So, I’m on a roll this week, posting about why I believe we — as Asian Americans, as Americans, and as moral human beings — have a responsibility to stand up against the growing tide of Islamophobia that has swept this nation and flooded social media with stories of fearful Muslims facing disgusting forms of harassment.

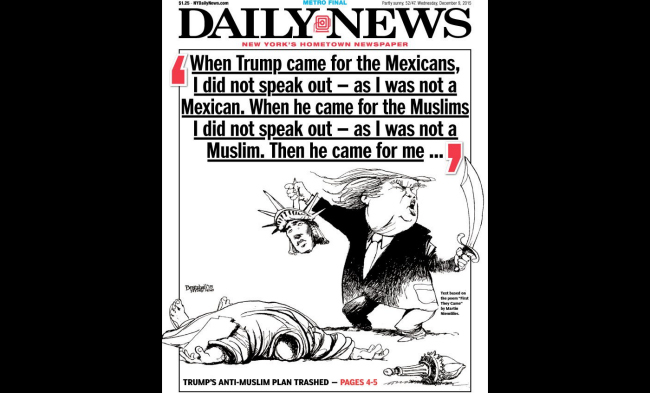

On Monday, I connected this country’s remembrance of Pearl Harbour with the anti-Japanese xenophobia that followed, and urged readers to see the similarities between racist fears of World War II and today’s Islamophobia. On Tuesday, I reacted to GOP front-runner Donald Trump’s announced proposal to ban all Muslim travel with my comparison between Trump and noted turn-of-the-century Sinophobic race-baiter, Denis Kearney. Again, I urged readers to parallel the era’s anti-Chinese hatred with today’s intolerance of our Muslim American neighbours. Both of these post went pretty viral this week, and thanks to you, readers, for that!

Of course, Islamophobia would not be America’s folie du jour without folks rallying to its cry. Earlier this week, a commenter named pzed posted a defense of the proposal that Muslims from some (vaguely specified) parts of the world face greater stringency during immigration because according to this author, they (or their children) would take up the banner of Islamic fundamentalism. When later pressed upon this point of view, pzed wrote:

I said that a significant amount (sic) immigrants (and possibly their kids) from nations that have a significant fundamentalist population aren’t likely to share your progressive views. The Paris shootings were conducted by both homegrown and foreign fighters.

…[A]s the Boston bombing and recent mass shooting in California demonstrate, there are Muslim immigrants from areas with a higher percentage of fundamentalism that are (sic) turn out to hold fundamentalist views here in the US. This shouldn’t be shocking to anyone.

…You keep trying to link Asians to the Syrian cause because of our shared history of discrimination. I certainly agree both Chinese/Japanese were and Syrians are discriminated against. But unfortunately there simply aren’t many historical examples of Asians and Asian Americans terrorizing other Americans.

(I’ve done my best to objectively summarize this commenter’s viewpoints with excerpts that most clearly present their point of view, but of course any digest runs the risk of altering meaning. I invite you to read the full comments here and here.)

It’s a little tough to decipher pzed’s full meaning — particularly with regard to which countries’ immigrants they feel are worthy of extra scrutiny — but this is my interpretation of their basic thesis: this commenter argues that (some) Muslims should be treated with hostility and suspicion because they believe that Muslim refugees (“from areas with a higher percentage of fundamentalism”) are either already secretly fundamentalist terrorists or more predisposed to become fundamentalist terrorists (then, say, Asians?), and therefore Muslims — simply by virtue of existing — pose an immediate risk to the lives of non-Muslim Americans.

I wrote a lengthy response to this commenter that I also posted to Facebook (something I don’t normally do). The response was so overwhelmingly positive with so many folks asking me if they could re-post the comment that I decided to adapt my writing into a post so that it could be more easily shared.

The problem begins with pzed’s writing begins with their cherry-picking of history — arbitrarily focusing on the Boston Marathon mass bombing and the recent San Bernardino shooting — in order to support their hypothesis. This is done without regard for studies of larger trends of domestic terrorism that demonstrate that pzed’s overall assertion is based more on racial stereotyping than it is on fact.

