While parents across the country took their kids to see Big Hero 6 (#1 in box office sales this weekend at $56.2M) this weekend, an equally numerous number of audiences decided to hit up theatres to check out Interstellar (#2 in box office sales this weekend at $50M). Snoopy and I were one of those childless couples who turned out late Friday evening to my local IMAX screen to catch the last showing of Christopher Nolan’s cosmic epic.

And, wow, was it worth it. While I won’t go so far as to call Interstellar my favourite film in the Nolan catalogue, this was yet another spectacular, breathtaking example of Nolan at his finest. Interstellar is a film that demonstrates a true understanding of science fiction; and in so doing it brought into stark focus the progressive deterioration of science fiction movies over the last several years, and how this has left science fiction buffs like myself starved for a return to the essence of the genre.

Classic Science Fiction as a Political and Philosophical — not Scientific — Genre

As popular as Interstellar has been this weekend, it has also been divisive among self-described geeks and nerds. Aggregate scores for the film are largely positive — it has earned a 74% mean critic score on Rotten Tomatoes and a far-less-meaningful 9.1 on IMDB — yet, the internet abounds with critics and bloggers ripping the film a new one. Chief among the criticisms of the film is its scientific errors: one reviewer at Slate, Phil Plait, has written a lengthy screed pointing out that one of the planets depicted in the film defies known physics, and one of the film’s climactic scenes involving a black hole should result in Matthew McConnaughey’s untimely demise.

As a scientist, I agree with Plait — there are some obvious scientific inaccuracies in Interstellar. But, I disagree with Plait in thinking this sinks the film. Scientific inaccuracies abound in most classic science fiction — if the lightsabers of Star Wars are made of lasers, they are physically impossible; faster-than-light warp speed as depicted in some episodes of Star Trek shouldn’t cause people to evolutionarily devolve, as has been suggested in Voyager; the spice of Dune is biologically improbable. We accept most of these errors without issue because while the mark of good science fiction is one that presents a science that resembles contemporary knowledge, “good” science fiction also freely breaks the rules of known science when such deviation enhances the book or film’s central (non-scientific) themes. Let’s remember: the genre is called science fiction, not science fact; works of science fiction are not intended to be technical manuals.

In fact, science fiction isn’t really a scientific genre at all. Science fiction is a political and philosophical genre.

If you think back to every single enduring science fiction classic, you’ll note that what ties them together is not their use of accurate science, but their larger relevance to the politics or philosophies of their time. 1984 is a commentary on authoritarianism; Star Trek a discussion of globalism; Star Wars a conversation on colonialism. It doesn’t so much matter that the voyage depicted in Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth is clearly scientifically flawed; what matters is the story’s relevance to the debate over creation, evolution and the origins of man that was contemporary to the story’s writing. It’s not really relevant how the hermaphrodites of Ursula LeGuin’s Left Hand of Darkness came to be; what matters is how the story uses the androgyny of her characters to explore existential concepts of love and death. It doesn’t matter how the Machine in Metropolis actually works, what matters is the film’s social metaphor.

Science fiction isn’t even really told in plot; it’s told in set design. Great science fiction establishes itself in the first chapter, in the universe built by the author, and in the conceits of this fictional microcosm. Great science fiction occurs when the skilled writer creates a plausible universe simultaneously exotic and alien, while still politically and philosophically relevant to our world and our society. Great science fiction uses fantasy to comment about reality. The scientific accuracy isn’t intended to be the star, it’s only a tool used to add credibility to the created universe.

In my mind, science fiction that depicts scientific inaccuracies thoughtlessly and without context — Gravity‘s choice to have Sandra Bullock cry tears that fall down her cheek while she is in the vacuum of space in a scene that would be equally as compelling with the tears behaving as they scientifically should — is an example of science fiction done wrong. But I also think that nitpicking a science fiction film’s scientific inaccuracies when the errors are clearly committed deliberately to advance the film’s overall themes is, I think, missing the point of science fiction. The Matrix Trilogy’s blurring of the division between the online and offline world in the extent of Neo’s powers frustrated many fans, but those criticisms ignored the Wachowski siblings’ purpose: to transcend Neo into a Christ-like figure. That Neo’s powers stopped making sense on an obvious scientific level was actually the point. Even though the viability (let alone the fertility) of alien-human hybrids are biologically improbable (and, maybe downright impossible), we tolerate Spock in Star Trek because his existence augments the larger story Star Trek is trying to tell about interracial harmony.

So, Plait is right: Interstellar has some science problems. But, to focus on those errors is, I think, to miss seeing the forest for the trees.

