Last Friday, filmmaker Justin Chon’s latest – Blue Bayou – opened in theatres nationwide, and I interviewed Chon as well as actor Linh-Dan Pham about the film. Shortly after the film’s release, however, members of the adoptee community took to social media to express frustration about Blue Bayou and the ways in which they feel the film fails to properly represent the adoptee experience.

Korean American adoptee and abuse survivor Adam Crapser – who was deported to South Korea five years ago and whose story I wrote about several times on this site – posted a statement on social media saying that Chon reached out to him four years ago expressing interest in bringing his story to film, but that communication suddenly ceased after Chon responded. Crapser was deported in 2016 following an intense grassroots effort to stop his deportation proceedings, leading to separation of him from his wife and young children.

I’m a real person. I’m not a Hollywood character made for profit, award-seeking, or tear-jerking movies.

Adam Crapser

According to a posted screenshot of an early text message between Chon and Crapser, Chon says he learned of Crapser’s story through a Vice article.

“I feel like everyone in the US should know what happened to you because it’s ridiculous,” says Chon in the text exchange. Indeed, Blue Bayou‘s protagonist – Antonio LeBlanc – bears striking resemblance to Crapser.

Crapser says that Blue Bayou is based on his story but that he did not give permission for the use of his story in the movie, and that neither he nor other deported adoptees were consulted during the making of the film. (In his interview with me, Chon said that he worked with five adoptees in developing the film’s script, but he did not mention if any were facing deportation.) Crapser is not included in the film’s end cards acknowledging other adoptees who have been deported or who currently face deportation.

Advocacy group Adoptees for Justice says that Blue Bayou exploits adoptees like Crapser.

“The film Blue Bayou is clearly based on the life of Korean American adoptee Adam Crapser, who did not give the filmmakers his consent or the rights to his story,” says Adoptees for Justice in a public statement. “Adoptees for Justice cannot tolerate the appropriation of our community members’ stories and lived experiences. Given all that we lose as intercountry adoptees, we should not also lose the right to and control of our own stories.”

“I’m a real person. I’m not a Hollywood character made for profit, award-seeking, or tear-jerking movies,” adds Crapser on social media. Crapser further says that the production team behind Blue Bayou added insult to injury when they eventually contacted him in 2020 asking for a picture of him with his adoptive family. Crapser has openly discussed the abuse and torture he endured at the hands of his adoptive parents, who both served jail sentences in plea deals following charges of physical and sexual abuse committed against their adopted and foster children.

Stephanie Drenka is Communications Director for Dallas Truth, Racial Healing, & Transformation and a Korean American adoptee. She says that she was initially “cautiously optimistic” about Blue Bayou. But after Crapser and other adoptees posted their stories on social media, she now plans to join calls to boycott the film. In addition to Crapser not having been able to be fully involved in the film’s production, Drenka is frustrated that an adoptee wasn’t cast to play Blue Bayou‘s protagonist, Antonio LeBlanc. She sees Blue Bayou as yet another example of adoptees’ voices and experiences being overlooked or erased, even within progressive Asian American circles.

“Adoptee voices are often silenced in our own personal lives as well as at a systemic level,” says Drenka, who cites studies showing that suicide attempts among adoptees is four times that of non-adoptees. “Our stories are exploited by adoptive families, the adoption industry, people on both sides of the abortion debate, and others. Reclaiming our stories – and choosing when, how, and if to tell them – is one of the very few ways in which we have some agency as adoptees.”

Reclaiming our stories – and choosing when, how, and if to tell them – is one of the very few ways in which we have some agency as adoptees.

Stephanie Drenka

When reached for comment on this story, the Blue Bayou team referred to online postings on social media wherein adoptees have said they felt reflected in the film’s protagonist and subject matter.

“I’m 44 years old, and I’m reasonably sure tonight is the first time in my life I’ve seen a character in a movie who is also a Korean adoptee,” says Instagram user Travis J Cross in a posted Story referred to Reappropriate. “Thanks to Justin Chon for beautifully, thoughtfully, and sensitively telling a complex story – on the big screen – that resonates in powerful ways with my heritage and history.”

Drenka, however, would like for Chon and Blue Bayou‘s production team to fully acknowledge the harm they have caused Crapser and the adoptee community, and to invest in creating a space for adoptees to engage with them in dialogue and healing. She and adoptee advocates would like for Blue Bayou – and the rest of the Asian American community – to actively engage in the fight to implement policy changes that would protect adult adoptees from deportation, as well as other measures to reform the adoption system in this country and worldwide.

