Thousands of protesters took to the streets of Hong Kong this week to participate in a mass act of non-violent civil disobedience against the Chinese government. For days, protesters — many of them college-aged students and teenagers — have gathered near the city’s government buildings; they are chanting, marching, raising their fists, sleeping on the street, and wielding umbrellas against tear gas — all in defiance of a political and economic ruling class that threatens to revoke a democratic process promised to Hong Kong voters since the city’s 1997 handover from British rule to the Chinese government.

Most of us have been enthralled with the events in Hong Kong right now. We are following the events in Hong Kong with anticipation through mainstream news and social media. But, we must do more than offer just our support for the events taking place on the streets of Hong Kong right now; we should be getting inspired. Hong Kong’s Occupy Central protests are not just another demonstration happening somewhere halfway around the world; they have become an international symbol of freedom against political and economic tyranny that is informed by, and is informing, the experiences of AAPI and Americans alike.

Those of us in the West should be taking note.

How anti-Asian Stereotypes Shape Our Reaction to the Chinese Democracy Movement

Historically, agitation against Chinese power has centered around the independence movements of disputed regions — including Taiwan and Tibet — who assert their autonomy from a nation they argue has only oppressed their interests and their people. For the West, this narrative is also predicated upon the the illusion of a monolithic Chinese political behemoth that finds support throughout all aspects of Chinese society. Rarely do we in the West appreciate that the political opinions of the Chinese layperson can be as varied and diverse as any we might see elsewhere in the world. The West routinely fails to appreciate the complex spectrum of Chinese politics; that failure is reinforced by our internalized dehumanization of non-White people and culture.

Americans characterize their own voters as deeply committed to representative democracy and who prize free speech above all else. We celebrate our history of social movements, and characterize our citizens as opinionated and educated. Edward Said’s Orientalism teaches us that against this landscape, the only space that “the Orient” can occupy is the “anti-West”. It should come as no surprise, therefore that the vision of Asian politics in the West is reminiscent of our contemporary perspective of the Asian American: the average Chinese voters is the submissive, apolitical “model minority” whose stoicism emphasizes American outspokenness. We reserve the ideal of the invested and passionate voter for the West, and deny a vibrant political discourse to the East. Instead, the popular image of the Chinese is (like the Chinese American) one of the tenacious modern-day coolie: hard-working, but politically dispassionate.

For this reason at least in part, America and the rest of the West seems to have reacted with a mixture of surprise and skepticism as the events in Hong Kong unfold; it seems we are having difficulty reconciling our own Orientalist stereotypes of the meek Asian politic with a real-time counter-example of passion and love. Are we surprised, then, that at least a few stories have been written focusing on how “well-behaved” and “clean” the Occupy Central protesters are in their civil disobedience? Even in the coverage of Occupy Central, the Asian plays the role of the “model minority”.

In that context, for Hong Kong protesters to speak out as loudly and as compellingly as they are right now is not just an act of defiance against the power of Chinese government authority, but also an act of defiance against the anti-Asian stereotypes that oppress all of us within the Asian diaspora regardless of the land we stand upon.

The Right to Self-Determination for Hong Kong (and Ferguson)

A revolution cannot, by definition, be “well-behaved”. The use of coded “model minority” words to describe Occupy Central fundamentally diminishes the radicalness of the act, while it castigates protesters in Ferguson who are behaving in similar manner as protesters in Hong Kong, yet have been routinely described as “violent” “looters”.

In Ferguson, protesters are marching against a local government that has repeatedly failed to represent Black constituents politically, and a police force that threatens Black lives physically. In Hong Kong, protesters are demanding that China maintain its commitment that Hong Kong will have a democratic process for electing its leadership. In both instances, protesters represent communities of people without access to political agency.

