This is a story that deserves far more mainstream attention than it has received.

On May 20, an Arizona State University professor, Ersula Ore, was walking along a road in the direction of traffic when she was confronted by campus police. She was detained and asked to show ID; during the stop, she repeatedly requested that the police officer speak to her in a more respectful tone. We know this because the entire incident — including what transpires next — was captured on police dash-cam.

Although Professore Ore is heard only questioning the officer’s attitude, the police officer eventually throws Professor Ore onto the hood of his police car in order to arrest her. When Professor Ore protests being put in this position while standing next to a busy road — specifically, she is heard citing the length of her skirt — the police officer became violent. He brutally swings Professor Ore around by her arm. She lets out a series of bloodcurdling screams. She lands on the ground off-camera and was arrested.

This is a clear example of police brutality, one with distinctly racial overtones.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eh2lIgBfJZ4

Professor Ore’s case is typical in one sense: an African American woman is detained while doing something completely routine, and subjected to excessive force at the hands of police.

Although she may have been jaywalking (Ore claims she was in the road because pedestrian sidewalks were blocked by a construction site), jaywalking is a minor traffic infraction that rarely results in a stop, let alone a citation or an arrest. Yet, over and over again, it is exactly these kinds of routine stops that lead to extreme police brutality, and — too often for young Black and Brown men and women like Oscar Grant and Amandou Diallo — to death.

It should come as no surprise that the vast majority of police brutality cases in this country involve African Americans and Latinos. Throughout the country, Black and Latinos are between two and three times more likely to be stopped in routine traffic stops compared to Whites or Asian Americans. The vast majority of New York City’s Stop and Frisk stops target minorities — particularly Black men — yet less than 2% result in a conviction and jail time; instead, Stop and Frisk laws and other similar policies of (implied or explicit) racial profiling enable a law enforcement culture built around the widespread harassment of Black and Latino American citizens. This disproportionate attention reinforces stereotypes of Black and Latino criminality, and also enables the kind of routine interactions with law enforcement that can quickly escalate into excessive force and brutality.

Yet, on the other hand, Professor Ore’s beating at the hands of Officer Stewart Ferrin is atypical because — unlike most American citizens — Ore appears to have known her rights.

Throughout the incident, Ore complies with Ferrin’s orders except to stand her ground in requesting that Ferrin speak to her with greater respect; she was well within her rights to do so. Ore identifies herself as an ASU professor; he ignores this. Ore does not immediately hand over her identification; she was well within her rights not to — citizens are not required to surrender identification to police officers unless they are being formally detained, and for most of the incident it was not clear that Ore was being officially detained for a crime (or even that she was actually refusing to give her ID). She does not physically resist the officer at any point until she is already handcuffed. Despite all of these facts, Ferrin chooses to use force far in excess of what is required to handcuff her, throwing her to the ground after she already appears to be restrained. And while Ore did kick Ferrin in the shin at the end of the tape, this is only after she has already been brutally and unnecessarily assaulted.

Earlier last month, ASU sided with Officer Stewart Ferrin, claiming that he conducted himself appropriately. Today, mainstream news is reporting that Ferrin has been put on leave pending an investigation.