Almost nothing ties the Boston Marathon bombers (Dzokhar and Tamerlan Tsarnaev) to the San Bernardino shooters (Syed Rizwan Farook and Tashfeen Malik) except that both groups of attackers were Muslim. Other than this fact, Syed Farook was a US-born highly-Americanized Pakistani American, while his wife, Tashfeen Malik, was a foreign-born Pakistani raised in Saudi Arabia. Federal investigators believe Farook and Malik placed their loyalty with ISIS. The Tsarnaev brothers were foreign-born Kyrgystan Americans who were raised in Chechnya who were relatively recent immigrants to America, and whose apparent affiliation were al Qaeda. There is no clear racial or ethnic commonality between them. Further, ISIS and al Qaeda are not only not the same thing, but they are in fact declared enemies of one another. Most would be hard-pressed to find any sort of common ethnic or racial pattern between these two examples considering how different the two groups of perpetrators are from one another in almost every sense.

Nonetheless, pzed argues that Muslim immigrants and refugees from (vaguely defined) parts of Central, Western, and Southern Asia pose an unusually high risk for radicalization. Yet, the vast majority of the roughly 500 individuals arrested and prosecuted for jihad-related domestic terrorism since 2001 have been US citizens. The vast majority of those individuals have also been charged primarily with non-violent crimes — mostly delivering material aid to overseas terrorist organizations — not for conspiring to or actually carrying out violent attacks either overseas or domestically. In the cases where domestic plots are uncovered, it seems as if suspects were spurred into planning a violent crime by undercover FBI agents or informants, calling into question the possibility that these suspects were entrapped or even encouraged to radicalize by federal agents seeking to build bigger cases. In that same time frame, no refugees have ever been arrested for planning or enacting acts of domestic terrorism.

It becomes clear from a consideration of these cases altogether that the actual risk posed by radicalized “homegrown” jihadi terrorism carrying out acts of mass violence that cost the lives of other Americans is actually relatively low. Recent events notwithstanding, in general, we are far more likely to die by the actions of domestic terrorists who declare affiliation to White supremacy, or men’s rights, or anti-government groups then by the acts of terrorists who swear allegiance to fundamentalist Islamic terrorist organizations. Perpetrators of domestic terrorist acts are most likely to be White men, yet no one has suggested that we treat with suspicion all White men. Pzed does not urge us to treat incoming German or Norwegian immigrant families with greater scrutiny because they or their children are more likely to be radicalized towards domestic terrorism by neo-Nazi organizations.

Instead, pzed (like many other pundits who engage in Islamophbia) chooses to focus on domestic terrorism involving fundamentalist Islamic ideologies, even though by definition, this filters one’s consideration to a sampling of cases involving Muslim-identifying terrorists in order to build a faulty causative conclusion about Islam and terrorism. One cannot conclude that the Islamic faith predisposes one to terrorism when one chooses only to a priori consider terrorist acts that involved Muslim individuals. Regardless, researchers at George Washington University have highlighted that pzed’s basic argument about the causative relationship between Islam and terrorism is based more on bias and stereotype than on fact. In describing the 71 individuals facing jihadism-related domestic terorrism charges since March 2014, they write:

The profiles of individuals involved in ISIS-related activities in the U.S. differ widely in race, age, social class, education, and family background. Their motivations are equally diverse and defy easy analysis.

These individuals are White, Black, Asian or Latino. They are (predominantly) male, or female. They are foreign-born, or US-born. They run the gamut from fundamentalist Christian in upbringing to Muslim-raised. In the aggregate, there is no clear evidence for the hypothesis that immigrants from war-torn South Asian or Middle Eastern countries (or their children) are more likely to radicalize as jihad-inspired domestic terrorists.

In fact, just under half of the 71 cases of jihadism-related domestic terrorism involve converts to Islam, not people raised as Muslim from childhood. This is higher than the incidence of converted adherents in mainstream Islam, indicating that young people raised in mainstream Muslim families are actually somewhat protected from becoming jihad-inspired extremists compared to those who convert.

Indeed, the vast majority of “homegrown jihadism-inspired terrorists” are young, self-radicalized individuals who become increasingly extremist as they navigate the “echo chamber” of fundamentalist Islam’s social media network. When they are arrested, they typically are charged with sympathizing with overseas terrorist acts; 75% faced no charges related to planning or carrying out their own violent acts.

