Middle-class families imagine their stereotypical dinner-time routine as an intimate setting when parents and children might gather over a hearty meal to share funny stories of the day; for mine, as (I suspect) many others, dinner-time conversation is too awkward to be fun. I didn’t care about workplace politics. My parents weren’t concerned about my classroom gossip. Here’s my confession: we really didn’t have much to talk about. Instead, for my family (as I suspect it was for many others), our family-time was watching our favourite family sitcoms over dinner. In some ways, we were inviting the characters of those shows into our lives, to become part of our families, to replace our own (boring) dinner conversation with their (hilarious) adventures.

Since the 1940’s and 1950’s, the American family sitcom has presented an idealized version of the American middle-class family: a nuclear (or oddball) family, facing obstacles with a grin and overcoming them with reaffirmations of love.

Not surprising, therefore, that these images — from Full House and Family Ties and Boy Meets World — are inextricably linked to my generation’s definitions of love, family and Americana. And, from its inception, the sitcom has also been a covertly political tool, pushing our definitions of those very same concepts.

I Love Lucy undisputedly revolutionized the sitcom genre, introducing for the first time the notion of multi-camera shooting that is now standard practice for most sitcom filming. But, I Love Lucy is also remarkable for focusing on the antics of two characters in an interracial (or at least intercultural) marriage, at a time before Loving v Virginia when such a pairing might be considered to be at the very least unconventional. It can be argued that the popularity of I Love Lucy in the face of the show’s full embrace of the Cuban heritage of Ricky Ricardo (played by Desi Arnaz) contributed to America’s changing attitudes towards interracial couples in the late 1950’s: America’s favourite couple of the decade was inter-ethnic.

Since that time, the genre has continued to push the boundaries in redefining the American family, and in so doing normalize the diversity of the American familial experience. Married with Children served as an anti-thesis to the Leave It To Beaver utopia of the 1950’s; for better or worse, this sitcom (like others of its ilk) broadened the idea of the (White) American family by suggesting it was okay to be dysfunctional.

Meanwhile, The Cosby Show took a different tactic: it presented for one of the first times on television an upper middle-class African American family that directly contradicted television’s long-standing notion that the American nuclear family was synonymous with Whiteness, while also refusing to write a show that explicitly focused on race and race relations. Instead, Bill Cosby’s pioneering sitcom asserted a heart-warming middle-class Black experience that was anything but dysfunctional, with episodes focusing on issues that seemingly transcended race, such as dyslexia and teen pregnancy.

The widespread popularity of Cosby Show, as well as its successors Family Matters and Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, for viewers of all racial backgrounds speak to their influence in normalizing the nuclear Black family. These shows asserted that the the American family was comprised of African Americans too, and that the concepts central to the American family sitcom genre — the bonds of love, caring and devotion — are not specific to Whiteness; they are universal.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GmerFuzRNZ4

(Note: Family Matters and Fresh Prince were two of my favourite sitcoms as a kid. I dare you to not watch the above scene and still have a dry eye at the end.)

Twenty years ago, Margaret Cho made history as the creator and star of All-American Girl, America’s second sitcom to star an Asian American character, and the first to feature a predominantly Asian American cast. (The first sitcom to star an Asian American actor was the short-lived Mr. T and Tina which starred Pat Morita and ran for a single season in 1976).

All-American Girl highlights the life of Margaret Kim, a progressive twenty-three year old Korean American woman living with her more conservative and traditional family. The show, which ran from 1994-1995 is noteworthy for being the first Asian American sitcom to offer a modestly in-depth exploration of the Asian American experience, focusing its narrative squarely on the dynamics of protagonist Margaret’s hyphenated identity and her interaction with her more traditional mother (played by Jodi Long). From the series’ name to its ambitious subject matter, All-American Girl promised to challenge the stereotype of the perpetually foreign Asian American with the undeniable counter-assertion of a Korean all-American woman and her family.

Despite early excitement, All-American Girl received mixed reviews and mediocre ratings; to some extent, the show became a victim of its own pioneering status. Wrote Philip Chung for the LA Times in 1994:

Yes, the show could be improved. Yes, I often cringe when I hear the actors attempt to speak Korean. Yes, some of the cultural references are confusing. But there’s much about the show that is cause for joy.

The most incredible thing about the series is that it even exists. As anyone working in the television industry will tell you, it’s nearly impossible to get a program on prime-time network television. The fact that a show revolving around an Asian American family is on the air is phenomenal.

Much of the continuing criticism surrounding the program seems to be coming from people who feel “All- American Girl” doesn’t match their vision of what a Korean or Asian American show is. What we need to understand is that this is only one program and, therefore, cannot possibly be all things to all people.

Chung’s words do not diminish the Asian American community’s valid concerns — did it cross the line into caricature? — over the show. However, Chung’s words also emphasize the ongoing need for shows that aspire to be All-American Girl in the face of the continuing underrepresentation of Asian Americans on primetime television in general — we are between 1-3% of characters on primetime TV — and in the sitcom genre in particular.

Twenty years after the cancellation of All-American Girl in 1995, there remains a dearth of Asian Americans in American sitcoms. For the most part, Asian Americans appear as (often racially stereotypical) secondary or recurring characters — Big Bang Theory’s Raj, 2 Broke Girls’ Han Lee, Community‘s Ben Chang, Dads’ Veronica — with only two contemporary sitcoms featuring Asian Americans in principle or leading roles.

