By Guest Contributor: Frances Huynh

Read the first of this series: “The Gentrification of Los Angeles Chinatown: How Do We Talk About It?”

* * *

A quietness lingers as we set up shop. Empty streets fill with the jostle of clothing racks. The multiple clicks of stoves turning on. The soft smack of noodle to plate. Doors open.

On the top floor of Far East Plaza stands 香港美食坊 (J&K Hong Kong Cuisine), a 茶餐廳 (cha chaan teng — a specific type of Hong-Kong style diner). Cantonese shows play on the television in the background, while seniors chat with friends and family at the tables all around. For many of Chinatown’s residents, it is one of a handful of go-to restaurants in the neighborhood for plates of Cantonese comfort food. Peter, a long-time resident, enjoys eating their 海鮮粥 (seafood congee) and 水餃 (dumplings). “很平 (It’s very inexpensive),” Lee Tai Tai, another resident, says. The restaurant is an important community space, providing Chinatown’s seniors an accessible place to hang out and to socialize with friends over dishes reminiscent of those found in the homelands they immigrated from. They also frequent other small shops, including New Dragon, Zen Mei Bistro, and Fortune Gourmet Kitchen, in addition to larger banquet-style restaurants such as CBS Seafood Restaurant, Regent Inn, Full House Seafood Restaurant, and Golden Dragon.

Every morning Monday to Friday, Julie, who has lived in Chinatown for over thirty years, joins about sixty other seniors to eat at Golden Dragon, a longstanding Cantonese restaurant commonly frequented by residents and visiting families. She enjoys eating the healthy meals provided by the “senior nutrition lunch” program held there.1St. Barnabas Senior Services is a non-profit organization that provides free nutritious meals to low-income adults 60 years and older at fourteen congregate meals sites including Golden Dragon. There is a suggested donation. Afterwards, she walks home to her apartment several blocks away and spends the rest of the day listening to the radio and watching Hong Kong dramas. When dinner time comes, she walks to one of several restaurants in the neighborhood to buy what she considers “fast food”: convenient Chinese takeout. By then, she notes, time just passes by.

Changing Landscapes

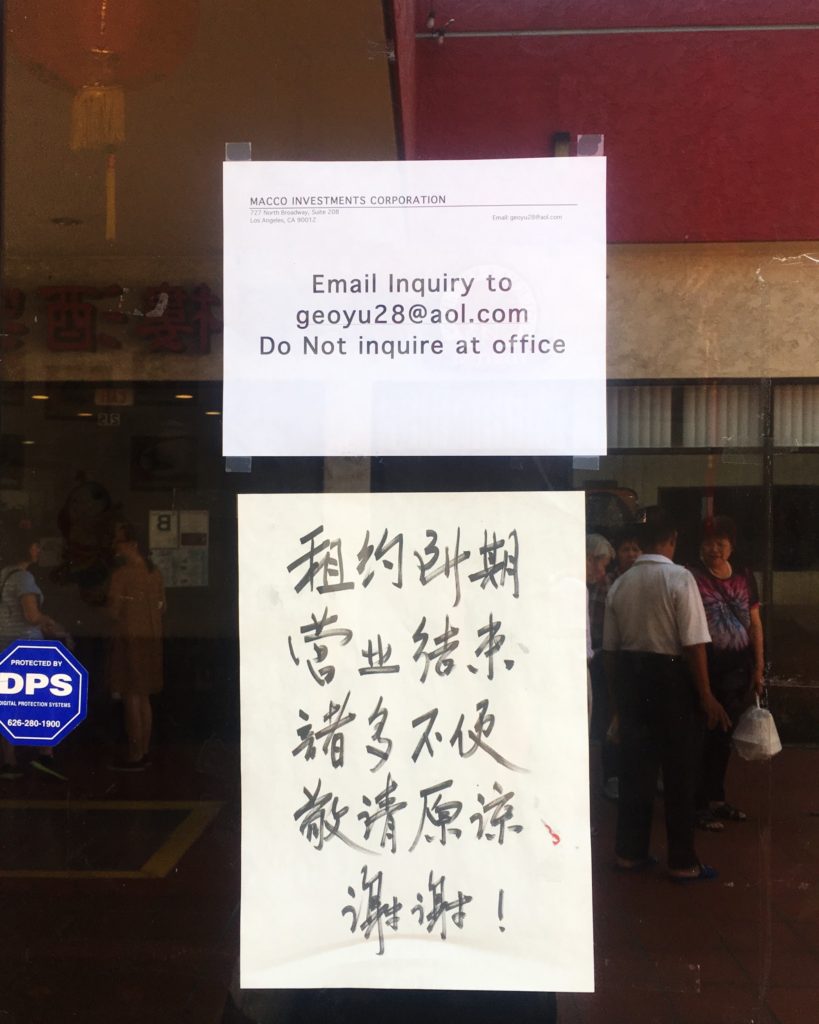

In the spring of 2013, Korean American restaurateur Roy Choi opened Chinatown’s first celebrity-chef-driven restaurant, Chego, after meeting with George Yu,2Spiers, “Chinatown’s Far East Plaza Is a Dining Destination Thanks to George Yu.” the vice president of the investment company Macco Investments Corp. that owns the Far East Plaza. Considered to be “the man pulling the strings,”3Farley Elliot, “Meet the Man Who Brought Chinatown’s Far East Plaza Back to Life,” March 28, 2016. Yu crafts his own vision for Chinatown by overseeing leasing at this commercial center.

