This post is broken into two parts for the sake of length:

- Anti-Asian Bias in College Admissions?: Part 1 – An improper comparison

- Anti-Asian Bias in College Admissions?: Part 2 – In support of affirmative action

Searching for “anti-Asian bias”: evidence of its existence

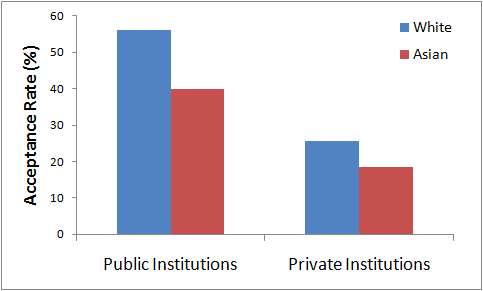

Espenshade presents data showing that acceptance rates to public and private institutions are universally lower for Asian American applicants compared to White applicants. I have graphed the appropriate data from Table 3.3 of Espenshade’s study below:

These data are striking. Neither Whites nor Asians benefit from affirmative action, and Whites and Asians share similar class distributions. Yet, Asian applicants are roughly 10% less likely to be accepted to private colleges, and nearly 15% less likely to be accepted to public institutions, compared to their White counterparts. The decreased acceptance rate holds true despite the fact that Asians are far less likely than applicants of other races to apply to public institutions — yet, unlike with the Black and Latino populations where reduced applicant rates explains, at least in part, high acceptance rates, the same is not true for Asian/Asian American applicants.

By all rights, since neither White nor Asian applicants benefit from affirmative action, our acceptance rates should be about the same.

All else being equal the reduced applicant rates could be due to one or a combination of the following explanations:

- Asian applicants, on the whole, have poor “breadth” qualifications that reduce the quality of their applications, e.g. music, art, a second language, etc.

- Asian applicants tend to be first and second generation, whereas White and Black applicants tend to be third, fourth or higher generation Americans (see Table 3.6 on page 7), making Asian applicants less likely to benefit from high acceptance rates for legacy students (Table 3.1 on page 2).

- Asian applicants are more likely to be international, and do not benefit from higher “in-state” or “domestic” acceptance rates.

- There is a currently unaddressed anti-Asian bias in the admissions process.

Most of these possibilities are not addressed (or debunked) by Espenshade’s study. Thus, at this time, it’s possible to conclude that there is anti-Asian bias in the admissions process, but it’s not the kind of anti-Asian bias that has been used to launch attacks against affirmative action. Instead, Espenshade’s data suggests that there Asian/Asian American applicants might face unequal treatment, compared to White applicants, when applying for institutions of higher education.

Perhaps this manifests as admissions boards wanting to limit the size of their Asian American student population and therefore specifically choosing White applicants over similarly-qualified Asian applicants. Alternatively, perhaps we’re seeing a manifestation of an internalized (and institutionalized) model minority myth which makes it more difficult for Asian applicants to demonstrate “breadth” qualifications (that are nonetheless present in the application) because we are being perceived by the admissions review board as math, science or engineering nerds. Regardless, the possibility that Espenshade’s data are uncovering evidence of anti-Asian bias in the admissions process to public and private colleges warrants further study.

In support of affirmative action

Studies like Espenshade’s have been used by right-wing conservatives to attack affirmative action. And certainly, Espenshade’s data show that acceptance rates are not the same between under-represented and well-represented racial groups. But the question remains: should those rates be equal?

Proponents of ending affirmative action argue that each applicant, regardless of race or class, should have the same acceptance rate as any other applicant. And this might make sense — if applications could really be equally judged across race and class. However, as I’ve mentioned, debate rages on as to whether so-called “standardized” tests are truly standardized, or if they suffer from cultural bias. Without a federalized public high school system, the meaning behind high school GPAs also vary from district to district, and from state to state. In other words, getting straight A’s in one school might not get you straight A’s in another.

In addition, being from an upper-class background affords opportunities that lower-class applicants don’t have access to. Applicants from wealthy families can afford to enroll in expensive prep schools that specifically train students to get into college — even if they aren’t necessarily smarter than the poor kids who can’t afford private school tuitions. In addition, wealthy applicants can afford to pay the expensive application fees such that they can apply to multiple schools; poor students are limited to applying to schools with low application fees or to a fewer number of schools, reducing their chances of admittance.

