Call it #FOTBFever. Call it #Huangsanity.

Last night, the hotly-anticipated new ABC single-camera sitcom, Fresh Off The Boat, debuted in a special preview event: the series’ first two episodes aired in a bookend fashion around ABC’s Wednesday night anchor show, Modern Family (displacing for one week Anthony Anderson’s Black-ish); despite its clunky interrupted format, FOTB earned a solid 2.5 rating in the 18-49 demographic making it the second highest ranked comedy premiere this season and attracting better ratings than the most recent episode of Black-ish.

This marks the first time in 20 years that a primetime family sitcom has aired starring an all Asian American family, which is itself an historic occasion for the normalization of the Asian American nuclear family. That impact on the American pop culture (and political) zeitgeist cannot be — and should not be — understated.

However, in an effort to correct a few over-exuberant headlines and tweets of the past week, let’s also be clear: FOTB is not the first Asian American family sitcom; not the first sitcom to star an Asian American male lead; not the only primetime comedy or sitcom to star an Asian American; not the only currently airing primetime network show to star primarily Asian American actors and to delve deeply into questions of Asian American identity; and — since multiracial Asian Americans are still Asian American — not the only sitcom of the last two decades to focus a lens on a diasporically Asian American family.

Nonetheless, Fresh Off The Boat deserves kudos for being one of the few primetime shows — of any genre — to engage Asian American creative talent at all levels of production: inspired by the autobiography of a Taiwanese American celebrity chef, the show also boasts an Asian American producer, writers, and lead cast. For this reason, FOTB‘s voice (unlike that of many of its predecessors) rings clear as undeniably Asian American, and therefore marks a pioneering moment for the representation of an Asian American lived experience in mainstream television.

For this reason, Asian Americans could not have been filled with greater glee (and a healthy dose of trepidation) yesterday had Jeremy Lin single-handedly led the Lakers to a flawless victory over the Heat while announcing during the game’s halftime show his secret engagement to Taylor Swift below a stadium-cam HBO simulcast of Manny Pacquiao defeating Floyd Mayweather by total knockout victory in the second minute of round 2. All day, my social media timelines were a deluge of breathlessly excited status updates and tweets over FOTB; and, by the second episode’s closing credits last night at 10pm EST, viewers had crowded into live watch parties across the country to watch the series’ launch with over a thousand of their closest friends, and the hashtag #FreshOffTheBoat was a top trending topic on Twitter.

So, was it worth all the hype?

Unlike most of my fellow bloggers, I did not have the opportunity to preview Fresh Off The Boat prior to last night’s preview event. So, other than the promo ads that have been running since last year, I had no idea what FOTB was going to be like, and was awaiting yesterday’s launch to get my first taste of the show. So, like most of you, I sat down at 8:30pm EST last night and joined the #FreshOffTheBoat live-tweeting happening (Storify of my tweets are here).

Full disclosure: about halfway through episode two, I got called away to deal with my very own real-life — absolutely not fun or funny — Asian American family drama. So, I’m writing this review having sadly missed the latter half of episode two. Unfortunately, Jeff Yang (@originalspin) — father of FOTB star Hudson Yang, who plays young Eddie — says episode two was one of the strongest of the season; yes, I do plan on going back to catch up on what I missed.

As with most pilot episodes, FOTB‘s premiere episode was promising but clearly rough around the edges. Consistent with the genre format, episode one preoccupies itself with establishing the context of the show: adolescent Eddie (Hudson Yang) is a blase and rap-obsessed self-described “black sheep of the family” — incidentally not a charming line when paired with Eddie’s incessant use of hip hop culture and imagery — and is uprooted from DC’s suburbs and relocated by his parents Louis (Randall Park) and Jessica (Constance Wu) to Orlando, Florida, where the Huangs move into an all-White neighbourhood and become the new owners of a failing steakhouse named Cattleman’s Ranch.

The pilot offers a flavour of the series to come: a self-derogatory, sometimes painfully awkward deep dive into questions of cultural assimilation as framed through the Asian American experience, and without shying away from the uncomfortable spectre of race and racism. This focus is, again, a welcome and refreshing sea change as compared to the largely post-racial world inhabited by most of primetime’s Asian Americans. Unlike most contemporary shows, FOTB is willing to be edgy. From the choice of its show title to its range of topics, FOTB acknowledges and confronts the topic of identity head-on with its central question, “what does it mean to ‘fit in’ as American?”

