By Guest Contributor: Kong Pheng Pha

Conversations have proliferated on social media debating Hmong Americans’ position in the ongoing racial conflicts in the U.S. The murder of George Floyd at the hands of four Minneapolis police officers, one of them a Hmong American, warrants a reflection on the place of Hmong Americans in the revolution.

A New York Times article by Sabrina Tavernise attempted to examine the position of Hmong Americans in the murder of George Floyd. The article tried to present a balanced view of where Hmong Americans are situated in this ongoing revolution without fully putting Hmong Americans on either “side” of the conflict. However, this concerted effort to present ‘two sides’ fails to reflect where many Hmong Americans are: we want police to be held accountable for Floyd’s murder as much as any other community who possess any sense of equality and justice.

This concerted effort to present ‘two sides’ fails to reflect where many Hmong Americans are: we want police to be held accountable for Floyd’s murder as much as any other community who possess any sense of equality and justice.

Hmong Americans are often painted as refugees that are simply “caught up” in America’s racial conflicts. For example, the New York Times article by Tavernise was inaccurately titled “They Fled Asia as Refugees. Now They Are Caught in the Middle of Minneapolis.” The printed version of the article has a different headline, although it is not any better: “Hmong-Americans Find Themselves in Middle of Twin Cities Uproar.” Both framings do a disservice to Hmong Americans and their place in American history and society. We are not passive bystanders, “caught up” in a racial justice movement that doesn’t actually impact us: we are also stakeholders in this fight, particularly in Minnesota — home to the largest Hmong American population per capita in the country.

Hmong Americans entered the U.S. as refugees, but many carefully considered their decisions to migrate to the U.S. as they languished in Thailand’s refugee camps after the U.S. retreated from Laos in 1975. Refugees are often seen as people without agency, yet Hmong Americans understood how horrible people of color are treated in this country, and they weighed those facts in choosing to migrate to the U.S.

Moreover, Hmong Americans have been active agents in fighting racism in this country since our arrival. Hmong Americans are not passive refugees, we are also stakeholders in the ways racism enacts violence against people of color. While our experiences as refugees are not equivalent to the brutality of anti-black racism experienced by Black folks, our and other Southeast Asian American communities have also experienced other forms of racism since our arrival, ranging from taunting and threats from our neighbors, to active xenophobic violence and deportations, to murder at the hands of police. The same New York Times article by Tavernise brings up the unjust killing of Hmong American teenager Fong Lee at the hands of a Minneapolis police officer. What is missing from that story is how Fong Lee’s murder galvanized a generation of Hmong Americans to fight for racial justice. Hmong Americans have organized against racist radio stations that paint our cultures and people as primitive and barbaric simply because our ways of life do not align with that of the dominant culture. The claim that Hmong are “caught” in the whirlwind of America’s racial conflicts negates the agency of Hmong Americans to actively fight against racism.

The claim that Hmong are “caught” in the whirlwind of America’s racial conflicts negates the agency of Hmong Americans to actively fight against racism.

Hmong Americans, and Asian Americans as a larger racial group, are often positioned by white supremacy as a wedge between police and Black communities. In truth, there are Hmong Americans on both sides of this and other social and political issues — as would be expected of any community. Yet, the popular portrayal of Hmong Americans as passive people without agency in the current fight against white supremacy overlooks our reality. The group Hmong For Black Lives is a testament to how Hmong Americans are organizing to educate our own communities about the Movement for Black Lives. In just a matter of days, this multi-generational group have raised over $10,000 for the Black Lives Matter cause and successfully translated a variety of social justice language for native Hmong language speakers.

In Minnesota, attention — including within some circles of the Hmong American community — is focused on the destruction of Hmong American businesses and other small businesses in the aftermath of recent uprisings mostly along St. Paul’s University Ave . We need to take these conversations seriously but, we must avoid attributing the destruction of ethnic businesses to the “looting” of protesters. This line of thinking misses the point of economic instability and spatialized inequalities that ultimately made Hmong American and ethnic businesses on University Ave more susceptible to destruction during heightened conflicts in the first place. Additionally, it has been recently exposed that white provocateurs were also involved in destroying buildings and burning the 3rd precinct police station. Overall, we must be careful in how we think about the destruction of property in the Twin Cities. I truly empathize with the collateral damage incurred by some within the context of uprisings and revolutions, but we also cannot allow ourselves to fall into the trap of valuing property over human lives.

