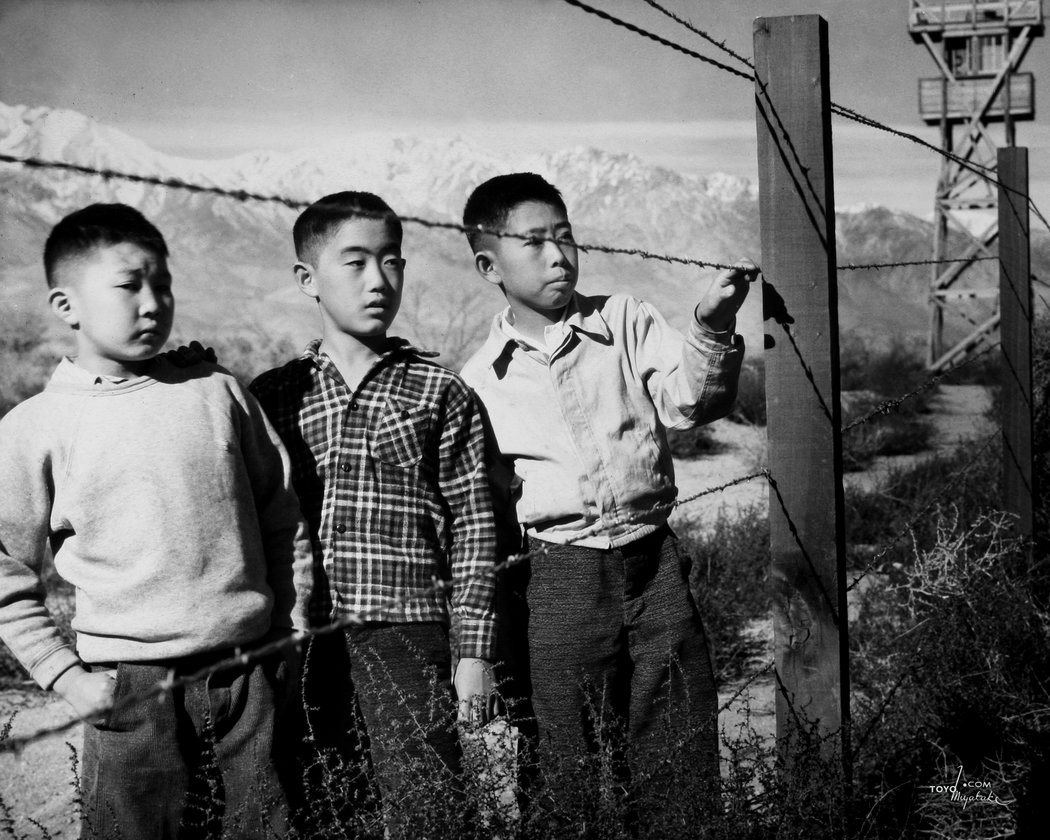

75 years ago today, an American president passed an executive order that led to the forcible removal and incarceration of 120,000 Japanese and Japanese American men, women and children in American concentration camps (Note: JACL’s Power of Words Handbook).

For years, Japanese and Japanese American civilians were imprisoned in hastily-erected assembly centers and camps under harsh, isolated conditions and guarded by American soldiers whose guns were pointed inward. Racism lay at the root of this incarceration: America’s federal government offered the thin reasoning that incarcerees’ race was proof that Japanese American citizens and their parents were spies for the Japanese military. Actor George Takei was a child of 5 when he was labeled a threat to national security by his government, and forced by gunpoint to a distant incarceration camp.

Today, America is poised to repeat the mistakes of its history. A new president sits in the Oval Office who routinely uses the spectre of national security threats to target groups of people with discriminatory executive action. Compared to 1942, the victims may differ but the federal government’s reasoning is the same: entire communities of innocent civilians are being labeled as enemies of the state by virtue of their race alone.

Japanese American history remains highly relevant to today’s political moment, in no small part because it is frequently cited by the Right as such. Last November, Trump supporter Carl Higbie appeared on Fox News’ The Kelly File to reference Japanese American incarceration in defense of Trump’s plan to institute a Muslim registry. When challenged, Higbie insisted that the federal government’s targeting of certain groups based on race or religion — in 1942 or now — was acceptable because, in his estimation, “we need to protect America first.”

To accept the reasoning that Japanese American incarceration serves as affirmative legal and moral justification for the targeting of Muslims today, however, requires that one agree that neither effort by the federal government is racist and unconstitutional. Such an interpretation is not only incorrect, but ahistorical. In 1942, the federal government’s labeling of Japanese Americans as national security threats was racist; in 2017, the federal government’s labeling of brown Muslims as national security threats is, too.

