For over 12 years, the internet has been an intellectual companion, and a forum wherein I have shaped my activist thought. Although I found my way to Asian American activism through offline work, it was my online activities that have been largely responsible for who I am as an Asian American activist today.

My earliest political opinions — and my commitment to the importance of debate in shaping political opinion — were forged on highly-active Asian American message boards like YellowWorld.org (edit: holy crap — it is still online and someone even posted something this year!), which served as social hubs for the Asian American community throughout the early 2000’s. Over the years, my Reappropriate blogging self became a digital alter-ego, and this blog served as a space for the exploration of Asian American social justice thought — both for myself and for others. Today, I feel hyphenated in more ways than one; not only do I exist with the hyphenated racial identity of an Asian American, but I also feel as if my fundamental sense of self has become a hybrid of my real-life and my online presence.

For me, the role of the internet as a tool for radical consciousness-building cannot be understated. I would not be who I am without access to this digital space, and the freedom to cultivate new (and oftentimes revolutionary) ideas.

Today, that freedom is being jeopardized. Today, we are on the brink of legislation that would shackle the internet, and in so doing, make it fundamentally less free.

Last week, I posted about the FCC’s pending decision on new regulations that will govern large internet providers; some of the options being weighed have profound implications for the fight over net neutrality (if you’re not up on what’s going on, the linked post contains a good recap). All of us who maintain a foot in the realm of the digital should be fearful of an unfree internet. All of us — bloggers, tweeps, redditors, instagrammers, pinners, tumblrers (?), and all-round social media addicts — should be rising up and taking a stand against a non-neutral internet.

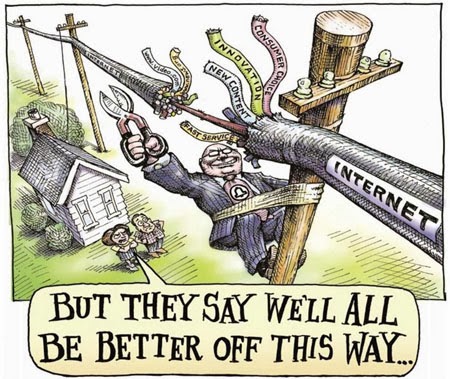

Right now, major cable companies including Comcast, AT&T, Time Warner and Verizon have spent over $75 million lobbying to deregulate broadband access, which ironically would have the net effect of making the internet less free. That is more than three times the money spent by pro-net neutrality lobbyists to protect a free internet. See, these big cable companies want to eliminate once and for all any government restrictions that would prevent them from disproportionately prioritizing the download of some content through their networks over others. These major cable companies want to make it easier to download some content which has paid for “fast lane” distribution; and consequently, make it harder to download content created by people — like myself — who can’t pay for “fast lane” access.

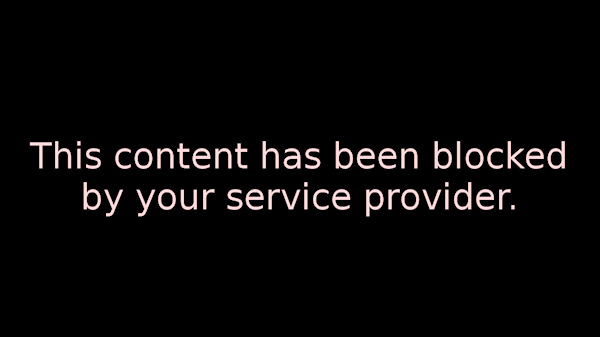

These major cable companies want to be the gatekeepers to your internet content. They want to decide which websites will work for you, and which ones aren’t worth efficient access to.

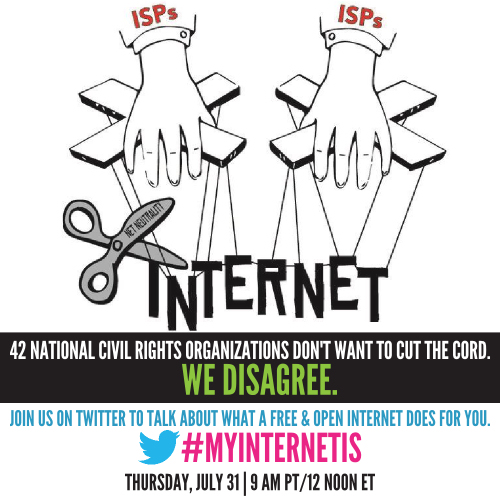

In a letter to the FCC, 42 civil rights organizations including some of Asian America’s largest, oldest and most prominent groups, joined their voices with the anti-net neutrality chorus coming of the nation’s biggest cable companies. Yet, in their letter to the 5-member FCC, the civil rights group coalition also made a compelling argument in favour of net neutrality, even if they didn’t realize it. In their letter, the coalition — National Minority Organizations — wrote about how broadband access is a civil right:

The National Minority Organizations recognize that access to broadband, adoption, and digital literacy are critical civil rights issues — broadband is essential to living a life of equal opportunity in the 21st century. Without broadband access, low income and middle-class Americans — and particularly people of color — cannot gain new skills, secure good jobs, obtain a quality education, participate in our civic dialogue, or obtain greater access to healthcare through telehealth technologies.