The pilot opens the conversation with an inspired storyline centred around Eddie’s disappointment with the home-packed Asian lunchbox his mother has prepared for him. Faced with ostracism from the predominantly White cool kids in his school’s cafeteria, Eddie delivers a dinnertime ultimatum — he demands Lunchables. I appreciated FOTB‘s choice to filter this story through the metaphor of Lunchables, which hits all the right nostalgic notes for the Asian American mid-90’s kid (like me) while also offering some metatextual commentary: Eddie believes that by fitting a flavourless lunch into homogenous, indistinct, mass manufactured plastic squares, he can similarly fit his identity into those same boxes.

However, the pilot stumbles with the latter half of the episode, when Eddie — eagerly clutching his hard-won pizza Lunchables — is confronted by an angry Black classmate (Walter, played by Prophet Bolden) who inexplicably decides to bully Eddie by calling him a “chink” after having earlier refused to eat together. This is Eddie Huang’s lived experience and is documented in his memoir by the show’s same name, but it honestly makes for poor television writing: Why is Walter picking on Eddie? Why does he pick that moment to confront Eddie in front of the school’s (equally inexplicable) microwave? Why does he choose to call Eddie a slur? We can certainly imagine a host of completely plausible reasons for Walter’s behaviour, but all of this is us projecting our own politics onto an incident that offers no innate explanation. Furthermore, this plot point is left largely unresolved, despite some incongruous moralizing by the adult Eddie Huang in a voice-over about assimilation. Thus, even though the confrontation with Walter facilitates a hilarious scene about the stereotype of the overly-litigious Asian parent, this intensely controversial incident ends up feeling very much like a narrative afterthought and deus ex machina.

This issue of occasionally questionable writing choices extends into episode two, even though the script is definitely far more streamlined than with the pilot. Episode two juxtaposes two intertwining storylines: Jessica and Louis’ conflict over management styles at the restaurant with Jessica’s decision to give extra home-homework (in the style of a Kumon parody) to the kids. The writing feels much more polished in this sophomore outing despite the persistence of a few unfortunate lines, most notably Eddie’s bizarre quip — “does the yellow man like dumplings?” during a pick-up game — which I found neither funny nor shocking, and instead oddly forced.

Yet, the script’s occasional rough patches are far less distracting in episode two than in the pilot because here the show’s writing is almost entirely salvaged by the phenomenal acting cojones of Randall Park and Constance Wu. Although both were saddled with terrible faux Asian accents in the pilot (both actors normally speak in unaccented English), these hobbles were removed by the second episode allowing both actors to let their undeniable comedic timing to shine. I caught a gut-bustingly funny-awkward scene between Russell Park and his Cattleman’s Ranch employee, Mitch, who wants nothing more than to have the freedom to snack on croutons while being soothed by the close embrace of a “matronly woman with chubby arms”. My feed tells me that later in the episode, Constance Wu hits a homerun in a scene about a blooming onion. Even in the pilot, I found myself chuckling over Wu’s increasingly distressed Jessica, who is painfully unenthusiastic about Florida’s inescapable Whiteness, its lack of economic prospects, and its hair-wrecking humidity.

Two episodes in, FOTB is navigating between what I’ll dub “Asian American bingo” — the urge to touch upon conventional Asian American identity tropes (weird lunches, weird names, English fluency, high-expectations Asian parents) — and the originality with which it puts a “fresh” (see what I did there?) spin on these arguably cliched storylines. With its first two episodes, FOTB has successfully intrigued me with its boldness, and I’m curious to see what happens when the show ventures off the Asian American bingo card and into uncharted racial and cultural territory.

That being said, there are also some lingering concerns I have with FOTB that the first two episodes did little to alleviate. Going into the series, I was concerned about the appropriation of hip hop culture and its depiction of Asian American women, both issues that the real-life Eddie Huang already contends with in regard to his celebrity persona; my qualms remain after watching both episodes. From the pilot’s opening scene showing Eddie peacocking while decked out in gold chains and jerseys, to the scene where Eddie struts into the kitchen to the sounds of Snoop Dogg blaring from a boombox on his grandmother’s lap, I’m reminded: there’s a fine line between “homage” and “caricature”, as Asian Americans know all too well with regard to others who misappropriate aspects of Asian culture. I yearn for the show to address this dynamic with regard to Eddie’s love of hip hop, and how this might intersect with issues of Blackness and anti-Blackness, with greater nuance. Similarly, I wonder about the weight placed upon Constance Wu to serve as the show’s lone representation of an English-speaking Asian American woman. Although Wu’s Jessica is obviously a fierce and no-nonsense Asian American woman and mother, young Eddie Huang’s offhand quip calling his mother a “trick” in episode two — which went basically unanswered — was worrisome.

