(H/T Jeff Yang (@originalspin))

Less than a month ago, Elliot Rodger stabbed to death his three Asian American housemates and then went on a shooting spree in the residential college town of Isla Vista, randomly targeting women and their boyfriends as alleged punishment for society’s emasculation of him. I wrote about how Rodger’s actions were symptomatic of society’s larger definition of masculinity; I coined the term “misogylinity” to describe hegemonic masculinity’s toxic and misguided assertion that men should pursue and covet a masculinity defined relative to the sexual commodification of women. I further discussed how issues of masculinity are of particular interest to the Asian American community, where the racial pain arising from stereotypes of emasculation is explicitly political, and which has rationalized the pursuit — often uncritically, and sometimes outright problematically — of misogylinistic notions of manhood.

I concluded that while misogyny, masculinity and misogylinity is America’s problem at-large, it is Asian America’s problem, too. In some corners of Asian America, radical misogyny incubates virtually unchecked.

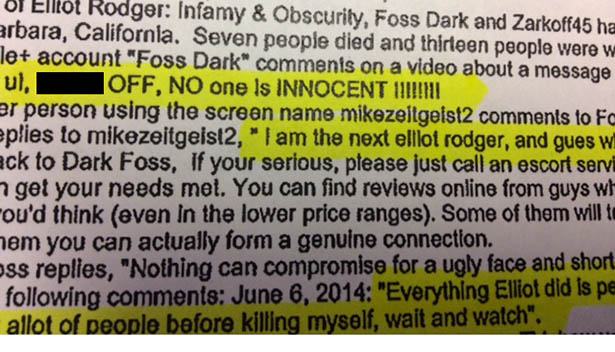

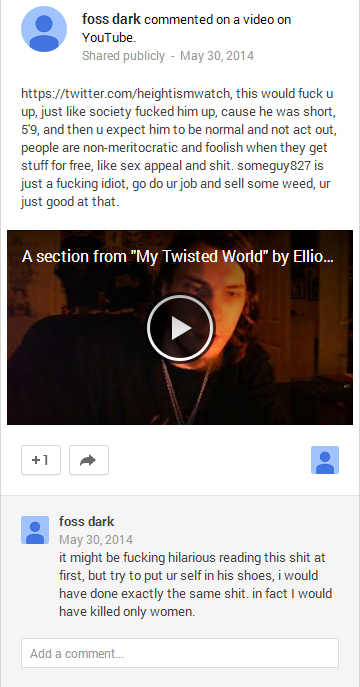

Yesterday, a 23-year-old South Asian American man by the name of Keshav Mukund Bhide was arrested and held on $150,001 bail after posting numerous online comments idolizing Isla Vista shooter Elliot Rodger through YouTube and Google+, the latter through his account name “Foss Dark”. Bhide is a student at the University of Washington.

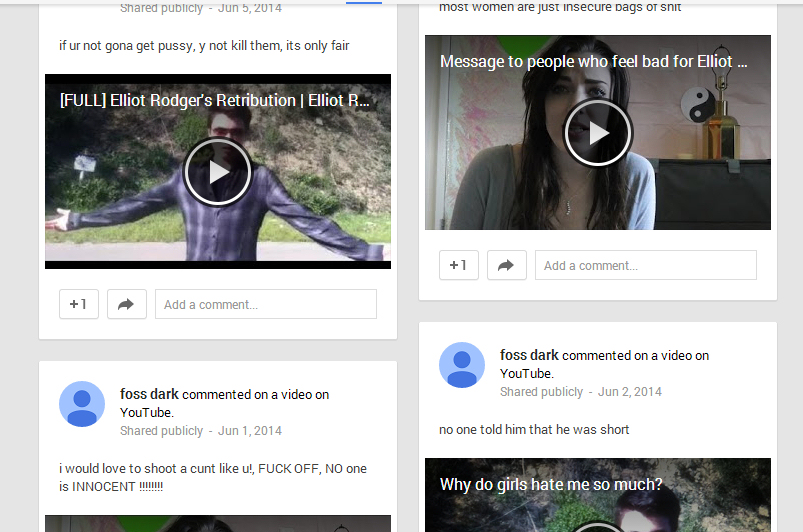

Bhide posted several comments calling Rodger’s “Day of Retribution” “perfectly justified”, and threatening to follow in Rodger’s footsteps. On May 30, Bhide wrote a comment on his own sharing of a YouTube video, saying that he “would have done exactly the same shit” but that he “would have killed only women”.

In explanation for his misogyny, Bhide cited a trope that again is all-too-familiar within the Asian American community: he rationalized his anger against women for society’s rejection of men who are “short” and who have an “ugly face”.

