By Guest Contributor: Sean Miura (@seanmiura)

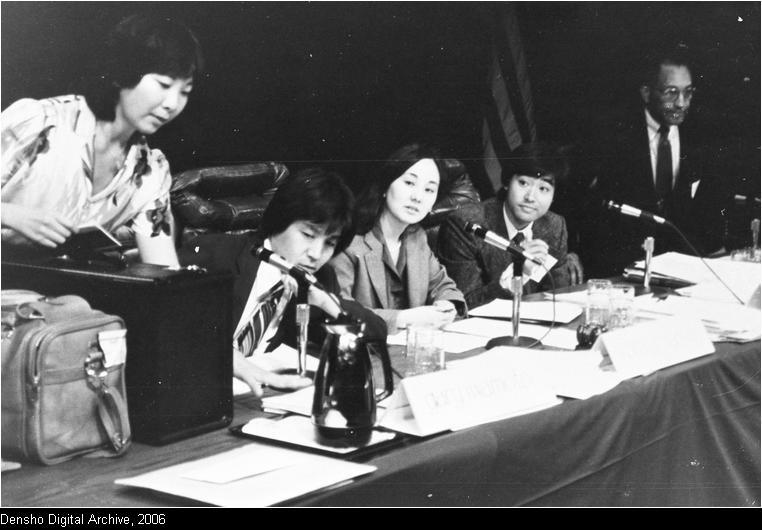

My mom was about my age when she testified in support of Japanese American redress.

Fresh out of law school, she had moved to Seattle a few years prior and quickly found herself pulled into the local Japanese American community as a young leader, eventually becoming president of the Seattle Chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League. Seattle, beautiful rainy Seattle, is a city of left-leaning intellectuals and artists, organized and ready to mobilize with fiery intent and focused action. The Japanese Americans were (and are) no different.

When communities across the country began the push for recognition of wrongdoing in the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans, Seattle became one of the centers of organizing and strategy-setting.

And there was my mom, alongside so many others who fought to make it happen in a layered, complex, beautifully complicated weaving of people who came together to make it happen.

And happen it did.

* * *

In 1942 President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. The Executive Order would lead to the imposition of a curfew on and the incarceration of 120,000 Japanese Americans without due process during World War II.

Decades later the country would find itself in a historic era of civil rights and anti-war activism. Across the country, activists, artists, and educators whose families had been incarcerated would start to call themselves Asian Americans instead of “Oriental.” They would also start to uncover family histories that their parents hadn’t shared. In remembering their incarceration, many parents processed the trauma as shame — this contributed to a community-wide silence. This silence meant that many young Japanese Americans would learn about their parents’ incarceration for the first time during the civil rights movement.

In the late 1970’s a culture of Asian American activism had matured and community organizers began a push for redress — a formal apology and monetary compensation. The national Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) passed a resolution in 1978 which stated that the organization would push for a formal apology and individual payments of $25,000.

Grassroots organizations like the National Coalition for Redress/Reparations (NCRR) formed to gain traction within local communities. Organizers networked across the country and worked closely with politicians. A class action lawsuit was filed by the National Council for Japanese Americans Redress (NCJAR) which applied further pressure.

In 1980 Congress established the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC), which held hearings across the country. In these packed and sometimes deeply emotional hearings, former incarcerees, community leaders, and experts presented testimony on the impact of EO 9066. For many of the former incarcerees, this was the first time they had spoken about their experiences. The silence and shame were beginning to recede.

Three years later, the CWRIC would publish its findings in a report called Personal Justice Denied. The report identified the key factors behind the Executive Order as “…race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership.” This report would also recommend that the government issue an apology, pardon those charged with violating curfew or who were convicted based on race or ethnicity, develop a fund for public education/community development, and issue individual payments to surviving incarcerees. This didn’t guarantee actual action but it was a step in the right direction.

Organizers, activists, and politicians would continue to work on obtaining redress and four years later it would pay off. In 1987 Congressman Norman Mineta introduced a bill titled H.R. 442, a nod to the WWII all-Japanese American 442nd regiment. A year later, on August 10, 1988, President Reagan signed the bill into law, granting an apology and a monetary payment of $20,000 to each living former incarceree.

* * *

My mom doesn’t like to take credit for her work. While I was writing this very piece, she stopped to show me a timeline she had quickly drawn that chronicles her life in the 80’s. The intended effect was for me to see just how few years she was involved in redress, but instead it highlighted the fairly significant length of time she was involved and the remaining years she spent leading a team during the coram nobis cases.

This was a national movement fueled by so many people and so many organizations it’s no wonder that one person would feel uncomfortable taking credit, even in part. The campaign may sound like it was a smooth process with a unified approach but the reality was not so tidy.

During redress, the organizations, politicians, and individual contributors took many different tactics. At times there were different goals and strong disagreements as to what the community should ask for. Many wanted the individual payments that were eventually given but many wanted the community to settle for a community fund. Many Japanese Americans had reservations about the fight for redress overall and didn’t want either an apology or money as neither could give back what had been taken from them.

To me, however, this is why the battle was won. Despite the disagreements and misalignment, ultimately everyone returned to the table to continue the work. The allowance for conflict and reconciliation was a powerful, indispensable tool.

Mistakes were made, public arguments were had, and schisms were formed, but through all that the organizers, whether grassroots or on Capitol Hill, never lost sight of the ultimate goal and the heart of the campaign. As former incarcerees began to pass on, their children wanted nothing more than justice for the deep wrong and they allowed that to drive the work forward.

As a country we will continue to make devastating mistakes and we will refuse to learn from them. This year alone we’ve seen the Muslim travel ban and the inhumane incarceration of families crossing the border, both of which have parallels to 1942 that cannot be ignored. Just as the redress organizers and politicians did, we must and will undoubtedly have to continually hold our government accountable for its actions. We’ll do so by knowing who we are with and what we are up against.

In this era of social media shaming there is so much pressure for organizational perfection and political purity. We must be critical of each other, we must butt heads, and we must take moments to have the hard conversations and pull over if necessary, but we must never lose sight of the road ahead. Ultimately it will take all of us if we are to win any of the fights we engage. To win, we have to always return to the table.

The fight for redress opened an avenue for the Japanese American community to find justice and vindication. An apology can never correct the past or fully right a wrong but it shows that a country, even this country, can course correct and do the right thing. We have to keep ensuring that it does.

Read more:

- Densho – The Redress Movement

- NCRR: The Grassroots Struggle For Japanese American Redress And Reparations

Sean Miura works with Buzzfeed and is also the producer and curator of Tuesday Night Café, the nation’s longest-running Asian American open mic night. He can be found on Twitter at @seanmiura.

Learn more about Reappropriate’s guest contributor program and submit your own writing here.