What ‘Interstellar’ Is Really About

Ostensibly, Interstellar is about a guy who goes into space to save a dying Earth, and the adventures he encounters therein. But too many of the negative reviews I’ve read of Interstellar have focused on the play-by-play plot mechanics of the film (which, to be fair, is how too many reviews are written these days) and those reviews miss what is truly spectacular about the film: how it, like so much classic science fiction of a now bygone era, employs a near-future science fiction story to tell a meaningful and relevant (and partisan) political story about today’s America. The details of what happens to Matt McConnaughey and his band of space explorers is less relevant than the universe that McConnaughey inhabits. What astounds in Interstellar is Nolan’s concept, and his message.

From the opening scenes of the film, Nolan parallels a near-future dystopia with the early twentieth century Dust Bowl years suffered by much of Middle America. This is a stroke of pure genius: the Dust Bowl of the 1930’s was a period of extended drought caused by man’s overfarming and destruction of a lush grassland, rendering the land toxic and dead. It is an indisputable example of mankind’s capacity to both change and demolish the environment, and also offers a clear demonstration of the consequences of man’s failure to address our self-destructive behaviour.

The invocation of the Dust Bowl is compelling: Nolan opens his film with interviews suggestive of those conducted with survivors of the 1930’s and the first half of the film is set in an all-wooden rural American farmhouse, but he then interrupts that setting with the casual interspersing of more contemporary technology — a laptop, a model of the lunar lander — to signal that his story actually takes place in a near-future Midwest. The dissonant effect is evocative and relatable: immediately, we understand that Interstellar is about conservative America and the climate change debate. Nolan, in essence, creates a 170-minute epic that demands an answer to the enduring question: “what’s the matter with Kansas?”

The universe of Interstellar is the conservative dream taken to its nightmarish next step. The American government has imploded, urban America has self-destructed thanks to food riots, and all that remains are the rural townships of the Right’s romanticized “Real America”. But, again evoking the consequences of a twenty-first century conservative American ideology run amok, drones mindlessly patrol the skies now lacking any sort of human oversight, and a teacher’s luddite denial of the moon landing invokes the anti-evolution debate of today. America is starving, and has fallen to anarchy. NASA operates in secret after the now-defunct US government was forced many years ago to abandon space exploration publicly due to lack of popular support for scientific off-world efforts. This is a world that Reaganites might unwittingly cheer on, and that’s precisely Nolan’s point; this isn’t any kind of America anyone wants to live in.

In this universe, the world is dying — we imagine although we are never told for certain that this is due to man-induced climate change. Regardless, throughout the film, Nolan’s juxtaposition of Dust Bowl imagery with space exploration synergize to argue both Middle America’s central role in driving the climate change debate — for better or for worse — as well as its apathy to this problem. Nolan proposes that it is Middle America, as both the land’s food-growers and also as those who politically oppose environmentally sustainable efforts, who are both empowered to address climate change and who doom us all in their refusal to do so. Nolan suggest that conservative America’s failure to think beyond their own self-interest might be both the more acutely humane, and yet ultimately the more self-destructive position.

Nolan instead challenges conservative America to repurpose compassionate conservativism: McConnaughey’s character of Cooper rejects the manipulative social engineering of other characters (who might reasonably represent a perversion of the Left) and instead leverages his own emotional selfishness to find a way to save all of humanity. Some criticize Nolan’s slow pacing in Interstellar; I assert that Nolan paces the film this way to further underscore that saving the planet by reversing climate change will not be exciting or romantic, it will be a slow, gritty and unrelenting scientific slog. Others suggest that Nolan’s political message is ham-fisted: yet, if that is the case, why do so few reviews seem to address it?

In Interstellar, Christopher Nolan demonstrates a fundamental understanding of the science fiction genre in his creation of a futuristic dystopia to tell a world about our current political climate. In a world where the United Nations just published their latest report suggesting climate change is rapidly becoming irreversible, and yet rural America just elected another slate of climate change denialists in the 2014 Midterms, the message of Interstellar is as timely as it is necessary.

Diversity in “Interstellar”

Given this central theme of Interstellar, it has surprised me that some have criticized the film for its depiction of a non-diverse American future. Some have even panned Interstellar for what they claim is yet another White Savior Complex film, and have dismissed the film for its lack of non-White heroic protagonists. Stuff Black People Don’t Like writes:

Every image that accompanies this trailer is of white people: struggling to survive, to live; fighting to grow and sustain for the next generation; understanding the limitations of the imagination is a recipe for destitution and failure.

It looks like a trailer directly from the studios of the Third Reich, propaganda for a people resolute in their greatness and resolved to move forward.

Simply put, it’s a glorification of white people.

