With the growing usage of Twitter as a platform for social justice discussion and organization, a persistent question has been whether and how to combat casual racism in 140 characters or less. The success of hashtags like #NotYourAsianSidekick suggest that Twitter is a powerful tool for bringing together like-minded Millennial activists, yet Twitter is also a hotbed of racism, misogyny and bigotry that can, at times, derail those same constructive conversations.

Over the weekend, two examples of casual anti-Asian racism had “Asian Twitter” in an uproar: a racist Facebook persona awash with yellowface stereotypes created by a local NYC artist, and a Twitter storm of racism and misogyny targeting University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign Chancellor Phyllis Wise.

Both examples of casual racism used Twitter and Facebook as a platform for their racism, and both were the targets of overwhelming Twitter-based backlash. These back-to-back incidents beg the question: does Twitter promote, or merely amplify, casual racism, and how effective a tool is it in combating that same racism?

#FuckPhyllis

Late last night, Phyllis Wise, Asian American chancellor of University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign issued a mass email to the UIUC student body noting that they would not receive a snow day today despite sub-zero temperatures. Disappointed and upset at not having a free day off, students took to Twitter to start the #FuckPhyllis hash-tag, which quickly turned ugly and steeped with racist and misogynistic hatespeech (most of the Tweets have been removed, so I can’t embed them here; Buzzfeed has aggregated some of them despite their deletion).

https://twitter.com/goombatoomba/status/427697624037064704

Buzzfeed also reports that a fake account purporting to be Chancellor Wise was created to tweet racist messages, and quickly obtained over a thousand followers.

The tenor of these attacks are familiar to women, and particularly women of colour, who spend much of our time on the Internet: the instinct to focus on Ms. Wise’s gender and racial identity is an oft-used tactic to silence women of colour through cyberbullying. I have suggested that the Internet’s tolerance of attacks like these may be one reason why women are greatly outnumbered by men in blogging circles.

But what I really want to draw attention to in this post is whether the Internet has become — through the popularity of platforms like Twitter — more tolerant of this kind of hatespeech?

Does Twitter Celebrate The Taboo?

When blogging first became a thing, bloggers like myself celebrated the growing democratization of thought through greater access to minority ideas associated with self-publication. We enthused over how even marginalized identities could create, publish, and promote their experiences through a blog post, and praised a medium that would allow this blog post to potentially reach thousands of readers, circumventing conventional media.

Twitter is conventional blogging on speed.

Twitter, through its 140 character limit, encourages the abbreviation of ideas through the abbreviation of language — often resulting in complex thoughts being thrust into the format of pedantic, stilted, declarative statements that lack the ability (or even the requirement) to be supplemented with supporting context or argumentation. I’ve always felt this format compromised complex discussions of race and identity, and urged hash-tags like #NotYourAsianSidekick to consider supplementing their discussion with blog-based long-form writing; a suggestion that the hash-tag’s founders appear to be pursuing.

But, more relevant to this discussion, Twitter promotes declarative statements while it simultaneously rewards the witty and the provocative. Innately, Twitter (as well as most platforms for blogging or micro-blogging) attracts people who seek a certain amount of attention or readership; these are, after all, mediums for amplifying voice. In Twitter, posting highly-shared tweets leads, inevitably, to greater reach and greater readership in the form of greater follower number; and, anyone who uses these sorts of mediums keeps careful track of our follower number as an “objective” measure of our Internet popularity and ergo success. So, we are all motivated to construct that much-desired thing: a tweet that goes viral.

The virality of a tweet depends on other users favouriting and retweeting it; the objective “success” of a tweet is based on the number of interactions it receives. To achieve these interactions, tweets must compete in a Twitter marketplace where literally hundreds or thousands of other users may be expressing a similar sentiment using the same 140 character-limited space.

Thus, inherent to the system is a competition to “out-wit”, “out-snark”, and “out-provoke” other Tweeters in order to generate the most memorable, most sharable, most outrageous, and thus most viral Tweet.

Not surprisingly, perhaps, that racist and misogynist tweets receive more attention than those that are less outrageous, less provocative, and less inflammatory. Not only do these tweets get re-tweeted by those who revel in expression (by proxy) of otherwise stigmatized hate, but a racist tweet will also be targeted for counter-attack by those who are righteously outraged by the intolerance. Yet, both sorts of interactions are, just that: interactions. More importantly, interactions that serve to elevate a tweet’s virality and promote the tweet’s author.