In his Google+ posts, Bhide repeatedly rants against society’s “heightism”, focusing on his perception that short men are denied sex appeal; this is a logic that is frequently used among Asian American men to articulate society’s sexual rejection of them. In a later comment he rationalizes Elliot Rodger’s homicidal spree killing as an expression of his short stature. In still another comment, Bhide says:

Nothing can compromise for a ugly face and short stature, i will execute the same thing. I have no option

Notably, the phrase “ugly face” was used by Elliot Rodger as code for his anti-Asian self-hatred. Rodger, who described himself as Eurasian, believed himself to be “beautiful” for his ability to pass as White. In his 140 page manifesto, Rodger denigrated his Asian American housemates — whom he would later stab to death — for their “ugly faces”, and tried to distance himself from aesthetic signifiers of his own Asian American-ness. Bhide’s invocation of this same term can only be interpreted as a deliberate reference to Rodger’s writing — particularly in the context of his overall praise of Rodger — except that Bhide believes himself to possess the “ugly face” that Rodger rejected.

Like Elliot Rodger, Keshav Bhide believed society owed him masculine and sexual success; unlike Elliot Rodger, Keshav Bhide likely blamed his height and his Asian-ness for his failure.

According to his Google+ account, Bhide — like Elliot Rodger — transferred that anger onto women. He posted videos of women (some of them feminists) discussing societal misogyny and rape culture in the wake of the Isla Vista shooting, and used misogynistic slurs to describe the women. He then expressed a desire to shoot and kill these women.

On June 9th, Bhide posted a comment to an online forum threatening to engage in a mass killing like Elliot Rodger. Claiming to be “the next Elliot Rodger”, he wrote:

‘I live in seattle and go to the UW, that’s all I’ll give you. I’ll make sure I kill only women, and many more than what Elliot accomplished [sic],’ he said.

Concerned onlookers notified the FBI, who tracked Bhide down by his IP address to an apartment building near the University of Washington campus. Bhide was arrested Saturday afternoon and charged with cyberstalking and felony harassment. It is possible that Bhide committed real-life threats against women at UW: on-campus sororities have reported in recent weeks disturbing anonymous phone calls by a man “looking for someone to shoot”, and one sorority found chalk outlines outside their house earlier this month. It is unclear right now whether Bhide is responsible for those acts.

Let me be clear: I do not think misogyny is a characteristic trait of all or most Asian American men. I do not think that our community is alone guilty of the kind of homicidal misogyny expressed by Bhide and his idol, Elliot Rodger.

But it is also counter-factual, and increasingly irresponsible, for our community to ignore the demonstrable fact that this kind of misogyny also finds expression among Asian Americans, where it is shielded in part by larger political narratives over the real and viable pain Asian American men feel over emasculation stereotypes. It is increasingly immoral to sweep our community’s identification with misogyny and rape culture under the rug, because we are afraid that it will make our community look bad, or that this will somehow in turn further deprivilege Asian American men. We should be able to prioritize work that would end stereotypes that target and marginalize Asian American men, and find a way to do so without protecting misogynistic and patriarchal attitudes from within.

As I expressed in this podcast, I think we can all agree that institutional stereotypes of emasculation and asexualization can have real and damaging impacts on the psyche of Asian American men, and that those stereotypes must be proactively addressed and challenged. Yet, our community lacks a larger conversation about the strategies that we use in challenging emasculation, and how our current framing of this political issue might also reinforce radical misogyny at the fringes; this is the conversation we need to be having. We need to be talking about how all of us — Asian American men and women — may be complicit in reinforcing patriarchy, either through our explicit embrace of hegemonic masculinity and misogylinity, or implicitly through our silence regarding the same.

So long as we continue to assert that the lens through which we should both discuss and correct anti-Asian male stereotypes involves dating disparities and outmarriage, we continue to reinforce the notion that women are the gatekeepers that can unlock a masculine revolution for the Asian American man. This, in turn, reinforces the rage expressed by some Asian American men, like Bhide, at women for, in their estimation, refusing to unlock their figurative “gates”.

Keshav Bhide, I am not the gatekeeper for your masculinity; and, I do not deserve to be shot as retribution for society’s racist stereotyping of you.

Last month, I ended my post with a plea I feel compelled to reaffirm today: can’t we be doing better than all this? Can’t we find a better, more progressive masculinity? Can’t we finally take steps to reject a hegemonic masculinity that imprisons our Asian American brothers in the implicit assumption of asexuality, and that challenges them to redeem their own Asian American-ness through racial self-rejection and misogylinity? Can’t we finally take steps to reject an institutional patriarchy that would mistakenly cast women as privileged gatekeepers, which only justifies violence against our bodies when we wield that privilege “wrongly”?

Can’t we do something to prevent any more Elliot Rodgers from thinking they have the right to exact revenge against women for their own racial and gendered pain?

Can’t we finally do something — something — to end this vicious cycle of misogyny and hate?