Affirmative action is intended to address the disparities and unequal opportunities for applicants, and to make admission to higher education more accessible for disadvantaged applicants. But, more importantly, affirmative action policies exist to make a more diverse student body.

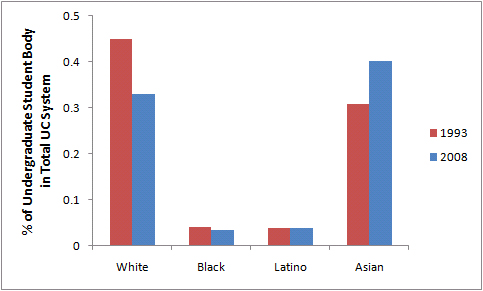

Consider this: in the state of California, where affirmative action practices have been out-lawed, the racial demographics in state colleges and universities have only become less representative of national demographics. Comparing students by race/ethnicity in the total UC system in 1993 against the same data collected in 2008 (Table 7k), we see that Asian American students now make up more than 40% of all undergraduate students, while the percentage of White, Black and Latino students decreased over that time period.

Not only are underrepresented minority groups languishing without affirmative action in place in the California school system, but students of well-represented racial/ethnic groups are also suffering due to these disproportionate student populations. Anti-affirmative action fundamentalists and fervent Asian American nationalists might applaud that nearly half of UC students are Asian American, but I propose that this actually diminishes the quality of education that our Asian American students have access to.

Academia is about developing a forum of discussion, argument and debate; where a free-flowing exchange of ideas can take place. This can only occur in a diverse populace where students are exposed to unique ideas originating from a multiplicity of different perspectives and backgrounds. When nearly half of all people that a student can meet in class come from a similar background, the student loses the opportunity to have his or her worldview challenge. Without that kind of an education, one must question how prepared these college students are to face a racially, ethnically, and economically diverse reality upon graduation. Perhaps more so than any other institution, colleges and universities need affirmative action in order to survive.

Summary

Getting into college isn’t easy; and it’s not supposed to be. We have to recognize that no one can — or should be allowed to — skate into college, and that the same difficulties and frustrations you feel with the admissions process of your favourite undergraduate institution are felt by high school students across the country, regardless of race, class or gender. When you get in, you feel on top of the world; but if you don’t, often you feel like the process was unfair and biased.

The argument against affirmative action in colleges is too-often made by groups who feel entitled to higher education, and who can’t abide by the fact that they should have to work for it (and to prove themselves) just like everyone else. And the classic “anti-Asian bias” argument that touts facts and figures comparing acceptance rates for Asian/Asian Americans against those of minority groups underrepresented in higher education only pits minority groups against one another while propping Asian Americans as the token “model minority”.

Rather than to blindly accept a charged, politically-motivated, and misleading interpretation of college admissions data (often collected in good faith by well-meaning scientists like Espenshade), it’s important to consider studies like those presented above carefully. I think there is evidence here that Asian Americans experience anti-Asian bias in the college admissions process. Nothing to date addresses the unequal acceptance rates between White and Asian students, despite a lack of difference in treatment by affirmative action policies, and despite similar application rates. More studies must be done to figure out what’s behind those disparate admissions probabilities.

But does that mean that Asian Americans aren’t benefiting from higher education? Hardly. Around the country, Asian Americans are better represented on college campuses than we are in the national population. And while some Asian ethnicities remain underrepresented, on the whole, our community is churning out well-educated degree-holders who are entering the skilled workforce en masse.

So, if you’re an Asian American high school student applying to college, remember the following: the admissions process will be difficult, but with decent grades and SAT scores, and with diverse interests in music, drama or another language, you’ll find a great college. Ask for help in preparing your application — clearly, there are lots of Asian Americans out there who have been through this process. And, above all, don’t limit yourself to the elite schools that are receiving tons of Asian American applicants: make sure to apply to a few less well-known or public schools, even just as a back-up.

Because here’s the final piece of advice I have, and it’s one that some people don’t want to vocalize: In the end, it’s not about what school you get into (or how you get in, whether by affirmative action, legacy, athletic scholarships, or if you speak six languages and are a world-renowned kazoo player) — it’s about how well you succeed once you get there.

The rest of it’s just getting your foot in the door. What happens after that is up to you.