In short, if the currency of Twitter is attention, one way to generate a high-“earning” tweet in the Twitter marketplace is to construct the racist and sexist taboo tweet. In other words, Twitter actually rewards intolerant tweets, at least in the short-term.

Does Twitter Also Publicize “In-Group” Behaviour?

Admit it: we all say things in private that we would never say in public, whether it’s condemning the co-worker we despise to our significant other when we would never say it in the workplace, or being brutally honest with friends in ways we might never be to acquaintances.

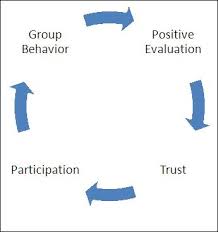

Yet, Twitter and Facebook are places that perpetuate a pretense of an in-group safe space, while obscuring the fact that everything we publish is — inherently — accessible to the entire world.

Thus, in parallel with the fact that outrageous and provocative tweets garner more attention, Twitter and other forms of social networking also foster the fallacy that tweets will only reach one’s friends lists; a fallacy that actually runs counter-intuitive to the very pursuit of virality. Thus, the less savvy, casual user of these platforms is lulled by the general anonymity and controlled network boundaries into treating their Twitter and Facebook like it is a private chat room, and behaving in ways they might never behave were they fully conscious of how harshly public the medium is.

This fallacy comes from the fact that virality is, itself, an abstract notion that depends upon networks linked through immediate as well as removed interactions. Our brains have trouble remembering that your friends have friends you don’t know, and that when you share a thing, you have just shared it with them — and their friends — too. Basically, our brains have trouble thinking past the immediate act of sharing to one’s own list of followers, and we consequently forget that when we publish things to our friends (often in hopes that they will reward us with a “like” or a “retweet”), that when they do so, that post will be shared to an inner circle that is wider than our own.

Arexis Fongman

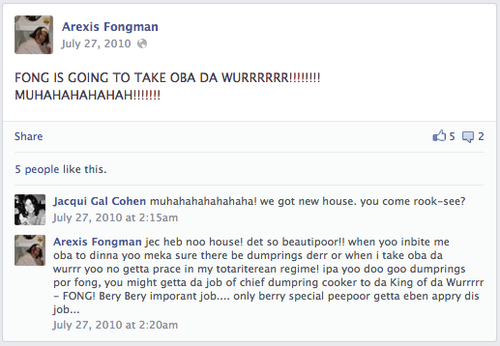

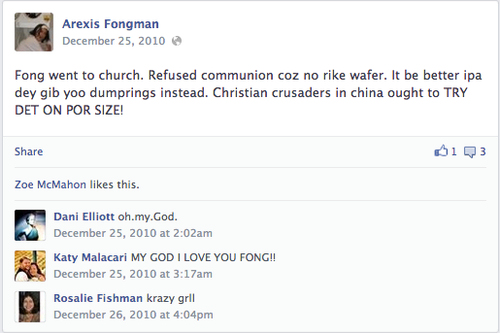

Over the weekend, Asian American bloggers were notified of a fake Facebook account created by a local NYC woman and aspiring artist. Generasian has a full write-up, but in brief, this woman created an alternate persona in yellowface, Arexis Fongman, and posted to this alternate persona’s Facebook and Twitter account in highly racist and stereotypical pidgin.

Arexis Fongman’s persona was not widely shared, but received several interactions from the woman’s immediate friends and family, and seemed to have been built entirely to entertain the artist’s inner circle of friends; in other words, to generate a controlled amount of attention. Indeed, the comments to the Arexis Fongman character by other members of this network — all of which perpetuated the pidgin speech and racist caricatures — suggest that this sort of anti-Asian humour was tolerated and reinforced within the artist’s inner circle.

Yet, the Arexis Fongman accounts were discovered when the artist was introduced (both in real life and later through Facebook) to a person with connections to the Asian American blogosphere; this person subsequently posted about it on his feed where it was brought to the attention by bloggers in his friend list. In short, through only one degree of separation, Arexis Fongman made its way to the Asian Americans blogosphere; yet it’s almost certain that the artist who created Arexis Fongman never anticipated having her accounts be seen by people she hadn’t personally shared it with.

