancement (although only 2-3% of complaints filed to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission are from AAPI complainants). Within the STEM field, there exists innate barriers to achievement for Asian American female scientists. Specifically, despite earning roughly the same number of total degrees and STEM degrees as Asian American men, Asian American men outnumber Asian American women by 2 to 1 in the STEM workforce.

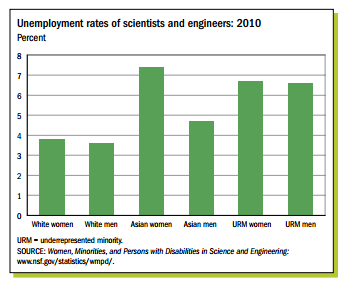

Asian American women report the highest unemployment rate of all men and women in STEM, as well as the second highest rate of working only part-time.

Women of all races, including Asian American women, report unemployment largely because we find the STEM industry to be unforgiving towards women looking to start a family; indeed, the most cited reason for female unemployment in STEM is “family”. This, points to one of the major glass ceiling issues for women in STEM: the desire to start a family is — but should not be — professionally punitive for women, particularly since it is not so for men. Yet, the most competitive time for men and women in STEM coincides with when young scientists are in their thirties and looking to start a family; many female scientists find themselves forced to leave their jobs (often permanently) or to take a long hiatus from their professional careers due to failure of STEM to support the needs of a young parent.

But, the desire to start a family aside, a larger proportion of Asian American women (vs. White women) also report either “laid off” or “no job available” as their primary reason for unemployment, suggesting that in addition to the responsibilities of caring for family, Asian American women are also suffering from greater difficulties establishing themselves in the STEM job market upon graduation.

These obstacles are significant barriers for achievement for Asian American women, resulting in a debilitating “slow-down” in professional advancement. STEM degree-holding women (of all races) are less than 25% of full-time faculty positions at research institutions, compared to men; conversely, this indicates that women are being excluded from STEM’s top jobs.

For additional analysis of how Asian American women are significantly underrepresented in managerial positions throughout the STEM industry, please see this article.

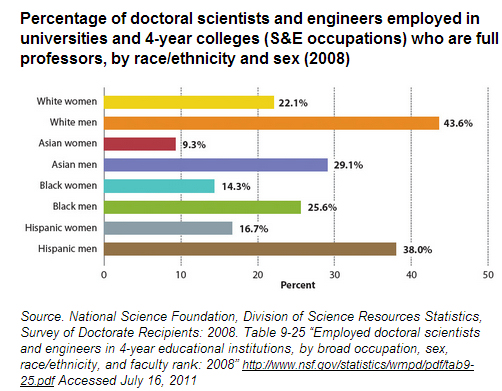

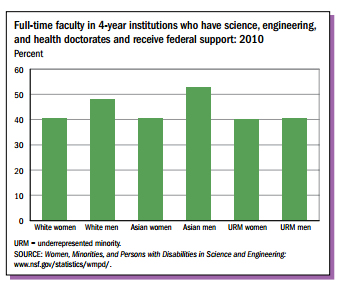

Further, Asian American women who make it to a faculty position find greater difficulty building their careers in that position. Unlike Asian American men, Asian American female full-time faculty position holders are less likely to be able to achieve and maintain federal funding (which is the primary source of funding for STEM researchers). By contrast, Asian American men are most likely of all groups to obtain funding.

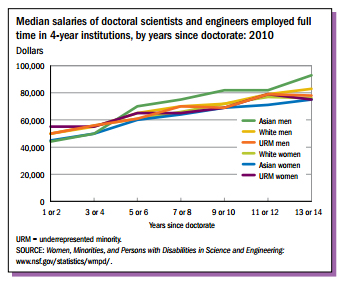

And, because the greater disadvantages faced by Asian American women (and other women) in career advancement in STEM, women of all races, including Asian American women, have the lowest median income relative to post-graduate years of experience compared to their male counterparts.

Summary

What does this tell us? Well, being a woman — including being an Asian American woman — confers significant disadvantages towards obtaining a post-secondary education and achieving in a highly-skilled job market like STEM. Women, including Asian American women, are more likely to be starting out of poverty and therefore have less access to education than men.

Those women who have access to education are able to enter and matriculate through college roughly as equally well as their male counterparts (thanks Title IX!). But, by about 13 years after degree conferment, women of all races, including Asian American women, are either more likely to be unemployed and/or are far less advanced in their careers (and earning between $10,000 and $20,000 less) than their male counterparts if they are in STEM.

There are many reasons for this achievement gap. One reason is that STEM fields are largely incompatible with starting a family. If one is in a tenure-track position, for example, tenure packages are due at roughly the same time that most women are in their early to mid thirties and ready to start a family (and indeed are biologically running out of time to do so). And while some universities have recognized this problem by beginning to offer comprehensive daycare, paternal leave, and the chance to stop the “tenure clock” for a year following the birth of a child, these institutional changes are slow to permeate the STEM field. The consequence, therefore, is that starting a family is professionally punitive to female scientists, whereas it is not for male scientists (and in particular Asian American male scientists).

An additional reason — one that is difficult to quantify by labour numbers — is the persistent dominance of men in STEM fields. Roughly 72% of workers in STEM are men, which often results in an entrenched “bro culture” that is highly intolerant of female co-workers. Consider, for example, this year’s many reports of publicly sexist remarks made by men in STEM: this article explores, for example, latent sexism among video game programmers. Such publicly sexist remarks only occur in an industry where similar remarks made in private are tolerated. And indeed, many women scientists can attest to the ongoing scientific “frat boy” mentality that permits the casual rape joke at work, or the snide treatment of female peers as either less intellectually rigorous and/or as if they are support staff. These attitudes are a strong deterrent to women in STEM.

Ultimately, institutionalized sexism is often difficult to parse. Certainly, one must keep in mind the economic privilege of all men and women who can benefit from an education and a job in STEM. However, my feminism argues that unequal treatment of women — at all levels of our society — is unacceptable, and that any obstacle towards advancement warrants attention.

And these data are a clear indication to me that there’s a conversation worth having about disadvantages Asian American women — and women of other races — continue to face in the workplace.