Nearly 25 years ago, California voters passed Proposition 209, a state constitutional amendment that barred public institutions (such as public universities and state agencies) from considering race, gender, or ethnicity in admissions, hiring, or contracting. In so doing, California became one of only eight states in the US to ban the use of race- or gender-conscious affirmative action.

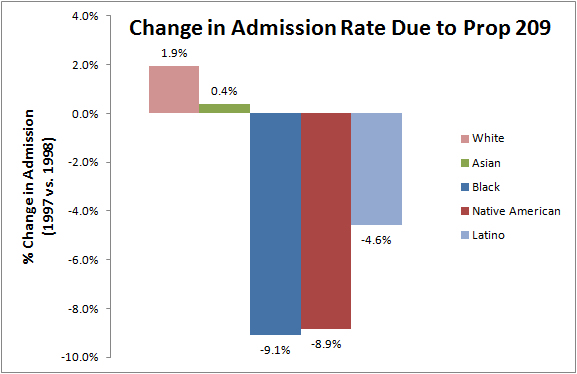

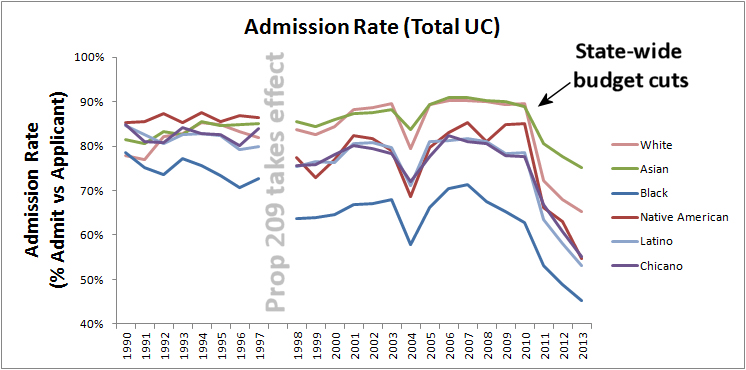

The aftermath of Proposition 209 was immediate and stark. A year following passage of Proposition 209, Black, Chicanx, Latinx, and Native admission rates to UC schools fell precipitously — by nearly 30% at some campuses — and remained depressed for the more than two decades that followed. Barriers in government contracting also led to an estimated annual loss of $1 billion in contract dollars by minority- and women-owned small businesses.

In the nearly 25 years since Proposition 209’s passage, the loss of affirmative action has only served to further crystallize the ways in which structural inaccess disproportionately excludes Black and Brown communities. We have seen an erosion of Black and Brown enrollment in California’s public universities, and fewer state contracts awarded to minority-owned businesses. Proposition 209 was clearly decided in error, and it is time for a new generation of California voters to be empowered to correct the persistent exclusion of so many Californians of colour.

To understand why we need affirmative action, we must first understand affirmative action’s history. First advanced in the 1960’s, affirmative action was a radical solution advanced in acknowledgement of the wildly disproportionate and devastating impact of white supremacy on the Black community in denying access to higher education and the workforce. Affirmative action was proposed as a way to take ‘affirmative’ steps to prevent such racial discrimination and ensure equal employment of Black Americans and other people of color; and later, women.

In other words, affirmative action is — at its philosophical core — about redress for centuries of structural racism in America that has culminated in a deeply unequal society for Black and Brown people. It fundamentally asserts that a false veneer of ‘color-blindness’ can never achieve racial equity so long as it ignores the (often, far too fresh) scars of white supremacy, anti-blackness, and systemic racism in this country.

More recently, universities have advanced a separate (arguably, more corporatized) argument in favor of affirmative action — the diversity rationale. Schools now also assert that, as institutions of higher learning, they have a ‘compelling interest’ to foster a diverse student body. Studies routinely find that a diverse student population improves student outcomes for all students. Universities’ compelling interest to achieve a diverse student population has been reaffirmed by the nation’s Courts to justify the (limited, narrow) use of race and other background information in assessing students during college admissions as part of a larger holistic review process.

Affirmative action is an imperfect solution to one of America’s oldest systemic problems. It is not, by any means sufficient, to fully address the wide-reaching impacts of structural racism in America – as recent weeks have profoundly illustrated.

But, so long as racial justice continues to elude this country in such profound and unequal ways, affirmative action is arguably still necessary; and so, we must continue the work of restoring it in the state of California.

The simple fact about affirmative action is that both rationales compel, albeit in different ways. As an academic and educator, I believe in fostering a diverse learning environment for my students, and to help prepare them for life in an increasingly multiracial, multiethnic, multicultural world. Students deserve not just to be lectured at, but to be able to build community with one another — and that starts by learning to interact with, and learning from, peers of different backgrounds.

