By Guest Contributor: Nicholas Wong

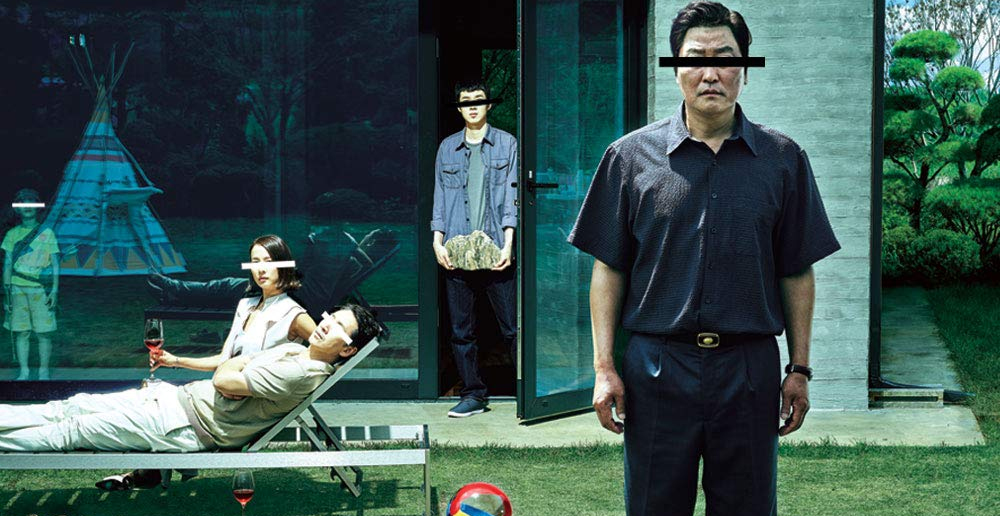

Last month, people around the world celebrated the underdog success of Korean film Parasite as it swept through the 92nd Academy Awards to win four Oscars. Each new award for the film ratcheted up a breathless excitement that culminated in a historic win for Best Picture, the first foreign-language film to ever take home that honour.

The victory was especially meaningful to Asian North Americans1Writing as I am from a Canadian context, I use the term “Asian North American” here to collectively refer to the broadly similar sociocultural categories of “Asian American” and “Asian Canadian”; however, I recognize that these categories warrant distinction under other analytical circumstances. , who took to social media in droves to express their pride in the film’s achievements. For decades, Asian North Americans have lamented the deplorable state of Asian representation in Western pop culture. In North American media, Asians have been either almost non-existent or, when portrayed, depicted through harmful racist stereotypes. In recent years, high-profile controversies surrounding films like Aloha and Ghost in the Shell – both of which featured the “whitewashing” of ostensibly Asian roles – have amplified the call for more Asian representation in Hollywood.

A positive shift in this cause has occurred over the past two years, with Asian-led films like Crazy Rich Asians, Always Be My Maybe, and The Farewell garnering box office success and critical acclaim. These films, all helmed by Asian directors and featuring Asian actors in starring roles, have been praised within the Asian North American community for proving the viability of Asians in pop culture, authentically portraying our experiences, and debunking stereotypes. Add on Parasite’s Best Picture win, and it would appear as though Asians have finally broken through Hollywood’s bamboo ceiling.

However, the reading of these films’ significance as primarily tied to their success in achieving Asian representation reveals a limited capacity for Asian North Americans to critically evaluate their own media. The perceived scarcity of – and consequent hunger for – Asian popular media representation has foreclosed the possibility of talking about our successes in anything but celebratory tones. “If we don’t support our own at all costs,” the thinking goes, “we may never get another chance.”

The perceived scarcity of – and consequent hunger for – Asian popular media representation has foreclosed the possibility of talking about our successes in anything but celebratory tones. “If we don’t support our own at all costs,” the thinking goes, “we may never get another chance.”

This “representAsian” discourse is fixated on the mere act of representation itself, with little regard for how these representations refute or uphold racial hierarchies. Thus emerged the unprecedented commitment of Asian Americans to support the financial success of Crazy Rich Asians, despite the film problematically trafficking in model minority stereotypes and colourism. Nora Lum, who starred in both Crazy Rich Asians and the aforementioned The Farewell, has been criticized for the way her “Awkwafina” persona relies on a stereotypical performance of “sassy” Black womanhood. Indeed, Lum’s exploitation of Blackness for laughs is just one example of several Asians visible in pop culture who have leveraged anti-Blackness to gain a competitive advantage. The predominantly uncritical support that these films and figures have received therefore further exemplifies how Asian representation discourse is so often animated by anti-Blackness.