Far East Plaza would transform into the nexus of the neighborhood’s changing culinary and business scene — #TheCulinaryGameIsStrongInFarEastPlaza.4The new wave of eateries often use the hashtag “#TheCulinaryGameIsStrongInFarEastPlaza” on Instagram. Over the next few years, Chego’s opening would bring an influx of similar “hot-ticket”5Spiers, “Chinatown’s Far East Plaza Is a Dining Destination Thanks to George Yu.” eateries and boutiques that cater to upwardly mobile professionals and creatives. According to Nguyen Tran of the former Starry Kitchen that opened in late 2013, Choi “shined a guiding light towards Chinatown”6Nguyen Tran, “How to Run an Illegal Restaurant,” September 27, 2017 and was “the catalyst that convinced us to consider [opening shop there].”7Lesley Balla, “Starry Kitchen Begins Serving in Chinatown This Weekend,” July 12, 2013. Ten months following Chego’s opening in May came the popular artisanal ice cream shop Scoops.8Eddie Kim, “How an Aging Chinatown Mall Became a Hipster Food Haven,” March 28, 2016.

As Chinatown began experiencing an uptake in attention by the culinary world, it also saw the influx of massive market-rate and multi-story projects. In 2014, billionaire real estate investor Sam Zell’s Equity Residential opened the six-story $93-million Jia Apartments,9Bianca Barragan. “Chinatown’s Jia Apartments Opens With Rents Starting at $1,690,” March 4, 2014. the neighborhood’s first luxury mixed-use (residential and commercial) development. Its website boasts of “a state of the art fitness center,” “stunning pool and spa,” “9 Foot ceilings,” and “gourmet kitchens.”10Equity Apartments, “Jia Apartments in Chinatown,” accessed July 25, 2018. In the midst of a nationwide affordable housing crisis and growing homeless community in the city, monthly rents at Jia start at $1,936 for a 571 square feet studio and $2,715 for a 2-bedroom apartment. All the while, down the street on Broadway, low-income tenants, many of whom are elderly and disabled, face poor housing conditions. Sharing a communal kitchen and bathrooms, they live in cramped single-residence occupancies that line the top floor of commercial buildings. At Metro @ Chinatown Senior Lofts on nearby Spring Street, fixed-income and low-income tenants fight an excessive 8% rent increase that tops a 3% increase last year. For many, a rent increase means being displaced and losing not only a physical home but the social network, resources, and sense of community that the neighborhood provides.

In November 2016, Eddie Huang, well-known Taiwanese American chef and author of the autobiography-turned-TV-show Fresh Off the Boat, also brought his New York-based BaoHaus into the retail space formerly occupied by Pok Pok Phat Thai,11Farley Elliot, “Eddie Huang’s Baohaus Slinging Buns Right Now in Chinatown,” November 7, 2016. one of two Thai restaurants in Chinatown owned by the white Andy Ricker. When Huang considered opening a BaoHaus in New York Chinatown a year later,12Serena Dai, “TV Chef Eddie Huang Plans New Outpost of Baohaus in Chinatown,” July 27, 2017. he claimed to have “DELIBERATELY pulled out when [he] found out that the developer would most likely tear down the buildings around [him] within 10 years and that [he’d] be contributing to the rise in rents if [he] went in.” Yet, his shop remains open in a gentrifying Los Angeles Chinatown. For him, “restaurants have the responsibility of being cultural distribution centers”13Besha Rodell, “TV Chef Eddie Huang Plans New Outpost of Baohaus in Chinatown,” November 30, 2016. to their customers, but how are they responsible to the communities they move into?

In 2014, the Filipino American chef Alvin Cailan, who was popularized by Eggslut in Downtown’s Grand Central Market, opened Ramen Champ,14Julie Woflson, “Ramen alert: Eggslut’s Alvin Cailan opening Ramen Champ in Chinatown,” December 19, 2014. which then switched owners not long after. In early 2016,15Farley Elliot, “Unit 120 Is Alvin Cailan’s Blank New Canvas for LA’s Next Great Restaurant,” Jan 20, 2016. he would go on to open Unit 120 in the space of the former Pho 79.16Danny Jensen, “Exploring LA’s Growing Filipino Food Movement with Alvin Cailan of Eggslut,” January 3, 2017. This “culinary incubator” rotated up-and-coming chefs who wanted to experiment with restaurant concepts, such as the Filipino brother duo LASA who took over the space after a year.17Hillary Eaton, “Lasa, a Filipino pop-up restaurant, takes over the Unit 120 space in Chinatown,” January 18, 2017.