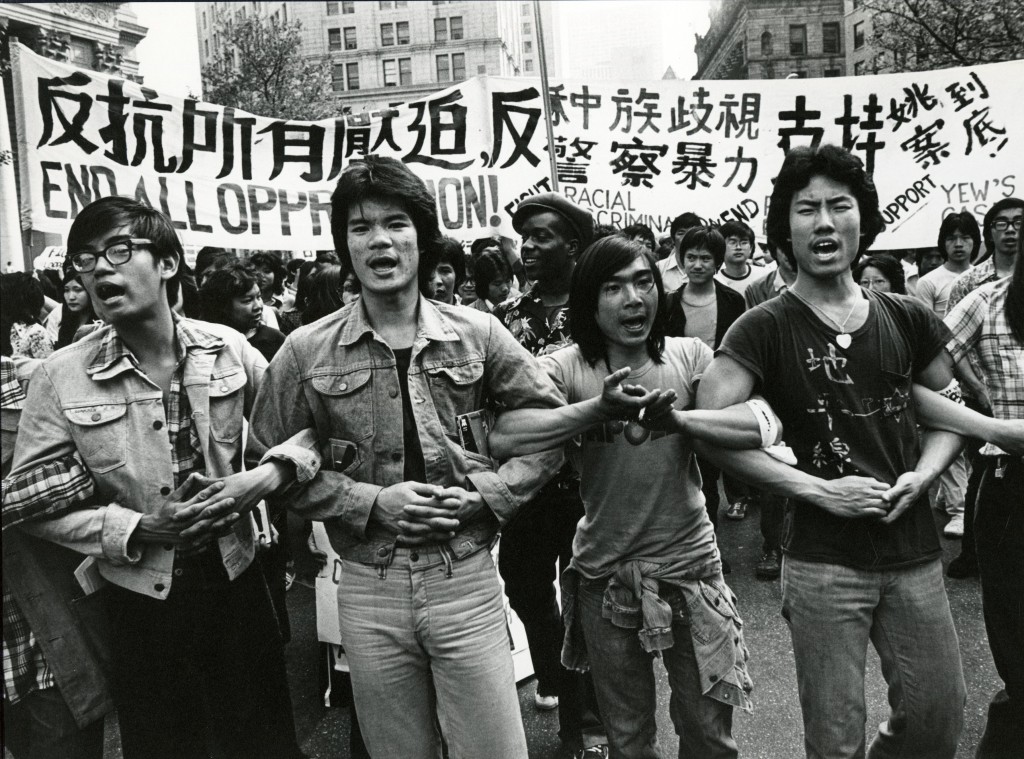

Police brutality is an issue that affects all communities of colour, including Asian Americans. Although in aggregate, Asian Americans appear to be racially profiled and detained at far less frequency than Black and Latino individuals, this is in fact only a recent phenomenon. In the 1970’s, Asian American youths were also racially profiled in urban areas like New York City and San Francisco where we were stereotyped as hoodlums and thugs. Multiple cases of stop-and-frisk incidents targeting young Asian American men escalated into police brutality, and resulted in a series of massive protests and other forms of political resistance.

Today, the modern Model Minority Myth has somewhat blunted the rates at which we experience unjust force at the hands of law enforcement. And although in aggregate we have traded the devastating and dehumanizing impacts of one kind of stereotype for another, individual cases of police brutality still happen to Asian Americans.

And when they do, they often target Asian Americans who are already socioeconomically at-risk due to economic, linguistic or immigration status. When they do, the force is just as devastating. When they do, they are often ignored by that same Model Minority Myth, erasing our very real and very painful lived experiences with institutional racism and oppression.

In 1995, 16-year-old Yong Xin Huang was shot in the back of the head and killed by Brooklyn police officers. Last year, an 84 year old Chinese American man was beaten bloody by the NYPD for jaywalking at a Manhattan intersection. This year, a salon owner was beaten in her place of business by Chicago police while they also yelled racist slurs. In 2009, Vietnamese American teenager Phuong Ho was horribly beaten and tasered by San Jose police while he was on the ground, unarmed, and submissive (very graphic cell phone video below).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qyistav_cjY#t=98

The history is clear: police brutality is an issue that affects all communities of colour, largely without regard to the specific races of victims. And while today, Asian Americans are not being targeted by law enforcement at anything close to the rates experienced by other minority groups, we are not immune to its effects. There is zero justification for standing idly by while some among us are forced to endure this kind of illegitimate and unjustified force at the hands of law enforcement.

We as Asian Americans can ill afford to be silent on this issue, even if the victims of today’s police brutality cases don’t always share our race. Instead, we have a moral responsibility to speak out against police brutality whenever it happens. What happened to Professor Ersula Ore is unconscionable; that it continues to happen too often for too many people of colour — including us — should be unbearable.

We passionately protested on this issue in the 1970’s. We need to recapture that same degree of fervor to protest on this issue today. Because this matters, and it matters for all of us.