This post originally appeared at The Nerds of Color

The critics have been salivating over Alfonso Cuaron’s latest effort, the ambitious science fiction thriller Gravity. And don’t get it twisted: Gravity is pretty darned good. It’s visually and narratively haunting – one of the few contemporary movies that succeeds in marrying a high-concept story with the audience’s (admittedly low-brow) yearning to see things blow up. Also, Gravity is one of the year’s few films that fully takes advantage of 3D technology to establish the various environments that the characters encounter (although I confess I chose to watch Gravity in standard projection because 3D makes my head hurt).

So yes, Gravity is pretty darned good.

But, I just can’t shake the feeling that it could have been so much better.

Spoiler Alert! Please don’t read on if you don’t want Gravity spoiled for you.

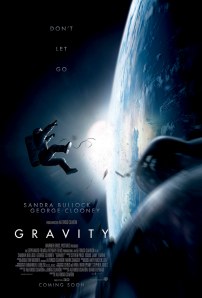

Gravity has all the ingredients to be a spectacular movie. The film’s only cast are two well-known actors playing the comfortingly familiar characters that originally made them famous: Sandra Bullock is the beautiful and panicky civilian bus driver biomedical engineer Dr. Ryan Stone who rediscovers herself amidst exploding objects, and George Clooney is the smooth-talking, cocky and flirtatious emergency room doctor veteran astronaut Matt Kowalski who guides her. And in this, Gravity is somewhat revolutionary: it is truly the hero’s journey of the female Dr. Ryan Stone that takes centre-stage, while Clooney’s Kowalski is indisputably a supporting character.

In Gravity, Cuaron doesn’t set out to merely tell you your standard science fiction space opera, with space ships, laser guns, pointy-eared aliens and things that go boom. Instead (like with his earlier film, Children of Men) Cuaron deliberately chooses the genre of science fiction as a vehicle for exploring contemporary psychological and sociopolitical issues. And, I appreciate this – this is science fiction at its intellectual purest. Science fiction that makes you think.

First, Cuaron references the artificiality of international borders and the futility of isolationism in an increasingly globalized political landscape: the Russian destruction of an aging satellite results in a worldwide chain reaction that demolishes the world’s entire telecommunications network irrespective of national boundary. Later, as Kowalski and Stone are marooned in orbit around Earth, they must seek refuge in the International Space Station and later a Chinese space station – in both cases, they invade international territory and commandeer the property of a foreign government without a moment’s thought to the potential political consequences. The argument by Gravity is that national borders are meaningless in a fast-approaching future where more and more life-or-death situations are of global impact — a perspective that contemporary international relations has yet to even remotely address.

Against this geopolitical backdrop, Cuaron paints a psychological story: he draws a parallel between the vacuum of space and the emotional purgatory suffered by Bullock’s Dr. Ryan Stone. Although Clooney’s Kowalski is quick with a tall tale, it is Stone’s silence that tells the most resonating backstory. Years ago, Stone (a presumably single mother) lost her young daughter to a playground accident. Since then, Stone has been adrift, not unlike an untethered astronaut, with no emotional anchor to cling to. Space serves as the physical embodiment of Stone’s internal emptiness – at once comfortingly silent and beautiful in its capacity for self-reflection, and simultaneously a merciless and cruel killer if one opens oneself to it completely. Here, Cuaron uses sound (or the lack thereof) to spectacular effect: unlike with J. J. Abrams’ Star Trek: Into Darkness (wherein Abrams confesses in a Blu-Ray featurette that he initially wanted to have space be silent but ultimately felt unable to depict space battles without the sound of explosions) Cuaron deliberately lets some of the space action happen without sound and even with a minimum of ominous music. This has the effect of augmenting the alien, unearthly, and inhuman quality of space as a euphemism for emotional purgatory.

In this metaphor, Kowalski is the cautionary tale: although, Clooney plays him as singularly self-assured and alive, the price of his space-faring confidence is a man with a thousand and one entertaining party stories and no real personal connections. Kowalski’s is a life devoted to breaking an entirely meaningless space-walk record that no one else really cares about. Kowalski’s death hurts because he dies for the noble cause of saving Stone’s life, but also meets the end ofhis life empty and without having ever found a way to leave space behind and rejoin the living on Earth.

Meanwhile, Stone’s journey back to Earth requires her to overcome both physical and emotional obstacles and to do so alone; both are thrilling to watch. We are as equally on-edge over Stone’s space walk 100 kilometres to a distant space station in the face of an oncoming debris storm, as we are invested in Stone’s eventual decision to finally resume living. Despite my best efforts, the scene in the Soyuz with the spectre of Kowalski had me choking up.

If anything, the parallel between space and purgatory is a little heavy-handed, but since I’ve been in a headspace recently where I think movies need to be a little less subtle in their symbolism if they are to work as commentaries, I’m not going to hold it against Gravity. And that’s even though I found the final scenes with Stone literally crawling out of the mud and water in order to rejoin the land of the living about as subtle as a sledgehammer.