Waiting in Line

Lines stretch out the doors of Howlin’ Ray’s. On the days that the restaurant is open, Far East Plaza sees crowds of young and middle-aged individuals waiting on average two to three hours for a chance to taste this trending food. Julie, Pauline, and other residents wonder why people would wait that long for chicken. With that amount of time, they could attend to errands or go grocery shopping instead. Longtime residents and seniors are outnumbered by the people waiting to eat at Howlin’ Ray’s, Chego, Lasa, or Baohaus. There seem to be fewer of them walking around the plaza nowadays, especially with the closure of two-floor herbal shop Wing Hop Fung in early 2016. 18CCED Facebook, “Wing Hop Fung is closing…” February, 24, 2016. The white couple who owned the Nashville-style hot chicken food truck, Johnny Zone and Amanda Chapman opened the Howlin’ Ray’s brick-and-mortar in Chinatown on April 2016.19Howlin’ Rays’, “Chinatown Opening!” April 26, 2016. (Rachel Kuo offers a solid critique of a similar pair of white restauranteurs in the South who profit from selling hot chicken to primarily white and upper middle-class communities. She calls them “white proprietors of ‘Black culture.’” Read it here, in addition to Rachel L. Martin’s historical analysis of Nashville’s discriminatory urban planning practices and racial politics all in relation to hot chicken.)

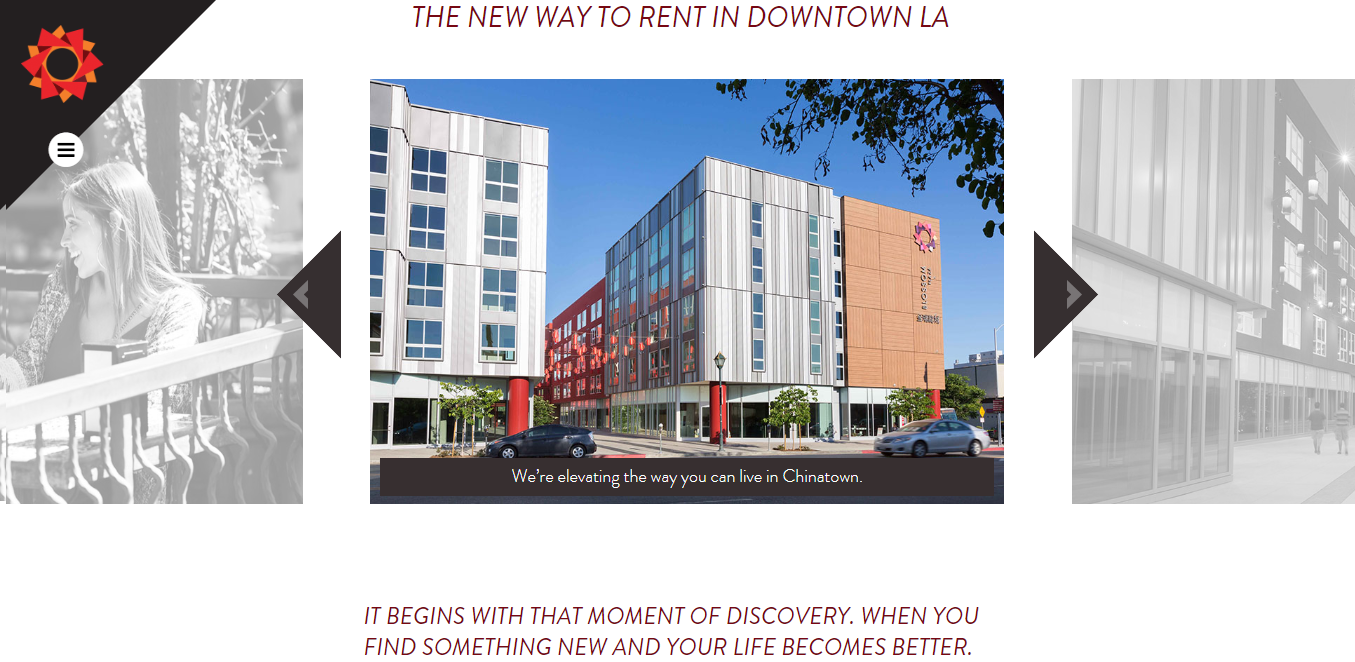

In that same year, the nearby $100-million Blossom Plaza2019. Steven Sharp. “Blossom Plaza Headed Toward the Finish Line,” January 5, 2016. turned on its strings of red lantern lights and flashed welcoming marketing signs that read “A NEW ERA IN DOWNTOWN LIVING” — for who? — and “CONQUER IT” — conquer what? While approximately 20% of its 237 units had been set aside as “affordable housing,” an effort likely to be applauded by city officials and developers as being generous, this was far from enough to meet the growing demand. Over 2,300 applications were sent in for those mere 53 units. With little to no income or resources, a significant number of seniors who live in Chinatown rely on Supplemental Security Income (SSI), a federal assistance program, to provide for themselves financially. In 2018, individual seniors in California receive $910.72 in SSI payments each month, while couples receive $1,532.14.21United States Social Security Administration, “Supplemental Security Income (SSI) in California,” 2018. This gets them nothing at Blossom Plaza, where it costs $2,398 for a 1-bedroom apartment.22Blossom Plaza, accessed August 7, 2018. Projects like this one market “a whole new level of living”23Blossom Plaza, accessed August 7, 2018. in Chinatown to middle-to-upper-class individuals. Yet, the reality is that the neighborhood has one of the lowest median household incomes in the city. Who can afford this “new way to rent in Downtown LA”?