These criticisms are not intended to pan the show, or indeed to hold FOTB to the impossible standard of being all things to all people, even to all Asian American people. Instead, it is to recognize that FOTB is important, imperfections and all; indeed, the mark of our community’s arrival will not be the uncritical support we give a show because it is Asian American, but when sufficiently diverse programming exists within Asian American media that we have the freedom to shine a (constructively) critical lens on shows because no single show is forced into the corner of representing the totality of Asian America.

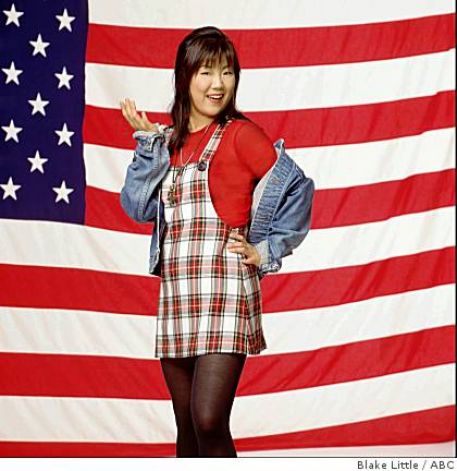

As Sean Miura recently wrote with sophistication, for too long our community has had only a handful of shows that reflect us, and this has crippled the Asian American media landscape. Margaret Cho’s All-American Girl suffered from this unrealistic expectation; we would do well not to penalize FOTB in the same way, especially not before the series has even cast off from dock. Whether or not FOTB ultimately manages to broaden its treatment of female and feminist identity, or adds sophistication to its depiction of interracial interaction, we must commit ourselves now to recognize that FOTB is not the sum total of the Asian American experience; it is instead one small slice of the Asian (and particularly East Asian) American experience. Sean said it better than I:

Our obsession with authenticity and our need to see ourselves will, perhaps, be our biggest tests in the coming weeks. This time around we have hindsight and can remind ourselves that though this story is in many ways one Asian American story, Fresh Off The Boat is ultimately not the story of Asian America; it is the story of Eddie Huang as told by the American Broadcasting Company. As hungry as we are to see our stories told, we must concede that this is not our own lived journey but rather one filtered experience in the ocean of Asian America.

FOTB sates Asian America’s hunger to see ourselves in media, and I certainly see a lot of my own childhood in the show. Whether or not the show has cross-cultural appeal — Twitter says, ‘yes’, but SnoopyJenkins was unconvinced — remains unclear, but I was surprised by how unusual, and refreshing, it was to watch a show that was both largely about me and also largely for me.

Nonetheless, I hope that going forward FOTB is treated as an appetizer, and not the full four-course meal. Because, as much as FOTB speaks to me, there are many members of Asian America who still find little of themselves in FOTB. Even with FOTB on air, mainstream TV lacks any compelling conversation on South Asian American or Muslim identity, on Southeast Asian American identity, or on the identity of our Pacific Islander allies. This does not mean that we should criticize, or torpedo, FOTB for not representing each and every one of us. Instead, even as we celebrate FOTB and the milestone it represents in bringing one version of our stories to the mainstream, we must not let up our demand for more.

Asian Americans are an exceedingly connected, and rapidly expanding, fraction of digital media consumers. Most of us watch an inordinate amount of TV, spend an inordinate amount of our time gaming, and ‘like’ an inordinate amount of things. The fervor with which our community rallied behind FOTB last night is ample demonstration of our thus-far-ignored consumer power, and how we are starved for Asian American programming.

So yes, I will be watching FOTB this season: already, the show is a welcome and refreshing addition to the national conversation over what it means to be Asian American that I hope will succeed, supported in no small part by our community’s many loyal eyeballs and spending dollars. I hope that FOTB‘s success this spring television season will be all the proof we need that Asian Americans are in the midst of a famine: we want — no, we need — more, and importantly more diverse, Asian American shows built by the efforts of Asian American creative talent; and, we want it now.

I hope that the success of FOTB‘s premiere can one day be remembered as the watershed moment that invites a new era of diverse Asian American programming that can begin to reflect the “ocean” of the Asian American experience.

If you missed last night’s preview event, both episodes will be available on demand. Fresh Off The Boat will return with the third and fourth episodes of the series in its normal timeslot on Tuesdays at 8pm starting February 10th. (Corrected)