In fact, a careful analysis of the data suggest that those who become self-radicalized are swayed less by a deep personal belief in fundamentalist jihadism, and more by a desire to find community, belonging and security wherever they can. We can see this superficial relationship to fundamentalist ideology by the fact that most domestic terrorists arrested since 2001 were not affiliated with any specific overseas group (whether ISIS, al Qaeda, Hamas, etc). Instead, their grasp of the language and ideology of fundamentalist jihadism is tenuous at best, and their progressive radicalization arrives through the learning and adoption of the language of their virtual community in order to better assimilate with this in-group. In short, these are alienated kids who become attracted to extremism and terrorism because the social network that recruits them to the ideology fills the social void that comes with being ostracized from the mainstream. I’m summarizing the findings of this study, and encourage you to read more here.

“Homegrown terrorism” is no new phenomenon, but it has found a resurgence through terrorists’ strategic use of the internet to identify and recruit disaffected youth to their cause. The simple fact is that the appeal of these terrorist organizations (whether white supremacist groups, anti-government militias, or jihadist organizations) crosses racial and ethnic lines, and can be attractive to young people of all backgrounds. The commonality is not ethnic or racial background, but a potential recruit’s feeling of alienation and isolation from the mainstream, which is co-opted and replaced with a misguided sense of belonging and purpose to serve a violent extremist ideology. For the recruit, the details of the ideology itself is more interchangeable than their integration into a tight-knit virtual community.

Thus, one could argue that when it comes to growing “homegrown jihadi terrorists”, it is Islamophobia that could be considered the chief radicalizing element. If we want to stop jihad-inspired domestic terrorism, the solution is not to promote intolerance and racism towards Muslim individuals; that only encourages at-risk individuals to find community in fundamentalist Islamic circles online. The more we point the finger at Islam, the more we drive disaffected youth (either raised Muslim or encouraged to convert into it) into the arms of ISIS’ Twitter-based social media world.

Lastly, pzed draws a distinction between Asian refugees and Syrian refugees because, supposedly, no one ever thought Asian refugees posed a military or terrorist threat to the lives of Americans. Yet, at the height of the backlash against Japanese Americans, Pearl Harbour and examples of Japanese American citizens educated overseas in Japan and joining their military efforts were used to villainize America’s Japanese American population. During and after the Korean and Vietnam War, Americans earnestly believed that incoming refugees would mask the entry of enemy combatants trained to kill Americans. In the era of Denis Kearney, racist fears of the impact of Chinese labourers on White unemployment was based on the fact that lost wages was as costly to Americans’ lives then as physical violence is by today’s standards.

Of course, pzed argues that neither in the case of Chinese labourers, nor of Japanese Americans, nor of Southeast Asian Americans was there any evidence of an actual attack carried out on American soil. Well, at the time, people really thought Japanese Americans posed a legitimate physical and military threat to America — heck, Michelle Malkin still thinks that today — even though we now know that the actual threat level posed by these groups was extraordinarily low. In fact, in all thee cases, it was history and hindsight that vindicated the marginalized group.

By the same token, people today really do think that Muslims pose a legitimate physical and military threat to Americans, even though we can demonstrate that here, too, the actual threat level posed by Muslim refugees with regard to domestic terrorism is extremely low.

Pzed accuses me of a reflexive defense of immigration. It would seem to me that the reflexiveness is being committed by those who would instinctively generalize Muslim Americans as more likely to commit terrorism, and who would use this prejudice to legislate suspicion of an entire group of people based on their fears of this faith (and ethnicity) alone. These are bigots who would treat the entire Muslim and Muslim American community with hostility for the acts of a tiny percentage of its most radicalized members, regardless of evidence to disprove this racist stereotyping.

Over the last century, those who whipped up fear over Japanese Americans, Southeast Asian American refugees, and Chinese Americans believed they were justified in their hysteria by the perception that each of these groups posed a unique and dire “threat” to the safetiy and security of America, and that this excused a policy of racist suspicion and profiling. Eventually, these fear-mongers were found to be on the wrong side of history.

Don’t be on the wrong side of history with regard to Muslims, pzed.