Residents and community members are demanding culturally competent healthcare and social services, community gathering spaces, fresh grocery markets, and quality low-income housing for Chinatown. However, more proposals have been made to build majority, if not all, market-rate developments across the neighborhood. Neighboring Blossom Plaza is the Capitol Milling project that is in the midst of construction. The development firm S&R Partners, which belongs to the wealthy Riboli family who owns San Antonio Winery, plans to open a microbrewery, restaurants, and offices.24Blanca Barragan. “Checking in on the Chinatown’s Capitol Milling project,” June 13, 2017. The family has also proposed the widely opposed Elysian Park Lofts across the street. It includes 920 market-rate apartment units, 17 live/work lofts, and 17,941 square feet of retail space. Other proposals include the ridiculously out-of-place Atlas Capital Group’s College Station Project, which includes 770 apartment units and 51,390 square feet of commercial floor area for a market, restaurants, and retail space; and architectural firm Studio Gang’s 26-story apartment and hotel tower, which includes 300 apartments, 149 hotel rooms, and retail. In a community where the median household income is $18,657 and 95% of the population are renters,25Wendy Chung. “One Chinatown.” 2016. who can possibly afford to call these places home?

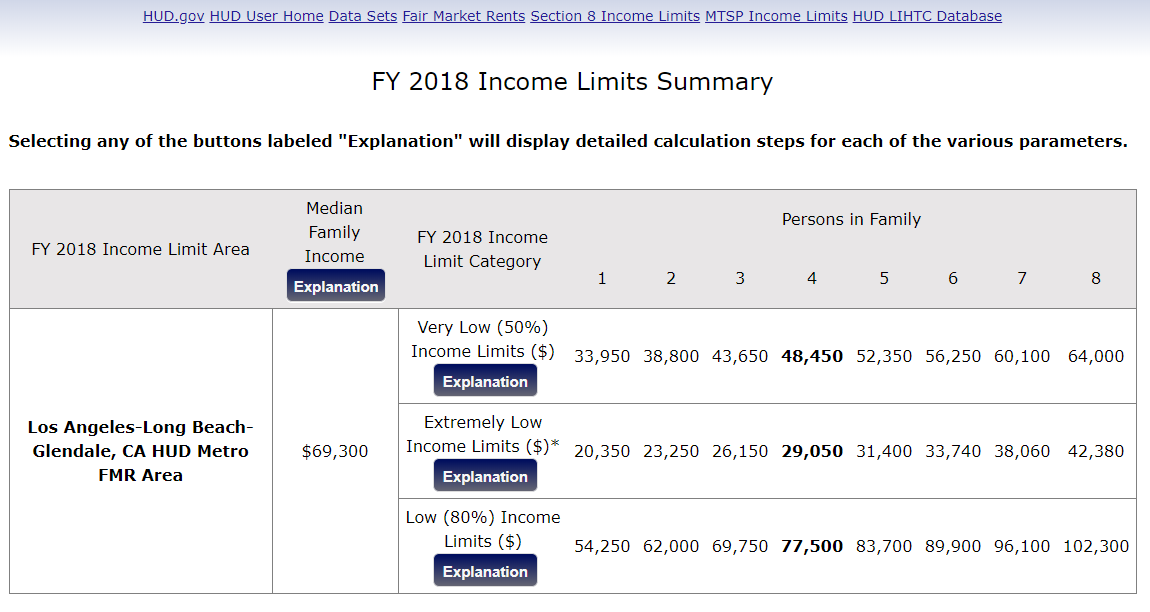

If these developments were truly meant to house Chinatown’s working-class residents, 100% of their units would be truly affordable. What Los Angeles currently considers “affordable” for housing is not affordable enough for Chinatown residents and a large number of low-income families and individuals. Based on federal income limits, levels of affordability are calculated based on certain percentages of area median income (AMI); Los Angeles county’s median family income is $69,300 for 2018.26U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, “FY 2018 Income Limits Summary” for Los Angeles-Long Beach-Glendale, CA HUD Metro FMR Area, FY Income Limits Documentation System, accessed April 16, 2018. To be eligible for units with these affordable housing thresholds, residents must have incomes considered “low” (80% of AMI), “very low” (50% of AMI), and “extremely low” (30%/50% of very low-income limit). A significant number of Chinatown residents have incomes that fall far below what is considered extremely low-income.

