Leave it to CNN to report on ideas that have been circulating in the blogosphere for years like it’s news, and to further treat those ideas with the kind of insipid, uncritical patina that suggests that the article is the end-result of maybe two hours — tops — of online reading. Leave it to CNN to give a complex and nuanced conversation a Monday morning rush job on an otherwise “slow” news day.

This morning, CNN published an article by John Blake, who normally writes for CNN’s Belief Blog; today Blake was writing about diversity in speculative fiction.

The basic premise of his op-ed? Televised speculative fiction is awesome right now because there are people of colour doing things next to White people.

If [Martin Luther] King clicked on TV today, he might shout that we’ve reached the Promised Land. A racial revolution is quietly taking place on the small screen, and zombies, witches and headless horsemen are leading the way. There’s been an explosion of multiracial casting on science-fiction, fantasy and horror shows, and the people powering this trend say it is here to stay.

Popular shows such as “The Walking Dead,” “Sleepy Hollow” and “Arrow” are giving us a sneak preview of a post-racial America that can still seem far away, fans and creators say. The most eye-popping elements are not the special effects and supernatural creatures but the multiracial casts and the casual acceptance of racial differences. These shows routinely feature actors of color in nonstereotypical roles, and interracial relationships are the norm.

Yes, according to Blake, we have arrived at King’s Promised Land: we have built a post-racial world, and it has zombies in it.

But have we really?

Blake cites the usual suspects in building his argument — Sleepy Hollow, The Walking Dead, and Arrow — and celebrates that actors of colour are populating these worlds alongside White protagonists. And, compared to Kung Fu which notoriously refused to cast Asian American Bruce Lee in the starring role in favour of White-as-the-driven-snow David Carradine in yellowface, Hollywood’s newfound willingness (fifty years in the making) to hire actors of colour is certainly a step forward.

But, the speculative fiction world of TV is still a far cry from King’s Promised Land. Just based on the numbers alone, White actors still make up at least two-thirds of the cast of each of these shows, whereas all minority actors are — regardless of race — thrown together in that last third to contribute to a seething mass of token Brown-ness all in the name of racial progressivism.

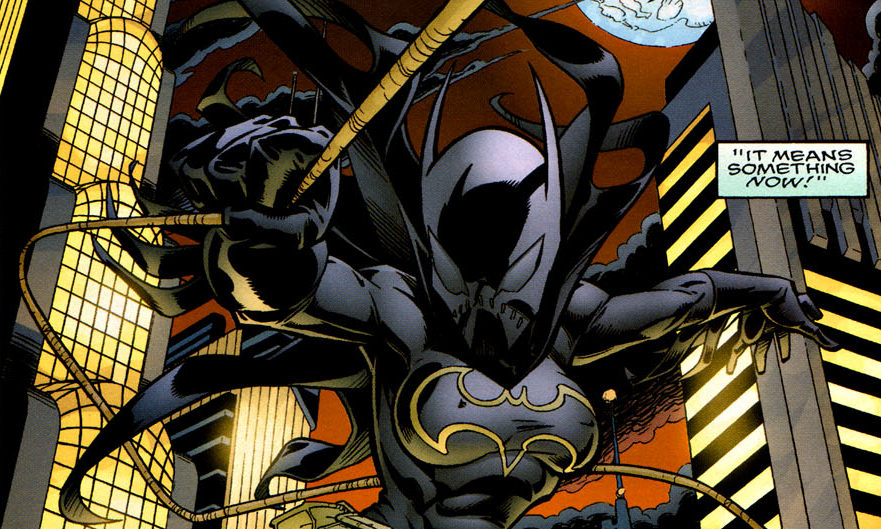

Blake goes on to argue that the purpose of injecting diversity into comics is to create a post-racial world where people of colour exist alongside White people in being superheroes.

That’s just not enough.

It has been five decades since Bruce Lee was excluded from the cast of Kung Fu; why is speculative fiction still focused on the tiny goal of normalizing people of colour? For today’s youth, even those living in all-White enclaves, the fact that minorities exist is about as inescapable as one’s Twitter timeline. That we are capable of amazing feats is no more obvious than when a minority peer kicks your ass in the classroom, and then does it again on a football field. If a kid grows up in today’s world thinking minority kids are by virtue of our race incapable of achievement, then they won’t learn that lesson from science fiction.

The base inclusion of people of colour in speculative fiction shouldn’t be celebrated, it should be expected. We should demand more than this.