In 2012, Mindy Kaling made headlines as the first South Asian woman, and second Asian American woman, to star in a primetime TV sitcom — The Mindy Project — and the show has since enjoyed strong ratings and has catapulted Kaling to A-list status. The show focuses on a late twenties/early thirties OB/GYN who tries to balance her professional life with her search for romance. The show has been rightfully heralded as ground-breaking and feminist in its portrayal of the South Asian American protagonist Mindy Lahri. However, Mindy Project has also chosen not to focus broadly on Asian American family dynamics, and stars only a handful of Asian American characters — virtually none regulars — alongside Kaling.

Nonetheless, the fact that between 4 – 5 million viewers tune in to watch the comedic antics of an Asian American woman every week proves the viability of the Asian American sitcom. Yet Mindy Project still stands virtually alone in the primetime TV sitcom landscape.

In fact, the only current family sitcom to star an Asian American is Sullivan & Son, which also debuted in 2012, and which (unlike Mindy Project) has suffered mixed to negative reviews for all of its time on the air. Starring Steve Byrne as Steve Sullivan, the show focuses on Sullivan’s relationship with his Irish American father and Korean American mother (played by Jodi Long, formerly Margaret Cho’s mother in All-American Girl). Protagonist Steve Sullivan’s identity as a biracial Asian American is only a minimal part of the show, and like Mindy Project, it does not feature a predominantly Asian American cast.

Thus, despite the fact that Asian Americans are the fastest growing racial population in the country, and are avid consumers of primetime television (according to Neilsen, we watch about 100 hours a month on average, favouring variety shows like American Idol), there are still few primetime TV sitcoms that appeal to our viewership.

This week, ABC is in a position to change all that.

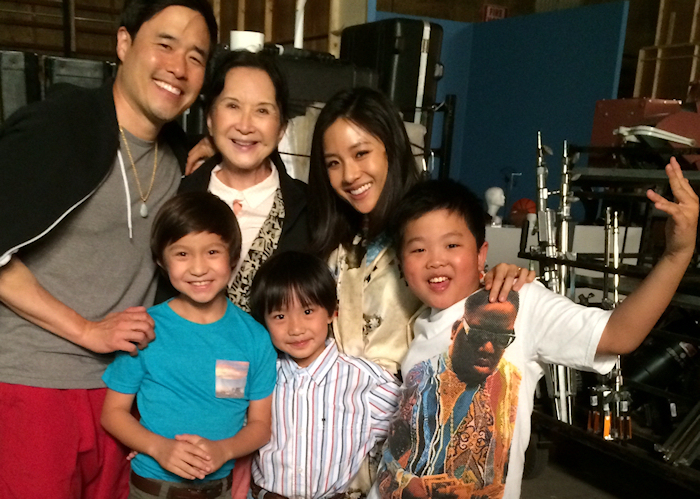

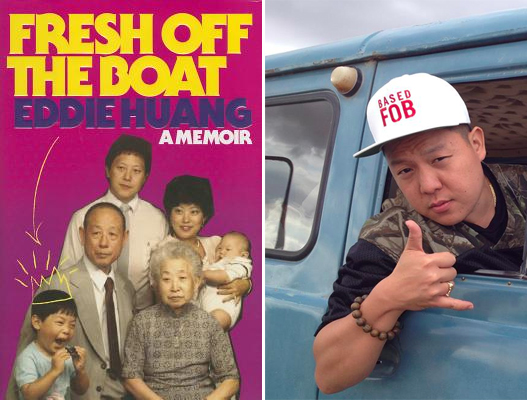

Recently, the network ordered a pilot for Fresh Off The Boat, a sitcom based on comedian Eddie Huang’s autobiographical book by the same name. The book-turned-sitcom would focus on Huang’s childhood moving from a racially diverse neighbourhood in Washington DC to a predominantly White neighbourhood in Orlando, and the culture shock that occurs therein. The pilot involves Asian Americans at every stage of production, including writer/producer Nahnatchka Khan (That B___ In Apartment 23) and stars a cast of Asian American actors as Huang’s family, including Wall Street Journal writer (and friend of this blog) Jeff Yang’s son Hudson in the lead role as a young Eddie Huang.

Now, let me first be clear: I don’t know Eddie Huang. I haven’t read Fresh Off the Boat, and I haven’t seen this pilot. I have no idea if this show is going to be any good.

But, it is a travesty that we have spent the last two decades with Asian Americans largely invisible in primetime television. Unlike Cosby Show, which ultimately pioneered a genre of African American family sitcoms, All-American Girl remains both the first and only sitcom to star a majority Asian American cast and to spotlight the Asian American familial experience. With Asian Americans still struggling under stereotypes as the Perpetual Foreigner and the Model Minority, our community could strongly benefit from not one but several Asian American family sitcoms that diversify and normalize the broad range of the Asian American experience.

Twenty years after All-American Girl, a show like Fresh Off The Boat as well as other sitcoms of its kind are long overdue. When only one or a handful of television shows and sitcoms are available that star Asian Americans, each show must as Chang wrote “be all things to all people”, an impossible task.

Fresh Off The Boat — by the strength of its ambition alone — is guaranteed to follow in the footsteps of All-American Girl and reassert the Asian American family as a fresh, new face for the American familial archetype. Furthermore, by bringing Fresh Off The Boat to television, we can start to break the trend of having only one or two Asian American sitcoms on TV at a time. This is a necessary first step if we are to create a genre of Asian American primetime cinema wherein each show has the freedom to speak to facets of the Asian American experience, and therefore not depend on any single show to speak for our community in its entirety.

This week, ABC is deciding the fate of Fresh Off The Boat based on the show’s pilot. Please join me in asking ABC (@ABCNetwork) to green-light this show by tweeting the network and sharing this post with the hashtag #FreshOffTheBoat.

Read also: We Need Asian American Family Sitcom “Fresh Off The Boat” (HapaMamaGrace)