From Coffee Shops to Studios

It is not a coincidence that the influx of hip eateries, alongside art galleries, artisanal coffee shops, minimalist boutiques, breweries, micro hotels, and Skrillex’s OWSLA “pop-up” shop (it’s been over two years), in Chinatown occurs at the same that wealthy developers and investors are buying up land and looking to build mixed-use market-rate development projects that are unaffordable and inaccessible to the working-class. Or at the same time that longtime small businesses and low-income tenants are increasingly being displaced through drastic rent increases, evictions, and cash-for-keys tactics. Chinatown is being restructured by developers and city officials to house the upwardly mobile, generate profits for the rich, and displace the poor.

What we visibly associate with gentrification — the indie boutiques that sell shoes for hundreds to the corporate Starbucks — is undeniably part of a larger process of growing socioeconomic inequity in working-class communities of color. The new wave of eateries presumably cater primarily, if not solely, to the younger, upwardly mobile demographic of professionals and creatives that Downtown — and now Chinatown — developers, such as Izek Shomof, Tom Gilmore, and Goodwin Gaw market to and profit from. These are the commercial spaces that line developers’ visions of trendy urban destinations and the people who they want to move into their market-rate studios. We clearly see this with the Alpine Plaza building that was purchased by Shomof several years ago. Once occupied with Southeast Asian businesses, it now stands empty (except for the lone Salathai) and markets itself as “ARTIST WORKSPACE.” According to the GMPA Architects website, Shomof’s proposed project is explicitly “targeted to the millennial generation.”27GMPA Architects, “Alpine Street”.

In April 2018, Tom Gilmore closed escrow — completing the process of purchasing — on the property where Ai Hoa Supermarket and the next-door immigrant-owned photo studio, Cambodian restaurant, and video and gift store are located. A few years prior, he acquired adjacent property on the same block. While food bloggers enthusiastically celebrate the new wave of restaurants, community members fear that Gilmore will displace the longtime businesses to replace them with a hotel.

Improvements for Who?

Alongside several other wealthy property owners from Chinatown, Gilmore sits on the board of directors of the Chinatown Business Improvement District (BID), an entity that plays a disproportionately large role driving the decision-making processes of the neighborhood’s urban redevelopment. The same George Yu who is credited by chefs and owners of hip eateries for bringing them into Chinatown28Katherine Spiers, “Chinatown’s Far East Plaza Is a Dining Destination Thanks to George Yu,” May 3, 2017. is also the executive director of BID. Formally established in 2011, BID is completely funded by a mandatory fee paid by property owners in the commercial district of Chinatown to provide services that the city fails to do adequately or at all.29Ben Ehrenreich, “Off My Back,” May 16, 2001. This includes cleaning up trash, removing graffiti, holding special events (e.g., Chinatown Summer Nights), and maintaining streetscapes. Working with a budget of nearly $2 million, BID is also funded to privately police the neighborhood. With a funding and organizational structure that makes them “inherently undemocratic,”30Ben Ehrenreich, “Off My Back,” May 16, 2001. they are considered to be accountable to no one but themselves.

Collaborating closely with local governments and private investors — such as the ones who sit on their boards — Business Improvement Districts are a tool of gentrification and participate directly in the increasing criminalization and privatization of urban cities. In Downtown Los Angeles, Business Improvement Districts hire private security who have been known to intimidate and hurt the homeless community. BID-employed security essentially exist to “maximize the profitability of the areas they patrol.” They work to make neighborhoods attractive for consumerism and investment, targeting those who stand in the way. In Chinatown, these “red shirts” have harassed informal street vendors, musicians, and homeless individuals who are integral residents of the community. To “keep crime down in the neighborhood,” Yu also works closely with the Los Angeles Police Department.31Jean Trinh, “The Past, Present, and Future of Chinatown’s Changing Culinary Landscape,” February 28, 2017. BID is far from representative or accountable to the needs of the neighborhood. It actively participates in upholding a violent criminal justice system that exacerbates the community’s socioeconomic inequities. Yet, residents and small businesses alike have the power to hold them responsible for their actions.

Let’s Just Call It North Downtown

David Chang of New York’s Momofuku restaurant enterprise is the most recent celebrity chef to come to Chinatown. In January 2018, he opened Majordomo in what Matthew Kang of Eater LA dismissively calls “north Downtown,”32Matthew Kang, “David Chang’s Majordomo Opens Tonight: Here’s What to Expect,” January 23, 2018. a far side of Chinatown filled with industrial warehouses that another writer foresees becoming the next Arts District.33Farley Elliot, “Is Majordomo Already Changing Real Estate Fortunes in Far Chinatown?” April 19, 2018. The artwork of millionaire rape fantasy artist and Chang’s good friend David Choe decorates the restaurant’s bar area.

For Kang, “the conversation about the exact neighborhood of a restaurant isn’t as important as celebrating what the restaurant itself is doing.” With this framework, he divorces places that carry as much capital as Majordomo from their role in spurring real estate speculation and driving gentrification in Chinatown and surrounding communities. Like the developers who brand Chinatown as Downtown, writers often celebrate the bourgeois revival of the neighborhood and Asian American representation in haute cuisine while erasing the history, narratives, and issues of the existing immigrant community.