Another current theme I have witnessed within online discussions is the idea that the uprisings are threatening Hmong Americans and our “American dream.” Tavernise’s New York Times article surely played on this narrative, including in their headline. Many Hmong Americans — like most Americans — want a better life for themselves and their families, but we should challenge the reductive narrative of this ‘American Dream’ mythos. By even suggesting that the protests are sabotaging the livelihoods of Hmong Americans, we negate the fact that various other larger and more insidious factors, such as racism, lack of opportunities for education, and unequal distribution of capital — known as racial capitalism — work together to create extremely challenging conditions for working-class and refugee communities to become upwardly mobile.

Another topic of contention is the faulty generational framing of Hmong Americans in the Black Lives Matter movement. I have observed discussions that wrongly position young Hmong Americans as pro-Black Lives Matter, while our elders are portrayed as emphasizing their grievances over property loss. This flawed framework perpetuates the injurious “intergenerational gap” narrative that Hmong Americans have been fighting for decades. My work with Asians for Black Lives during the uprisings over the 2015 murder of Jamar Clark in North Minneapolis intimately involved our elders around racial justice and Black Lives Matter. This reductionist framework simplifies the complexity of our communities and erases the work that many activists have been doing to engage our elders in the Black Lives Matter Movement. We learned through our work with Asians for Black Lives that Hmong Americans (and Asian Americans of all ages) have diverse viewpoints, not easily reduced to an over-simplistic intergenerational misunderstanding.

[Hmong Americans] are not simply “caught up” in racial tensions and conflicts as a wedge, innocent bystanders, or a third-party community. We have fought, and we will continue to actively fight, for racial justice for our communities and work to forge deep solidarities with Black communities so that we can achieve justice for all people.

While this issue has catapulted Hmong Americans into the national spotlight, we are complex people who have intricate histories with our Black neighbors beyond what is traditionally reported about in mainstream media. We are not simply “caught up” in racial tensions and conflicts as a wedge, innocent bystanders, or a third-party community. We have fought, and we will continue to actively fight, for racial justice for our communities and work to forge deep solidarities with Black communities so that we can achieve justice for all people.

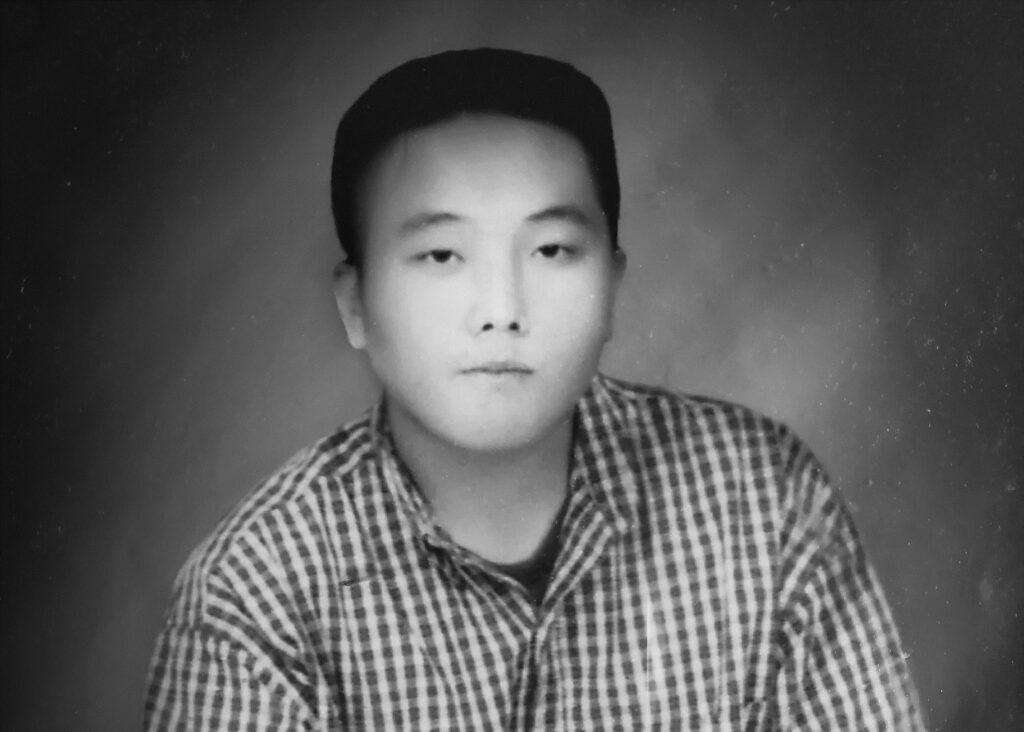

Kong Pheng Pha is an assistant professor of Critical Hmong Studies and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire where he teaches courses on social justice.

Learn more about Reappropriate’s guest writing program and submit your work here.