The fixation on representation and recognition has left many Asian North Americans competing to share the “diversity spotlight” with other racialized communities, forgetting or ignoring that they too continue facing barriers to representation. This is especially true of the Black community, which has been saddled with what many Black thinkers and scholars call the “myth of Black privilege”. Mark Tseng-Putterman contextualizes the myth of Black privilege against Asian hyperfocus on representation politics. In brief, this faulty narrative maintains that what little available representational diversity exists is being “hogged” by Black issues, falsely shifting the blame for underrepresentation toward Black activism and away from white supremacy. Even putting aside the questionable benefits of hypervisibility, the idea that Asians North Americans need to diminish Black representation in order to achieve it for themselves is not just untrue, but harmfully counterproductive to achieving any sort of meaningful racial justice. Instead, it merely sows unwarranted discord and resentment.

The tension and jealousy that the myth of Black privilege creates often rises to the surface in times of Black media success. As Tseng-Putterman points out, the anti-Black hashtag #OscarsSoBlackAndWhite gained visibility after Moonlight became the first film with an all-Black cast to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. That was in 2017, just two years after cultural critic and diversity advocate April Reign first criticized the lack of diversity in Hollywood with the #OscarsSoWhite hashtag. While #OscarsSoWhite does not in any way exclude non-Black people of colour from its demand for more diversity, many Asian North Americans have nevertheless used the occasional recognition of Black people at the Oscars as more evidence that when Hollywood hears “diversity”, all it really hears is “Black”. The #OscarsSoBlackAndWhite hashtag channels this frustration to insist that Black people use their platforms to advocate more for other racialized communities, and that society at large begin taking the grievances of non-Black people of colour more seriously. In response, feminist writer Mikki Kendall has countered with her own hashtag #NotYourMule, which resists the call for Black people – especially Black women – to perform activist labour on behalf of others and encourages non-Black people of colour to take on that labour themselves.

So, it is disappointing that with Parasite giving Asians the spotlight and the mic, they haven’t had much to say about the dearth of Black filmmakers, actors, and other film workers from this year’s list of Oscar nominees – let alone winners. In a year in which Cynthia Erivo was the only non-white acting nominee, Janelle Monae felt it prudent to bring back the “Oscars so white” phrase during her ceremony-opening performance. And, just as in previous years, dissenting Black voices speaking out against anti-Blackness were met with calls of “what about us?” from non-Black people of colour. When Leslie Jones refused to vote for non-Black nominees, she was reprimanded for neglecting Parasite, because “Asians and Latinos are less represented in the media than [B]lack folks even.” This reflects the regrettable pattern of non-Black people of colour demanding solidarity from Black people, and then failing to return the favour.

Ironically, Parasite itself contains valuable insights into solidarity that some Asian North Americans seem to have missed completely. Asian American record label 88rising made an Instagram post that proclaimed, apparently seriously, that Parasite’s Best Picture win was proof that “anyone can make it no matter where you’re from”. Yet as one Twitter user pointed out, the film’s themes make it clear that just the opposite is true: the Kims will never be the Parks, no matter how convincing their charade, nor how violently they clamber over the backs of Moon-gwang and Geun-sae to get there. In doing so, Parasite shows us that fighting each other over ruling class aspirations is ultimately a futile race to the bottom, a lesson that representation-hungry Asian North Americans would be wise to heed.

As we leave Black History Month behind for another year, it is crucial that we continue to remember and honour this legacy, and work to build a future in which strong, reciprocal Afro-Asian alliances support the struggles of working-class, racialized, and otherwise marginalized communities around the world.

Finally, it cannot be ignored that the simultaneous erasure of Black film workers and celebration of Parasite at this year’s Academy Awards took place against the backdrop of Black History Month. The lack of solidarity on the part of Asian North Americans with their Black counterparts during this time does a gross disservice to the debt we owe Black activists for their immense contributions towards equity and justice not only for themselves, but all racialized peoples, including Asian North Americans. As we leave Black History Month behind for another year, it is crucial that we continue to remember and honour this legacy, and work to build a future in which strong, reciprocal Afro-Asian alliances support the struggles of working-class, racialized, and otherwise marginalized communities around the world.

Nicholas Wong is a recent MA graduate with an interest in race, media, and culture. He is a Chinese-diasporic settler currently residing on the traditional territories of many Indigenous peoples, including the Mississaugas of the Credit, the Anishinaabeg, the Haudenosaunee, and the Wendat, in what is widely known as Toronto. You can follow him on Twitter (@laiseeboi).

Learn more about Reappropriate’s guest writing program and submit your work here.