In an interview with Bill Simmons, David Chang describes how much thought he has put into selecting the location for Majordomo. “I remember thinking,” he recalls, “‘I feel like such a dope for not expanding to downtown L.A. … I’m not going to do that again.’ And it’s not just about — I don’t want to be a part of a gentrifying movement. It’s just about, how do we do something awesome that adds to the awesomeness?” Chang wants to be a “good neighbor”34The Dave Chang Show, “How Dave Chang Found the Right L.A. Location for His Restaurant Majordomo,” April 26, 2018. and wants to “add value” to the community he’s opened shop in. However, given his active role in gentrification, he can only be considered a good neighbor to the artists, entertainers, and property owners who will profit from the economic value that his presence creates.

The property on which Majordomo stands belongs to the Hong Kong-based Gaw Capital. Considered to be the 23rd largest private equity real estate firm in the world, the company is run by Goodwin Gaw and his billionaire family — the real life crazy rich Asians themselves. Located nearby on the same property is Apotheke, a pricey cocktail bar that opened up a few weeks prior to Majordomo. With a location already in New York’s Chinatown, this new west coast Apotheke has driven journalists to exclaim, “At this rate, Chinatown will soon rival downtown Los Angeles’ Arts District as a food and drinks destination.”35Tony Chen, “Three new bars aim to reinvigorate the drinking scene in L.A.’s Chinatown,” September 28, 2016. Hoping to follow suit with their own second location is the music venue Baby’s All Right which hails from a gentrifying Brooklyn.36Bianca Barragan, “New York music venue Baby’s All Right coming to Chinatown warehouse,” July 11, 2017.

People are banking on the inequitable urban revitalization of the neighborhood with their entertainment, alcohol, and artwashing. Nearby, restaurateur and hotelier Dustin Lancaster has already opened up Oriel wine bar and a second post for Highland Park Brewery in Chinatown. Early in the year, Into Action, a social justice-themed art exhibit “drew thousands of left-leaning fans to new gallery spaces.”37August Brown, “In a changing Chinatown, the new dance-focused Secret Project aims to make it a festival destination,” August 22nd, 2018 A commercialization of social justice movements, the event’s complicity in artwashing was critiqued by anti-gentrification groups. To top everything off, organizer of the Electric Daisy Carnival, Insomniac, plans to hold a two-day electronic music festival called Secret Project at their Factory 93 warehouse this upcoming October. A promoter for the event enthusiastically raves how it will “show the rest of the city what Chinatown has to offer.”38August Brown, “In a changing Chinatown, the new dance-focused Secret Project aims to make it a festival destination,” August 22nd, 2018 If long-term community displacement is ultimately what these spaces have to offer, we must fight back and say no.

Asian American Chefs and Their Role in Gentrification

In her critical analysis of David Chang’s recent Netflix series Ugly Delicious, Rachel Kuo points to Brandon Jew of Mister Jiu’s in San Francisco Chinatown to emphasize how second-generation and third-generation Asian American chefs can contribute to the gentrification of low-income Asian immigrant communities. She poses questions that Los Angeles Chinatown’s restaurateurs, not only those serving Chinese cuisine, need to answer: “What happens when the Chinese food that people can feel pride in isn’t affordable by working class immigrant populations? What happens when Chinese food is valued only when it caters to a more elite class of Asian Americans and other clientele who can afford the uptick in price?”

Kuo goes on to say: “Jew, like Chang, is styled as ‘ethnic haute’ cuisine; both capitalize upon their ‘ethnic expertise’ as culinary ambassadors of non-white cuisines for white audiences.” She cites food scholar Krishnendu Ray, arguing that “the ethnic cook is remade and promoted through proper skills, habits, and training to fit ‘middle-class aspiration and upper-class consumption.’” As gentrification worsens an already widening income gap, health disparities, and socioeconomic inequities, we should ask ourselves who in Chinatown can afford and feel welcomed in spaces that serve $4 baos or $32 Cave Aged Butter & White Sturgeon Caviar.

Oftentimes, the changes and displacement associated with gentrification are seen as inevitable, especially in order for a city to progress and grow. However, presenting gentrification as the “revitalization”39Farley Elliot, “Inside the 20-Year Effort to Turn Chinatown Into a Thriving Cultural Center Once Again,” March 7, 2017. of a low-income neighborhood ignores how deeply unjust and unequal this process is. For Alvin Cailan, Chinatown is “just modernizing,” with “newer entrepreneurs [and] newer residents coming into the neighborhood.”40Jean Trinh, “The Past, Present, and Future of Chinatown’s Changing Culinary Landscape,” February 28, 2017. Roy Choi, on the other hand, doesn’t feel that Chinatown has changed, believing that older residents haven’t been pushed out.41Jean Trinh, “The Past, Present, and Future of Chinatown’s Changing Culinary Landscape,” February 28, 2017. These restaurateurs are often quoted as being empathetic toward and appreciative of the older generation of small businesses that continue to or used to exist in the neighborhood.6 However, they lack — or significantly fail to articulate publicly — a critical, nuanced understanding of Chinatown’s changes as being rooted in a larger process of inequitable economic development, one that values them but will eventually displace the older businesses that they try to honor. George Yu believes “everybody benefits” from replacing “underutilized” commercial properties with new businesses such as Cailan’s and Choi’s.42Jean Trinh, “The Past, Present, and Future of Chinatown’s Changing Culinary Landscape,” February 28, 2017.What this rhetoric of neighborhood revitalization benefiting all does is erase the fact that low-income people are being targeted as obstacles to this revival.4336. Miranda J. Martinez, Power at the Roots: Gentrification, Community Gardens, and the Puerto Ricans of the Lower East Side (United Kingdom: Lexington Books, 2010), 23.