In today’s globalized and digitally connected world, internet access is critical for full political participation and citizenship. Classrooms across the country are now almost fully integrated with online spaces, and opportunities for academic self-improvement increase significantly with connectivity. For lower-income students — whether enrolled in post-secondary education or career specialization and training — distance learning options through online coursework greatly facilitate the pursuit of academic degrees when juggling full-time jobs and families. These days, even the employment marketplace has become fully digitized; jobseekers in today’s economy know that finding a position without steady internet access and an email account can be a significant obstacle. The healthcare marketplace established by the Affordable Care Act a few years ago is accessible predominantly through the internet. Internet access is clearly a necessary requirement for full citizenship in today’s America.

And, if internet access is itself a civil right, than consider how valuable our First Amendment rights to free, uncensored, speech on the internet must be.

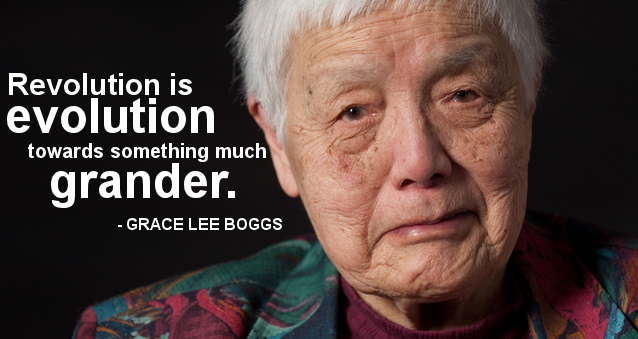

Last night, I had the chance to participate in a Twitter-watch party of American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs, a feature-length documentary film focused on the activism of Detroit-area civil rights hero Grace Lee Boggs. The evolution referenced in the film speaks to Boggs’ shift in her attitudes towards a more thoughtful and self-reflective activism. Throughout the last four decades, Boggs’ activism focused on cultivating spaces for the development of revolutionary thought in herself and her allies.

At one point in the film, Grace Lee Boggs says, “our ideas come out of conversation.” Elsewhere, she opines, “the radical movement has overemphasized the role of activism and underemphasized the role of reflection.” A champion of debate and dialogue, Boggs transformed her living room into a study center for radical thought.

Today, digital activists are transforming online spaces in the same way. Online activists are using the internet to make connections with one another that defy hegemonic institutions of oppression, and that are amplifying historically silenced voices. We are circumventing traditional systems of power and empowering the grassroots. We are creating spaces to challenge institutions of privilege, and motivating digital citizens to break through their own boundaries of thought. The revolution will not be televised, but it very well might be (at least in part) digitized.

Last night’s Twitter-watch party perfectly exemplifies the power of the internet as a radical tool for reflective activism. Ten years ago, the internet helped connect filmmaker Grace Lee (@anothergracelee) with a revolutionary icon in Grace Lee Boggs (@GraceLeeBoggs). Upon completion, American Revolutionary has been available for online streaming — for free — through PBS all-month, and last night, Asian American digital activists (including myself) separated by geographic distance nonetheless came together in Twitterspace to learn more about the philosophy of a powerful woman like Boggs, and to share her ideas with the digital world.

This is the kind of content — radical, subversive, interactive, and grassroots — that would be displaced in a non-neutral internet where major internet providers get to decide which content is worth sharing. This is the kind of content that major cable companies would functionally censor through their prioritization of paid premium content over unpaid and informal exchange of ideas. Yet, this is also exactly the kind of social justice content that most powerfully symbolizes the essential role of the internet in activism, education, and civic participation.

As the National Minority Organizations coalition notes, minority communities enjoy high rates of broadband access. Nearly three-quarters of African Americans and Latinos access the internet through their mobile devices, and Asian Americans are the most-connected group in America (as well as the most active of online consumers). Yet, broadband access remains spotty, particularly among lower-income and rural Americans; the wealth gap is larger among minorities (including Asian Americans), with a significant population of our communities living below the poverty line. In addition, the economically underprivileged (many of whom are people of colour) are significantly more likely to access the internet primarily through their cellphones, which compromises the degree to which certain aspects of the internet are accessible and available — not only are such users limited by their data plans, cellphone interfaces can (through hardware considerations alone) hamper the degree to which users participate in long-form civic discussion, or generate their own long-form content. As the world moves digital, could existing structural iniquities in access coupled with an unfree internet create a new form of political disenfranchisement, a form of cyber-redlining?

So much of how we interact with one another requires full and unfettered cyber-access. We are becoming a nation of cyborgs — people with both online and offline presences. In such a digitally-connected society, the internet is not just a privilege; full access to a free, neutral internet and associated digital citizenship must be considered a civil right for all.

And if the lived histories of powerful Civil Rights-era heroes like Grace Lee Boggs teaches us nothing else, it teaches us that respect for basic civil rights does not come naturally to an unregulated marketplace; civil rights must be fought for and guaranteed through government protection. Net neutrality is a radical necessity.

Today at 12pm EST/9am PST, Asian American activists including myself (@reappropriate), Juliet Shen (@Juliet_Shen) of Fascinasians, Vanessa Teck (@VanessaTeck) of ProjectAVA, and the organizers of 18MillionRising (@cayden, @samala, @pakouher) are hosting a Twitter conversation about the importance of net neutrality at #MyInternetIs. Please join us!