Argues Blake:

Lee’s inability to get the lead role in the TV series that became known as “Kung Fu” is a well-known story. There’s been a long debate over the specifics of his involvement with “Kung Fu.” Still, the only consistent role Lee could get in Hollywood during the late 1960s was playing the chauffeur Kato in a short-lived series called “The Green Hornet.”

To see how much television has changed, one should look at an engrossing, contemporary fantasy show that bears many similarities to “The Green Hornet.”

The show is called “Arrow,” and while there are Asian actors, none plays a chauffeur. Like the Green Hornet, the lead character of the CW Network show is a wealthy young man who becomes a masked vigilante at night to battle crime. He also has a chauffeur who acts as his bodyguard and confidant. The hero even wears a green mask.

But that’s where the similarities end. The cast of “Arrow” looks like a miniature United Nations: Asian actors play complex characters and love interests; the show’s villain is played by a Latino actor; black and biracial characters are common; and two interracial relationships are central to the show.

The forced parallel between Arrow and Green Hornet aside (“They both wear green”? Really?), there is one pretty stark trend that remains in both shows — people of colour are still playing supporting and secondary roles next to White, straight, male protagonists.

In the intervening half a century of time — which has seen the Civil Rights Movement, as well as passage of the Voting Rights Act and the 1965 Immigration Act — Tyreese standing stoically shoulder-to-shoulder next to Rick Grimes in The Walking Dead is still people of colour playing the chauffeur, just without the car.

Last season, I wrote about The Walking Dead‘s long-standing “Black Man Problem”. While Lawrence Gilliard Jr.’s Bob Stookey’s superhuman ability to stay alive alongside TWD’s resident Black man, Chad Coleman’s Tyreese, is certainly earth-shattering, The Walking Dead‘s inclusion of two Black men and two Black women is no less stereotypical and secondary to the emotional evolution of the White protagonists today than it was two seasons ago. The budding romance between Stookey and Sasha are still scenery to Maggie’s desperate attempts to reunite with her husband, Glenn. Michonne is still weirdly oscillating between roles as a sociopathic Angry Black Woman stereotype, and Carl’s new Mammy. Tyreese is still walking two-and-a-half steps behind Carol.

Blake discounts these problems to assert that as people of colour, we should be content with our mere presence in the room — that the most superficial, and slap-dash of integration is all that’s needed to create the Promised Land of King’s dreams.

And so we are expected to celebrate the race-bent cross-casting of Michael B. Jordan as The Human Torch, forgetting that — even as the good Reverend understood — the road to the Promised Land is not so easily navigated.

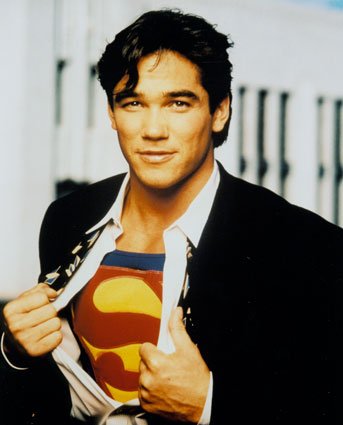

I wrote earlier this year about the problems of racial cross-casting in the pursuit of diversity in comics. Michael B. Jordan’s casting as The Human Torch is not, itself, sufficient to render diversity on the big screen; indeed, in very few cases has racial cross-casting of “race-neutral” roles yielded an outcome that speaks to the racial narrative of people of colour. Idris Elba’s Heimdall is inconsequentially Black in a post-racial Asgard. Biracial Dean Cain’s turn as Superman in the Lois & Clark television show is a prime example of racial passing. The talented Ming Na’s recent decision to assume the role of Agent Melinda May on Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. has resulted in the latest, grievous example of a dragon lady stereotype to grace the small screen.

At its best, racial cross-casting creates inconsequentially diverse characters, because it fails to challenge the post-racial (and often simultaneously racist) framework of the worlds these characters inhabit. At its worst, racial cross-casting creates fundamentally problematic stereotypes when viewed from the distinctly racialized reality of the television viewer. Either way, the racial cross-casting movement asserts the minimally invasive solution of the appearance of race, while ignoring the injection of the far more unsettling realities of race and racism.