The denial of Japanese American incarceration’s racism is essential to its apologists, who would instead advance the suggestion that America’s mass imprisonment of thousands of civilians was reasonable and justified. Last December, the LA Times published two reader letters that described Japanese American incarceration as justified; the Times‘ editorial board later apologized for that decision. Last month, the Tri-City Herald published a guest editorial by Columbia Basin College Associate Professor Gary Bullert asking, “was the relocation of West Coast Japanese racist?” Bullert answers this rhetorical question with an essay that lays out the underthought reasoning often adopted by Japanese American incarceration’s most ardent defenders. Unsurprisingly, similar talking points are used today to defend executive action against Muslims.

Bullert begins his defense by suggesting that Americans were correct to fear and villainize the Japanese. Citing the “naked aggression” of the Japanese military, Bullert reminds his reader of Pearl Harbor and the mistreatment of American prisoners of war during World War II. (Never mind, of course, that no American was imprisoned in a Japanese war camp when Executive Order 9066 was passed.) Instead, Bullert uses Pearl Harbour as Donald Trump uses 9/11: for both, a terrible assault on American soil is repurposed to portray an entire group of people as national security threats based on the most tenuous and insubstantial of connections — shared race or religion — with America’s attackers. This then serves as cover for illogical and unjustifiable racial profiling.

Bullert fails to distinguish between Japanese Americans and those Japanese nationals who were employed as actors of the Japanese state prior to World War II. In doing so, Bullert models the same racist logic as President Franklin D. Roosevelt when he signed Executive Order 9066, and Donald Trump’s flawed logic today. Bullert cites the example of Takeo Yoshikawa — a Japanese spy who provided intelligence on Pearl Harbour before the 1941 attack — to rationalize the assertion that Japanese Americans should be deemed untrustworthy. Yet, unlike Japanese Americans and their immigrant parents who had chosen to adopt America as their new home, Yoshikawa was a spy specifically placed in America for the purposes of espionage. Yoshikawa was not a part of the Japanese American community; indeed, he disdained Japanese Americans, finding them widely “uncooperative” to his cause. Indeed, no Japanese American has ever been found guilty of facilitating the attack on Pearl Harbor, yet this did not matter when they were being forcibly removed from their homes at gunpoint. Still, Bullert chooses to ignore the clear, if inconvenient, distinction between Japanese Americans and foreign Japanese spies. This same generalizing racism is in play today. Last month, President Trump passed an executive order to ban Muslim immigrants temporarily — and Syrian refugees indefinitely — from entering the country on the grounds that they included “foreign nationals who intend to exploit United States immigration laws for malevolent purposes.” Like Bullert, Trump fails to see beyond race (and religion) to enact a patina of suspicion over all brown Muslisms. Indeed, race — more than national security — seems to be Trump’s primary motivating factor: none of the 9/11 attackers hail from the seven countries whose Muslim immigrants have been banned by Trump.

Bullert argues that Japanese American incarceration was not racist because not all Japanese Americans were incarcerated by the executive order. Similarly, many defenders of Trump’s Muslim ban note that his executive order does not openly state that it targets Muslim immigrants, and further remind us that only Muslims from seven countries are affected. Yet, a law need not explicitly state that it seeks to target a specific group based on race for that law to be discriminatory: in 1886, the Supreme Court ruled in Yick Wo v. Hopkins that a law that is race-neutral in appearance but prejudicial in practice is still unconstitutional. Furthermore, a law is no less problematic if it only manages to successfully disenfranchise some members of that marginalized group. Any initiative by the government to target a group of people based on their identity — whether to incarcerate Japanese Americans or to ban brown Muslim immigrants — is obviously discriminatory. Indeed, the underlying racism in both these efforts is evident in their execution. In the 1940’s, Chinese Americans fearing that they would be mistaken for Japanese Americans and included in the forcible removal order took steps to clarify that they were not Japanese. Today, non-Muslim brown immigrants are being detained and subjected alongside Muslim immigrants for heightened government scrutiny; meanwhile, white immigrants pass through Customs and Border Enforcement checkpoints largely unscathed.

Only after decades of activism by the Japanese American community did the US government offer muted acknowledgement of the crime of Japanese American incarceration. Survivors of American concentration camps received reparations and a government apology, but the American justice system maintains that the mass incarceration of an American civilian population remains legal. Today, we find ourselves still fighting the same battles to educate America about the facts of Japanese American incarceration, and still challenging false (and insulting) defenses of one of America’s great sins against its people.

Asian American history, like the history of many communities of colour, is replete with examples of the American government enacting racially discriminatory laws to marginalize and oppress its minority civilian population. Today, as we remember Japanese American incarceration history, we must also remember how precariously close this country is to enacting this same sort of state violence against other groups. 75 years ago today, American racism labeled Japanese American men, women and children enemies of the state and placed them behind barbed wire fences to keep them away from the rest of American society. Let us not find ourselves 75 years from now commemorating a new Day of Remembrance marking the day when President Donald J. Trump passes new executive action to replicate old patterns of racism against new targets.

Today, it is not enough for us to passively remember Japanese American incarceration. Instead, we must — as a country — take action and join our allies in stopping American history from repeating itself all over again.