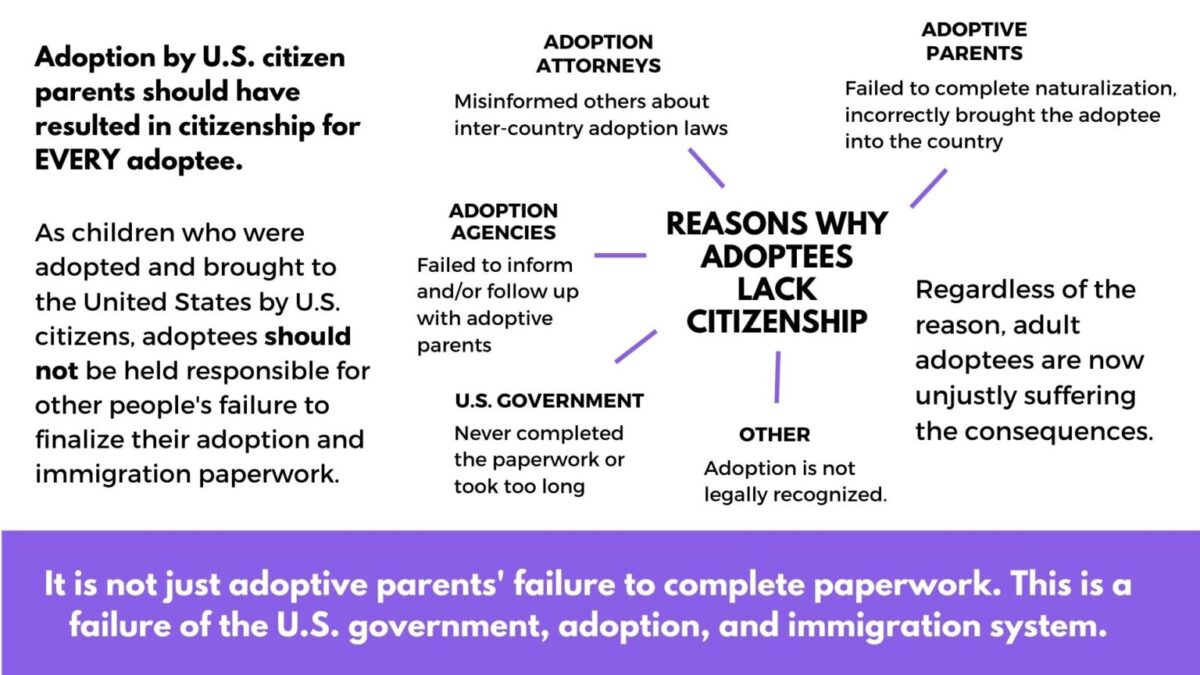

One such effort is the Adoptee Citizenship Act of 2021 (HR1593 / S967) which would directly address adult adoptees who were left unprotected by the Child Citizenship Act of 2000 – the very loophole that allowed for Crapser’s deportation and that is the subject of Blue Bayou.

“Congress has the chance to carry through on promises made to adoptees that this country is our home, too. All they have to do is pass the Adoptee Citizenship Act,” wrote Olivia Zalecki last year in a guest essay for Reappropriate. Zalecki is a transnational adoptee and a member of Adoptees For Justice.

The Adoptee Citizenship Act was introduced in Congress in March by Representative Adam Smith (D-Washington), but it needs political support to ensure its passage. Adoptees for Justice asks that the community immediately get involved in the fight to pass the Adoptee Citizenship Act by urging members of Congress to cosponsor the bill – an effort that adoptees say Chon and Blue Bayou should have gotten engaged in long before the film’s release.

“Chon could have de-centered himself and cast an adoptee in the leading role,” says Drenka. “The Blue Bayou marketing and public relations team should have used their resources and platform to amplify a call-to-action about supporting the Adoptee Citizenship Act, educated the community about issues in transracial adoption, or shared messages from actual adoptee activists.”

In their statement, Adoptees for Justice urges community members to sign the petition calling for a boycott of Blue Bayou until the film’s production team contacts Crapser and addresses the concerns raised by the adoptee community.

This continues to be a developing story and this post will continue to be updated with new developments.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misstated the year of Crapser’s deportation. It was 2016, not 2015. In addition, Chon reached out to Crapser but didn’t respond back after Crapser responded. They did not exchange multiple messages as an earlier version of this post suggested. We regret these errors.

Update (9/21/21): This post was updated to include social media postings that Reappropriate was referred to by the Blue Bayou team following a request for comment on this story.