I agree with Blake that speculative fiction, and its televised counterparts, has long positioned itself at the forefront of literature in driving social progress forward, and doing so through a medium of literature. But, if Dune had the power to explore Whiteness through futuristic imagination, should not today’s science fiction explore minority-ness with the same nuance and complexity? If, as Blake argues, speculative fiction is intended to be a mirror that reflects society’s racial diversity in order to teach youth about race, than we must ask ourselves what lessons we are teaching when the reflection is filtered through the rose-coloured glasses of a post-racial fantasy. Is there a more meaningful lesson to be learned from Uhura’s tacit rejection of the pain of her own racial distinctiveness, or from Captain Ben Sisko’s embrace of it? If science fiction should reflect the racial realities of our world, should it not reflect it in all its beauty and its flaws?

Skin colour diversity is by definition meaningless in a post-racial framework, and the televised post-racial world of Blake’s imagining is only real so long as the TV set is on. Rather than to support injections of the appearance, but not the substance, of race, we should be focused on a paradigm shift: popularizing a new wave of speculative fiction that embraces the explicit presence of race — in all its glory and its pain — not the brazen denial of it.

As with many fans of science fiction, Blake argues that injecting the substance of race into speculative fiction is akin to turning the genre into an after-school special: it is boring, a buzzkill, a drag. How often have I and others who assert the injection of race and racism into the pages of comic books been accused of over-thinking the problem; of being “bad fans”?

This criticism is predicated upon the assumption that all discussions of race and racism must have all the gravitas of a slave epic; that because race is uncomfortable, it has no business in a genre that is, at its core, fun. Blake sets up a false dichotomy between science fiction writing and what he pejoratively terms “Roots”-style narratives of racial anguish.

Yet, there are hundreds, if not thousands, of independent minority writers who navigate these dual purposes with success, arriving at unique and forthright characters of colour that serve as protagonists, not supporting characters; that satisfy the visceral thrills of science fiction; and that paint in detailed strokes a racial and culturally authentic portrait of the minority experience. Dwayne McDuffie created the Milestone Universe to tell the stories of superheroes of colour in a distinctly racialized world. Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese still provides the quintessential distillation of the Asian American experience in comic book pages, and is accomplished by marrying second-generation experiences of a Chinese American protagonist with the mythology of the Monkey King.

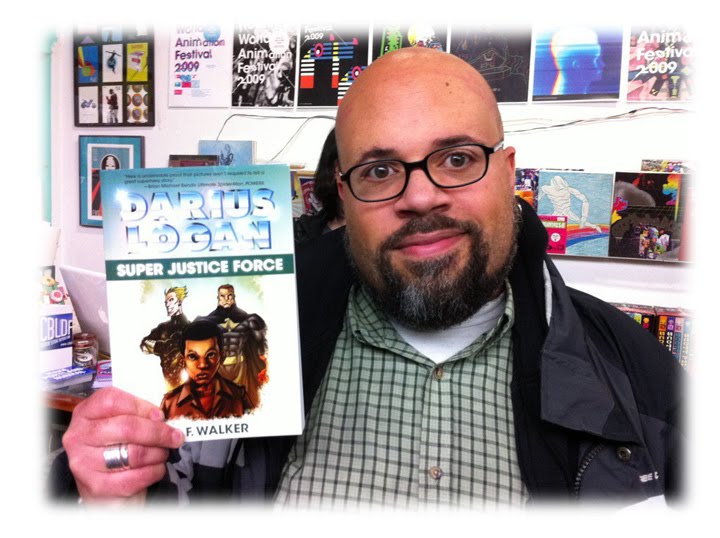

And, recently, I was turned onto the work of David Walker, who in his young adult novel Super Justice Force explores America’s mass incarceration state through the lens of a young Black American man who befriends a superhero society.

In all cases, the exploration of race and racial identity is facilitated by the thoughtful creation of new characters of colour, and necessitates a non-post-racial world.

In the end, I agree with Blake that a diverse world of speculative fiction is a desired end-point. But I fundamentally disagree that the world of science fiction’s imagining should be post-racial. Racial integration of the highest ranks of comic books and science fiction does not require the quick and largely meaningless racial cross-casting of beloved superheroes like Heimdall and The Human Torch; it can be readily achieved through the popularization of new or existing, meaningfully racialized, characters of colour living in a new world that reflects not just the appearance of race, but race itself.

We should not be content to merely be in the world, but to be telling our stories, too.

And that is a revolution that deserves to be televised.

For more: A bunch of blerds I love talked about this, too.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c8QkrJb1uxg