Quickly, the Asian American blogosphere organized a response. Not only did Generasian document the entire racist caricature through their post, but the NYC artist received several tweets documenting the Asian American blogosphere’s outrage. Subsequent to this “Twitter storm”, the artist immediately took down the pages and issued an apology through her own Twitter account, expressing apparently sincere regret for creating the accounts.

More interesting however was the artist’s apparent surprise that this private public thing created as a seriously misguided joke to entertain friends and family was actually very much public.

Can Twitter Be Used as a Tool To Combat Casual Racism?

In this post, I’ve hopefully laid out the argument that racist, sexist and otherwise derogatory behaviour is highly prevalent in the Twitter age through a combination of a medium that rewards provocative and outrageous tweets and the persistent illusion that social networks are private and thus tolerant for “in-group” behaviour. However, the important take-home message here is that Twitter doesn’t create racism and sexism out of whole cloth; it magnifies and encourages latent behaviour that is fueled by internalized attitudes. A tweeter who tweets a misogynistic and racist anti-Asian tweet against Phyllis Wise hasn’t invented that bigotry for the tweet; the tweet draws upon intolerant attitudes within the user and encourages the expression of those thoughts.

We would be kidding ourselves if we didn’t think this kind of intolerance is both institutionalized and widespread, thus we would also be kidding ourselves if we were to be surprised to find that this intolerance routinely finds a voice through the Internet.

So, to some degree, I have come to wonder if these incidents of casually expressed racism and sexism are innate to life on the Internet. Certainly, anti-Asian racism and sexism like #FuckPhyllis, Arexis Fongman, the racist law ad, or the Asian Girlz music video seem to pop up every couple of weeks or so. To borrow a phrase expressed by John McWhorter on Melissa Harris-Perry over the weekend when he was talking about the backlash against Richard Sherman: perhaps this is just a manifestation of the “background evil” of the Internet?

Now, none of this means I think this kind of behaviour doesn’t deserve to be called out. In fact, I am grateful that the Asian American blogosphere so rapidly and so widely spoke out against #FuckPhyllis, Arexis Fongman and other examples provided above. And, indeed, the aftermath of the Arexis Fongman incident indicates the power of Twitter and blogging-based counter-racist attention: less than 24 hours after the Arexis Fongman persona was brought to the attention of the Asian American blogosphere, it was taken down. Similarly, the fake Phyllis Wise account was taken down, the Asian Girlz music video was removed, and the racist law ad maker issued an apology for the ad — all in response to Internet-based backlash.

But, are these kinds of responses sufficient to combat a culture of intolerance? If Twitter is a medium that innately tolerates and encourages racism and sexism-based Twitter cyberbullying, are individual Twitter-based counter-campaigns — even ones that might succeed on a case-by-case basis — also successfully shifting the cultural paradigm away from the root causes of this sort of behaviour?

While Twitter-based counter-campaigns are effective because they overwhelm an offending person through a deluge of anti-racist tweets — a veritable tsunami of shaming — they are also temporary and depend upon persistent action to sustain the “Twitter storm”, placing both the responsibility and the work on anti-racist minorities to fight against behaviour that offenders should really “know better” than to commit in the first place. Further, it’s unclear whether the target of the counter-campaign responds because they have “learned something” or simply because they want to temporarily escape the negative Twitter wrath. To wit, while the creator of Arexis Fongman appears to have actually internalized the problem with her racist caricature, the highly offensive Asian Girlz music video (which was the target of a massive blogging and Twitter-based campaign against video creator Day Above Ground) was removed — but it’s back online now, capitalizing on the fact that the Asian American blogosphere’s (and “Asian Twitter”‘s) attention has turned elsewhere.

So clearly Twitter is a powerful tool for whipping up attention and directing it at offensive material to efficiently dismantle it and extract an apology from its creators; in fact, its efficacy is virtually undeniable at this point. But are these sorts of campaigns sustainable?

And, the lasting question: can Twitter-based anti-racist campaigns actually dismantle the hate-promoting culture and framework of Twitter itself, or the internalized bigotry that this framework draws upon? And if so, how?