It’s true that the world of Interstellar is racially homogenous; but, considering the film’s point regarding the self-destructive nature of rural America (as detailed above), that is precisely the point. Interstellar is talking predominantly to (White) Middle America, but through watching the film, it is clearly not a superficial glorification of White people. Instead, it is telling the American Right that their persistent self-interest (re: their obstinant denial of climate change) is going to kill us all, and that their embrace of a more “selfless selfishness” is both possible and necessary to stop our otherwise inevitable destruction. Most of the characters in the film represent some romanticized aspect of conservative America whose self-interest is both emotionally resonant and damning: from the rural farmer who clings so desperately to his farm that he ignores the life-threatening ailment of his child, to the chiseled square-jawed astronaut marooned alone on a planet and the choices he makes as a result. In a high-concept film that serves as an unabashed political gauntlet thrown down to conservative Middle America, criticism of the film for its lack of non-White protagonists seems to fundamentally miss the point. (Incidentally, this is also why you don’t review a movie based on its trailer.)

Don’t get me twisted: I believe in diversifying science fiction. What I don’t agree with is establishing a hard-and-fast diversity rule. To want science fiction as a genre to more courageously tackle subject matter that includes stories about me is not to require that all science fiction must include me. For a genre that is about politics and philosophy, such a hard-and-fast rule sets a stifling creative limit on the kinds of stories that this genre can tell. We should instead hold science fiction to a standard that judges how it uses diversity — or doesn’t — to thoughtfully build a fictional universe that enhances its central message; in this genre, context must be key.

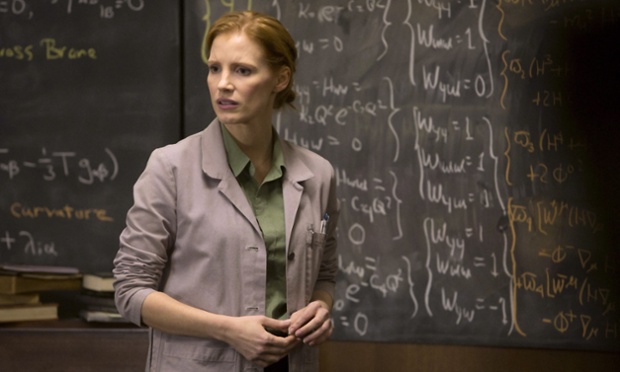

In the details, I further don’t really get the charges that Interstellar failed to depict heroic non-White male protagonists. The film is overtly feminist, depicting two of the best examples of intelligent and compelling women scientists that I’ve seen in science fiction film; further, I wouldn’t be surprised if its portrayal of a young Murphy Cooper inspires a number of young female moviegoers to pursue a career in STEM. In addition, a Black male scientist is portrayed as the most intelligent of the spacefarers. This characterization actively rejects the stereotype of the brawny Black muscle, and — without giving away any spoilers — his role in the final outcome of the film is as essential as McConnaughey’s.

But, more to the point, I share Neil deGrasse Tyson’s opinion that Interstellar uniquely diversifies the portrayal of scientists and engineers in film. Unlike in most other science fiction, where the scientist is either unscrupulous or inept, the scientists in this film are the heroes. Moreover, like with Star Trek, Interstellar‘s production team doesn’t shy away from moments where it took creative license with its science; instead it piques interest in the underlying scientific concepts it breaks, while encouraging its audience to learn more about science.

In #Interstellar: All leading characters, including McConaughey, Hathaway, Chastain, & Caine play a scientist or engineer.

— Neil deGrasse Tyson (@neiltyson) November 10, 2014

In #Interstellar, if you didn’t understand the physics, try Kip Thorne’s highly readable Bbook “The Science of Interstellar"

— Neil deGrasse Tyson (@neiltyson) November 10, 2014

So, while I agree that Interstellar isn’t the most racially diverse film you’ll see in the realm of science fiction, it’s also more progressive than some critics are giving it credit for.

Summary

Interstellar encapsulates the essence of what science fiction is as a genre: a fictional universe designed specifically to communicate and emphasize some sort of political or philosophical message about society today. In Nolan’s pointed use of Middle American imagery to talk to rural America’s conservative voters about the politics of climate change, I can envision no better example of what science fiction as a genre is capable of.

Sure, this was a movie about black holes and tesseracts and adorable anthropomorphic robots. But, it’s also a compelling, engaging conversation about carbon emissions and the Keystone pipeline, and the very real impact of conservative America’s science denialism on climate change; all gift-wrapped for us in the beautiful visuals of IMAX special effects.

We would do well to watch this film — and more importantly, to — as a country — listen and think.