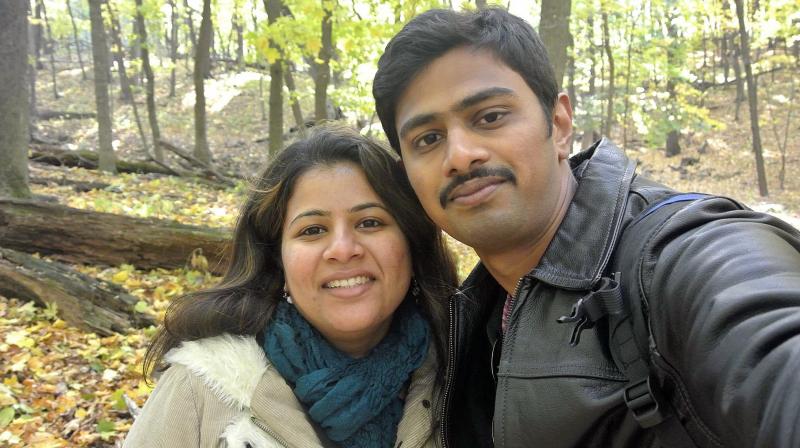

Earlier this year, I reported on the hate crime murder of 32-year-old Srinivas Kuchibhotla, an engineer shot and killed at a bar in Olathe, Kansas by a man who yelled “Get out of my country!” moments before pulling the trigger. The shooting left Kuchibhotla dead and his co-worker — with whom he was enjoying happy hour drinks — critically injured; a third bystander who attempted to stop the crime, was also hurt.

Afterwards, the killer — 51-year-old Adam Purinton — fled the scene of the crime and was later apprehended nearly 70 miles south at an Applebee’s, where Purinton had boasted of killing two Iranians. After he was arrested, Purinton faced federal hate crime charges; he currently awaits trial on those charges.

Heartbreakingly, Purinton didn’t just take the life of Srinivas Kuchibhotla that night in February; the shooting also placed Kuchibhotla’s widow — Sunayana Dumala — at risk of deportation. Dumala, who was born in India, worked as a developer for InTouch Solutions; however, her residency status was linked to her husband’s H-1B visa. When Kuchibhotla was murdered in February, Dumala’s residency permit was terminated and she became at risk of deportation.

The US immigration system is complex and extremely difficult to navigate for even those familiar with the system; immigrants — often challenged by language inaccess and unfamiliarity with the American legal system — often face massive difficulties obtaining or maintaining documented status. Indeed, 66 percent of newly undocumented immigrants in 2014 were visa overstays — immigrants who lost documented status for any number of reasons including through the institutional failures of an unwieldy immigration system. These undocumented immigrants significantly outnumber those who enter the country without documented status.

Those who have never attempted to navigate the US immigration system likely do not know how precarious documented status can be to maintain; and yet, these are the kinds of voices who too often dominate the immigration debate in America.

Being an immigrant in America comes with profound limitations on one’s life. Immigrants find that their residency visas linked to their specific jobs, and they are forced to maintain continual employment at that job for the years — or even decades — it can take to obtain permanent residency and eventual naturalization. If they lose their jobs (such as due to mass layoffs) or if they want to leave their jobs (for reasons that might include a desire to relocate with family, a career change, or even workplace harassment), they risk their visa status and jeopardize any pending residency applications with US immigration. Others — often women — have their residency status linked to their spouses, which ties them to the marriage and prevents them from leaving. This can be life-threatening for immigrant women who face domestic abuse. Such was the case for Nan-Hui Jo, a domestic violence survivor who faced the impossible choice of staying in an abusive relationship with the sponsor of her legal immigration status, or fleeing with her daughter but becoming an undocumented immigrant.

Those who demand that all immigrants “wait in line” to enter the country likely have little real experience with US immigration: the process of documented immigration is neither easy, nor cheap, nor humane. Once, when I was an undergraduate student on a student visa trying to reenter the United States after Christmas break, a customs agent chastised me for not having all my paperwork immediately available and in order. “Being in this country is a privilege, not a right,” he yelled at me, sometime before midnight as I and the other half-awake passengers on my Greyhound bus filed quietly past him to have our passports inspected and our fingerprints digitally recorded. Implicit in his statement was the following: that I was an imposition; that I didn’t have to be here; that I should be grateful for being in the country; that I could be turned away at any time; that I didn’t have any rights worth respecting; that I should shut up and take the verbal abuse he was dishing out to me and my fellow huddled masses and move along before he decided to really exercise his power over us.