The Chois, Huangs, Changs, and Cailans carry with them social and financial capital that the owners and cooks of many longstanding, family-run, and traditional restaurants, like the recently shuttered J&K Hong Kong Cuisine in Far East Plaza, arguably do not. They garner attention from not only their celebrity and fan following but the support of key players who have disproportionate power in Chinatown such as Yu. Without self-critiquing the financial and social capital that enables them to open shop and exist in Chinatown and without explicitly challenging inequitable development, these businesses are complicit in the neighborhood’s gentrification. Their presence drives further inequitable development and enables the discourse that ignorantly frames Chinatown’s gentrification as “a new commercial renaissance”44Farley Elliot, “Is Majordomo Already Changing Real Estate Fortunes in Far Chinatown?” April 19, 2018. rather than working-class displacement.

The issue at hand is not about Asian American chefs and entrepreneurs opening shop and paving the way for the historically disregarded cuisine of our communities to finally be recognized and valued by the mainstream. It is about the violent displacement of working-class tenants and the equitable future of Chinatown. It is necessary to move beyond the conversation of Asian American representation in haute cuisine so that we can talk about accountability and inequity. With self-critique comes feelings of discomfort and guilt. What tangible actions will follow? How can these restaurateurs — and their supporters — utilize their privilege and power to fight against gentrification? Are they willing to do what they can to demand equitable development, community-driven decision making, and redistribution of capital to the working-class — even if it means calling out BID, developers, and themselves?

Up-And-Coming

Today, Chinatown’s existence as a working-class immigrant neighborhood is often described as fading, dying, or aging, contrasting with a parallel description of it as trending, hip, and revitalizing. In media platforms, it has been referred to as an afterthought, a “hokey, half-dead tourist enclave” that used to have attractive Cantonese cuisine and now has an alluring mix of new and old eateries.45Jonathan Gold, “Chinatown Emerging as LA’s Hottest Restaurant Destination,” January 16, 2015. It has been “sparked into life” by the cheap commercial rents and art gallery boom that spur recent economic development.46Jonathan Gold, “Chinatown Emerging as LA’s Hottest Restaurant Destination,” January 16, 2015. Many of the new wave of restaurateurs, most of whom are Asian American and white, are attracted to “the romance of Chinatown’s history and culture” such as the “raw coolness” of roasted ducks in shop windows.47Eddie Kim, “How an Aging Chinatown Mall Became a Hipster Food Haven,” March 28, 2016. These descriptions are extensions of Orientalist narratives that dehumanize and hypersexualize Chinatown as a dirty, backwards, yet captivating tourist destination. Together they feed into a framing of the neighborhood as something that can then be exploited, conquered, and controlled.

The language that journalists, restaurateurs, and investors use to describe Chinatown can also evoke unsettling references to colonialism.48Some anti-gentrification groups call gentrification the new colonialism. However, this fails to acknowledge settler colonialism and disregards indigenous communities who continue to face the violences of colonialism. Gentrification targets communities already marginalized by the state, but it is a process that is very different from colonialism. See Wakíƞyaƞ Waánataƞ (Matt Remle- Lakota), “Gentrification is NOT the new Colonialism.” Painting cities as “urban wilderness” that needs to be cleaned up and developed, especially by those who are wealthy and white, the language of gentrification incorporates frontier imagery reflective of European colonialism in the Americas.49Neil Smith, New Urban Frontier: Gentrification and the Revanchist City, 1996, xxiii-xiv. Chinatown is seen as both a “fringe neighborhood,”50Eddie Kim, “How an Aging Chinatown Mall Became a Hipster Food Haven,” March 28, 2016. unconventional and “egalitarian,” but holding much potential for economic growth. Jonathan Gold once described the former Starry Kitchen as almost qualifying as a Chinatown “pioneer” in “a brave new culinary world.”51Jonathan Gold, “Chinatown Emerging as LA’s Hottest Restaurant Destination,” January 16, 2015. Roy Choi, who believes Chinatown is a “great area for growth because it’s like an island… you can create your own wonderland over there because it’s all encapsulated”52Jean Trinh, “The Past, Present, and Future of Chinatown’s Changing Culinary Landscape,” February 28, 2017. has been unsurprisingly described with the same terms by peer Eddie Huang. “Roy [Choi] is the pioneer. Roy came opening night, Roy is absolutely the pioneer in Far East Plaza…”53Besha Rodell, “TV Chef Eddie Huang Plans New Outpost of Baohaus in Chinatown,” November 30, 2016. Downtown real estate agencies have taken notice. Derrick Moore, a principal with the commercial real estate services firm Avison Young, calls Far East Plaza a “destination project in the works.”54Eddie Kim, “How an Aging Chinatown Mall Became a Hipster Food Haven,” March 28, 2016.