Black voters in Ferguson and around the country are routinely marginalized by such tactics as gerrymandering and widespread voter disenfranchisement; rarely are the interests of Black constituents prioritized on the campaign trail or as matters of public policy by the leaders of either political party. And although Hong Kong’s government as a British territory was in part democratically elected in the latter years of British rule (clarification: in the form of advisory councils, although executive branch was appointed by British government without democratic input), the history of Hong Kong is that of a land that was ceded first to the British (in the context of a war started when the British hoped to spread opium addiction through China in order to correct a trade imbalance) and then later returned to China against Hong Kong’s wishes. In the grand scheme of things, Hong Kong has spent the better part of the last two centuries as the collateral damage of imperial colonialism.

To that end, neither group of people — whether Black Americans living in the United States or Hong Kong voters living under Chinese rule — has fully realized their right to political self-determination.

The struggle of both Hong Kong protesters and Ferguson protesters should resonate with all of us because in both instances, the causes are righteous. In both instances, everyday people — mostly young people — are rising up against institutions of privilege that advantage an economic and political elite.

This is the central cause of the Asian American Movement, too, as well as for most progressive Americans. Thus, we should not just be watching what’s happening simultaneously on opposite sides of the world; we should be taking part.

The Power of Youth Protest

What I also find compelling about the Occupy Central protests and the Ferguson protests is not just the shared themes, but also the awe-inspiring demonstration of power both have accomplished through coordinated mass protest action.

In America, college-aged twenty-somethings are notoriously (even stereotypically) difficult to turn out to the polls. Asian Americans, too, struggle with some of the lowest rates of voter turnout in this country. Yet, in Hong Kong, a revolution is taking place in the streets right now on a scale that contemporary America rarely has had the opportunity to witness; and it is a revolution organized and powered almost entirely by the city’s young people. All week, these protesters have endured police violence, heavy rain, and clouds of tear gas to take a peaceful stand against political and economic tyranny.

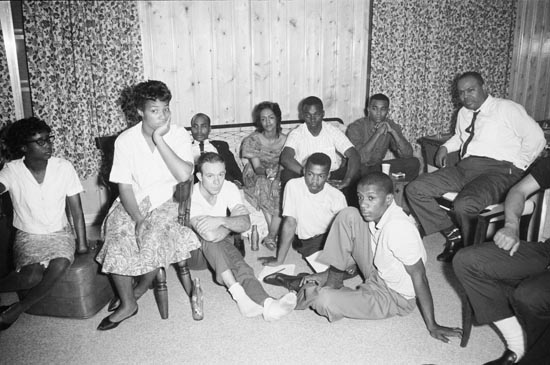

Throughout history, it has always been young people at the forefront of our most influential social movements: the Freedom Riders; the No-No Boys; the anti-Vietnam War protesters; the Occupiers; the Chinese American protesters of police brutality in the 1970’s; the students who defied Governor George Wallace following the passage of Brown v. Board of Education in the 1960’s. Even in China, the face of the democracy movement has always been that of college-aged students: young people whose vision of China is an empowered one, and one worth defying authority (often with profound consequences) to realize.

The lesson here is simple: the masses have power. The power of the ballot box is, of course, critical; but, too often, we are lulled into forgetting the potency of coordinated peaceful action.

We remain far from an equal world. It is easy for us — particularly as we accumulate privilege — to succumb to cynicism and skepticism. Yet, the dual protests in Hong Kong and Ferguson remind us: that revolution is possible; that the cause of social justice transcends international and racial boundaries, and touches something within all of us; that there is strength in solidarity; and that Asians — whether in Hong Kong or here in America — shouldn’t be satisfied with the role of the well-behaved “model minority” bystanders in that fight.

Asians have never embodied the role of the meek and stoic wallflower in political activism; we should not be satisfied with that role today. Instead, we must perpetually reject the comfortable stereotype of the political “model minority”. We must be inspired by the events in Hong Kong and Ferguson this past summer to speak up, to speak out, and to go against the grain whenever we are faced with injustice in our own lives. We must not shirk from radical nonviolent action in defense of a just cause.

And above all, we must cultivate the political activism of our young people; history suggests that in the fight for social justice in America, it will be our AAPI youth who will be — and should be — leading the way towards a more progressive future.

Note: Many thanks to X.Y. for pointing out the need to clarify the degree to which democratic elections were not available to Hong Kong citizens under British rule.