Since that experience, I have been very careful to maintain my visa status through over seventeen years of living and working in America. I have maintained the kind of meticulous records that the ordinary citizen might think unnecessarily exhaustive. And yet, lacking proof of minute details — such as the dates, ports of entry, and flight numbers of every international trip I’ve ever taken in my entire life (including as a child); my tax records for the past decade; and every club or organization I’ve ever attended a meeting of — could put my immigration status at risk during inspections. Even with such meticulous records, I have periodically had my status at risk, for reasons as simple as a closed office making me unable to get paperwork signed in time, or my visa being lost in the mail and therefore being invalidated. (Correcting mundane errors like these is possible, but time-consuming and expensive, and even a record that they occurred can jeopardize future applications.)

Ms. Dumala faced the absolute worst-case scenario: the death of an immigrant’s sponsor nullifies an immigrant’s existing residency status and any pending applications.

Dumala’s husband, Srinivas Kuchibhotla, was in the United States on an H-1B visa — a visa class specifically intended for highly-skilled foreign workers that is sponsored by a worker’s employer. The vast majority of H-1B visa holders are Asian, however the program has been temporarily suspended by the Trump administration. Prior to this year, approximately 85,000 H-1B visa applications were issued each year, and visas are only valid so long as the visa holder maintains a job in their specialty. The spouses of H-1B visa holders can apply for an H-4 visa as a dependent of an immigrant on an H-1B visa, which allows them to obtain a drivers’ license and pay taxes and also grants some visa holders work authorization. 90% of H-4 visa holders are women.

Dumala was an H-4 visa holder at the time of her husband’s murder, and the couple had a pending application for permanent residency status (colloquially known as a “green card”). With Kuchibhotla’s death, Dumala’s visa — which was valid only as a dependent spouse of her husband — was revoked, and she was forced to scramble to obtain visa status of her own in order to remain in the country. Her and her husband’s application for a green card — a process that can take nearly a decade for immigrants from China and India due to annual green card caps — was nullified leaving her back at square one. Furthermore, without a valid visa, if Dumala returned to Hyderabad, India — the place of her husband’s birth — to attend his funeral, she would likely be unable to return to the United States at all. Without intervention, it was unlikely Dumala would be able to obtain legal status of her own: the grace period grated to her upon her H-4 visa’s revocation did not permit her sufficient time to apply for an H-1B visa of her own, and she would most likely have been forced to leave or become a visa “overstay”.

This is the reality of how US immigration policy heartlessly treats immigrants every single day.

There is a further irony: under the RAISE Act immigration reform proposal backed by several Republicans and the Trump administration, Dumala would likely not ever have qualified for an immigrant visa on her own. Furthermore, had Dumala’s husband lived, Dumala would still have faced the possible loss of her work authorization under Trump.

Unlike many immigrants, Dumala’s case was taken up by her congressman, Representative Kevin Yoder (R-Kansas). Yoder helped Dumala re-enter the United States after she decided to leave in February to attend her husband’s funeral, and he helped her secure work authorization for a year that would grant her the time to apply for her own H-1B visa. Dumala is also applying for a special U visa, which pertains only to the victims and family members of certain violent crimes who agree to cooperate with law enforcement in the prosecution of that crime.

For now, Dumala no longer faces deportation. However, her status — like that of most immigrants — remains unstable. Dumala’s fate, like that of all immigrants, is at the whim of the labyrinth-like US immigration system — one wrong or unfortunate move is all it takes. Even a sincere desire to comply with all immigration policies does not protect an immigrant from ever finding their status at risk due to errors in filing, the realities of life, or unforeseen tragedies like what happened to Dumala.

It goes without saying that immigrants — both documented and undocumented — benefit the United States and its economy. Immigrants contribute billions of dollars in state and federal taxes, and few qualify for or receive social services. Immigrants are less likely to commit violent crimes than citizens, and most work or attend school in this country.

But, beyond all that, immigrants — both documented and undocumented — are human beings seeking to live the quintessential American Dream: to make a life better than the one they left behind.

Therefore, immigrants deserve sensible, humane comprehensive immigration reform that removes the kind of red tape that makes it difficult — and sometimes nigh-impossible — to maintain documented status. We need to learn about the real, lived experiences of being an immigrant in this country, particularly if we want to have a meaningful conversation about comprehensive immigration reform.

We need to stop treating immigrants like they should just be thankful for the worst treatment that our government can muster. Instead, we must support our immigrant community by overhauling our existing immigration policy, which currently employs a head-spinning system of paperwork supplemented with the threat of state violence and criminalization to make it exceptionally difficult to immigrate. We must replace our current system with new immigrant-centered legislation that finally treats immigrants with the respect and dignity that all people deserve to have.

Being here is a privilege, but that shouldn’t also mean that immigrants should have no expectation of basic rights or humane treatment.