No, my issues with Gravity have more to do with where I think it was a victim of its own high-concept ambitions. Mainly, there are occasions where Gravity gets lost in placing symbolism over a good story. For example, the narrative arc of Gravity necessarily results in both of the film’s two main characters starting out as some pretty stereotypical tropes: the heroine as a terrified damsel-in-distress and the hero as a dashing space cowboy ready to save her. Also, they kill the movie’s only brown person within fifteen minutes, and the only time you see him is as an imploded corpse. Even the fact that Gravity is really Ryan Stone’s heroic journey does little to subvert the rather disturbing gender dynamics that comes with watching Sandra Bullock impotently hyperventilate for a good 60% of the movie.

Another problematic scene is when Ryan Stone, having made it to the International Space Station thanks to Kowalski’s self-sacrifice, feels the desire to live for the first time after having nearly suffocated to death in her space suit. She almost animalistically rips off her space suit, revealing Sandra Bullock’s lithe body clad only in a dark green tank-top and black spandex boy-shorts. The way the camera pans over Sandra Bullock’s naked arms and legs feels decidedly sexual, which is made all the more creepy when Bullock slowly pull her body into a foetal position and slips off to sleep with her oxygen tubing serving as a visual umbilical cord. It’s a whirlwind of female symbolism that takes us from dehumanized to hypersexualized to infantilized all in about a two minute span. Again, we get what Cuaron is doing: this is the first time that Ryan Stone appears recognizably human (rather than a giant white spacesuit marshmallow), and the audience is supposed to feel Stone’s own reconnection to her body as she is emotionally and physically reborn after having left the harshness of space. But, really? Even in this otherwise highly feminist science fiction story, we still have to contend with male gaze bullshit?

This scene is made all the more disconcerting by the unavoidable fact that it is wildly unrealistic. Boy shorts might be good enough for a Maxim-inspired space photoshoot, but it turns out they’re not standard NASA-issue underwear. Actual astronauts wear this (and also catheters):

Sure, this is just a movie, where artistic license rules the day. And, the scene where Ryan Stone rips out her own catheter in order to feel more alive might have been a bit too much for American moviegoers.

Nonetheless, for a film rooted so deeply in the world of contemporary science, Gravity demands some pretty substantial leaps of faith — ones that are kind of unnecessary if not for Cuaron’s desire to shoe-horn into the movie certain visuals. In addition to Stone as embryo, we are also treated to a scene where she cries and her tears float up into the zero-gravity cockpit of the Soyuz as their own untethered bubbles of pure sadness. Visually striking for the 3D moviegoer, I’m sure, if not for the surface tension of water which causes tears to stick to skin in a zero-G environment, creating an ever-expanding goggle of water.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4BbuOn–ERI

Neil deGrasse Tyson lists several other ways that Gravity is unscientific, and (in addition to the underwear) he touched on another point that I found equally distracting as the boyshorts: how did a biomedical engineer with only 6 months of space training and who couldn’t land the escape pod in a flight simulation ever make it into space? Considering that manned spacewalk missions cost millions of dollars, did it make sense for NASA to launch an unskilled civilian into orbit simply to install a circuit board (a task that she could conceivably direct from the safety of Houston mission control)? Why is a biomedical engineer even installing a piece of hardware into the Hubble in the first place — biomedical engineers don’t really do that? And, if Stone was so unprepared as to not know to stop panting in order to conserve oxygen, how did she navigate her way around the control panels of the Soyuz and the Shenzhou escape capsules with such ease?

In the end, I want very badly to love Gravity. But I don’t. I like it and it’s good, but I don’t love it. Gravity is kind of inspired – kind of – but when I sat back and thought about it, it also felt like one giant homage to a bunch of existing science fiction movies and anime that I’ve already seen, many of which have done the idea of Gravity better than Gravity does.

In the end, Gravity feels less like a complete science fiction movie with its own thoughts and ideas, and more like a vehicle for chaining together several half-formed ideas between “scenes that Cuaron really wanted to shoot” into a two-hour space. It feels like it’s trying a little hard. A little too hard. I think that the smartest movies are those that make the act of commentary appear both obvious and effortless; it is on this latter point that Gravity fails.

Thus, I can’t help but think that Gravity is getting kudos less because it’s good, and more because it’s better than everything else. The science fiction bar is currently set so low, that it makes Gravity shine. When the last political science fiction movie is Elysium – and most are more along the lines of Riddick – audiences and critics alike will love a movie like Gravity not necessarily because it’s objectively good, but rather because it’s refreshingly not-patronizingly-stupid. Gravity hearkens back to a time when science fiction was a genre of fun with a side order of political message, but compared to astoundingly intelligent science fiction of bygone years, it seems like mostly echo.

But, if that’s the case, than we should be less interested in Gravity itself and more preoccupied in the vacuum that surrounds it. If so, than maybe we are all Ryan Stone — science fiction nerds lost and spinning in the emptiness of a science fiction vacuum looking for something to hold on to. Maybe we are, all of us, in mourning of the death of a genre. Maybe the take-home message from Gravity isn’t just about grief and life, but also that Hollywood needs to stop making a bunch of science fiction crap that insults the entire movie-going audience, and instead make something worthy of nerdy passions. Something that can bring science fiction back to life. Something that doesn’t just suck.

Yes, I’m looking at you, Vin Diesel.