More fundamentally, however, I believe that higher education should be fully accessible to students regardless of race or ethnicity. Many of this nation’s institutions of higher education were built out of slavery. There is quite simply no excuse for our society to continue to argue against full access for Black and Brown students to these same institutions — especially given that most schools historically resisted higher education access for Black and other non-white candidates as a strategy to reaffirm white (male) supremacy. There is no moral argument in favor of continuing such a tradition of gatekeeping and exclusion.

As the impact of Proposition 209 on California’s students and small businesses became increasingly clear in the years following its passage, activists quickly mobilized to try and enact legislation that might reverse it and help stymy its devastating effects.

In 2012, activists partnered with California State Senator Ed Hernandez to advance Senate Constitutional Amendment 5 (SCA5), which would repeal Proposition 209 and enable voters to re-allow consideration of race or gender in recruitment, retention, and admissions programs in California’s public universities. Although SCA5 passed the California State Senate, it was soon withdrawn after it faced harsh (and often inaccurate) backlash from a nascent, conservative Chinese American grassroots movement that coalesced around their vehement opposition to affirmative action.

Affirmative action’s Asian American opponents contend that affirmative action discriminates against Asian American students in college admissions. They fear that any consideration of an applicant’s race amounts to a de facto racial quota, and that in practice this would unfairly disadvantage Asian American higher education admission. In extreme cases, affirmative action is likened by some conservative Chinese Americans to Jim Crow laws and the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act.

To argue against affirmative action as an Asian American is to argue a (flattened) narrative of Asian American racial-cultural exceptionalism and corresponding entitlement, while ignoring how such model minority tropes weaponize the Asian American experience in service of anti-blackness. Perhaps this is why surveys routinely find that nearly two-thirds of Asian Americans continue to support affirmative action.

These comparisons utterly misrepresent the facts. There is lengthy Supreme Court jurisprudence around the issue of affirmative action, and how it may be legally applied. Race may only be considered narrowly, and in a non-determinative way –that is, it may not add context but may not be the deciding factor in an admissions or hiring decision. Institutions that incorporate affirmative action may not employ a quota system — that is, reserve some seats for candidates of a certain background. Arguments against affirmative action based on the assertion that it will be practiced illegally are disingenuous.

Contrary to what affirmative action’s opponents suggest, affirmative action does not meaningfully harm Asian American admissions, nor did Proposition 209 meaningfully improve it. In total, Asian American admissions were stagnant following passage of Proposition 209 — even as Black, Native, and Latinx admissions fell. (Instead, it was largely white admissions that improved following Proposition 209’s passage). Meanwhile, some already-marginalized Asian Americans — such as Filipinx Americans — saw their admission rate to some UC campuses further drop by nearly 10%.

To argue against affirmative action as an Asian American is to argue a (flattened) narrative of Asian American racial-cultural exceptionalism and corresponding entitlement, while ignoring how such model minority tropes weaponize the Asian American experience in service of anti-blackness. Perhaps this is why surveys routinely find that nearly two-thirds of Asian Americans continue to support affirmative action, and why over 150 Asian American advocacy groups joined together in 2016 in an open letter to support affirmative action.

Earlier this year, efforts to repeal Proposition 209 got a second wind with the introduction of Assembly Constitutional Amendment 5 (ACA5), which – like its predecessor – would allow voters to decide to restore affirmative action in this state. ACA5 is authored by Assemblymembers Shirley Weber, Mike Gipson, and Miguel Santiago and is supported by a multi-racial coalition of activists, including – significantly – many progressive Asian Americans (including the author of this blog).

Progressive Asian Americans, like myself, have been entrenched in this fight for years, working to highlight a progressive counternarrative to the highly-visible anti-affirmative action stance of some conservative Chinese Americans. As progressives, we seek to correct the factual record around how Asian Americans discuss affirmative action, and how our history is sometimes erroneously deployed in this discourse. We advance a message in support of affirmative action built upon precepts of diversity, acceptance, racial justice, and inter-community coalition-building.

Today, we have reason to celebrate. Six years after the disappointing defeat of SCA5, ACA5 made it to the Assembly floor and received 58 bipartisan votes — including yes votes from most members of the API California Legislative Caucus — ensuring its passage. ACA5 now faces a floor vote in the California State Senate next week. If it passes that, it will appear on the ballot in the November general election for voters to consider.

California is poised for the first time in nearly 25 years, to restore affirmative action and to finally take steps to remove structural barriers to higher education and economic access that face many Black and Brown Californians.

And so, California is poised for the first time in nearly 25 years, to restore affirmative action and to finally take steps to remove structural barriers to higher education and economic access that face many Black and Brown Californians.

Affirmative action is an imperfect solution to one of America’s oldest systemic problems. It is not, by any means sufficient, to fully address the wide-reaching impacts of structural racism in America – as recent weeks have profoundly illustrated.

But, so long as racial justice continues to elude this country in such profound and unequal ways, affirmative action is arguably still necessary; and so, we must continue the work of restoring it in the state of California.

Learn more about the fight to restore affirmative action in California, or donate and get involved.