Disparate Visions

Media coverage of Chinatown is also saturated with discourse that acclaims George Yu as a “visionary.”55Eddie Kim, “How an Aging Chinatown Mall Became a Hipster Food Haven,” March 28, 2016. He is “a leader who genuinely cares about Chinatown,” according to former Pok Pok chef Andy Ricker.7 However, the influx of inequitable development, increased harassment of community members by BID and landlords, and the growing displacement of people and spaces blatantly show how Chinatown as a working-class immigrant neighborhood is not cared for by people like Yu. He, alongside city officials and developers who support neoliberal economic development, work in tandem to sustain an inherently inequitable system. Yet, Yu is presented as “clearly not doing it for the rent money.”56Eddie Kim, “How an Aging Chinatown Mall Became a Hipster Food Haven,” March 28, 2016. Ricker elaborates, “[He] believes that the future of Chinatown is young people coming in and making a stand.”57Eddie Kim, “How an Aging Chinatown Mall Became a Hipster Food Haven,” March 28, 2016. What about the existing population of residents, young and old, who are very much vulnerable to the impact of gentrification today? (Ricker is a celebrated white man who profits from cooking Thai cuisine. He benefits from Yu’s particular vision of Chinatown, despite his two restaurants having closed there a few years prior.)

Yu is not representative of the working-class seniors, families, and tenants who make up Chinatown, despite his staking a claim to knowing what is best. “Because I’ve been here for so long I think I have a good idea of the needs of the community. [The] first priority is still clean and safe, and then all the other good things will follow.”58Jean Trinh, “The Past, Present, and Future of Chinatown’s Changing Culinary Landscape,” February 28, 2017. While issues of habitability and safety can be of real concern in Chinatown, BID’s major role in harassment points to problematic notions of cleanliness and safety that target poor people of color, especially black and brown folks, for removal. Yu fails to prioritize the demands of residents and community members for stable affordable housing, culturally competent healthcare, and relevant businesses.

To envision a Chinatown that is equitable requires centering the working-class and their right to the city — which is “not merely a right of access to what already exists, but a right to change it”5940. David Harvey, “The Right to the City,” 2003, 939. — rather than the desires of the wealthy elite and individuals with disproportionate decision-making power over what happens to the neighborhood. The future of Chinatown as a working-class multiethnic enclave is one that cares for the community’s poor, elderly, people of color, and immigrants. Julie says “我希望唐人街給多點低收入啊. (I hope Chinatown gives more [housing to] low-income people).” Similarly, Pauline hopes for more housing for the large population of seniors that make up 20% of Chinatown (versus LA’s 11%).23 “因為点解咧? (Why?)” Julie asks. “因為呢道很多低收入啊, 嗰啲伯公公婆婆啊, 嗰啲外来人. 佢唔識英文啊. (Because there’s a lot of low-income people, seniors, and immigrants here who don’t know English.)”

She and other seniors continually emphasize that “唐人街很貴租啊! (Chinatown’s rent is very high!)” However, developers continue to propose residential and commercial projects where community needs, such as truly affordable housing, are an afterthought. The government is accountable, because these projects come into fruition when the city’s department of planning expedites6041. Planning and Land Use Management Committee, “Motion: HOUSE LA: Expanding City Planning’s Expedited Processing Section (EPS),” City of Los Angeles Department of City Planning, October 21, 2015. and approves urban planning processes that serve private interests. How can our elected officials claim to fight for the needs of the community when they continue to receive financial contributions from developers? Ultimately, city planning has come to resemble entrepreneurial agents that seek to maximize growth, efficiency and accumulation.6142. Oren Yiftachel, “Theoretical Notes On `Gray Cities’: The Coming of Urban Apartheid?” 2009, 92. When governments prioritize corporations and capital investments (e.g., San Francisco giving tax breaks totalling up to $56 million to the multi-billion dollar tech company Twitter) — rather than working on expanding rent control, investing in public education, addressing homelessness, or improving local employment and wages — they treat cities as places to generate capital rather than places for people to live. We cannot rely on neoliberal state and market processes because they do not ensure equitable control over how neighborhoods are shaped.

Systems and solutions need to be grounded in the political struggles, needs, and visions of working-class communities of color. We cannot let the racism, classism, and patriarchy that manifests as gentrification to thrive in our neighborhoods any longer. Take a clear and unapologetic stance against the forces of gentrification, calling out and holding accountable the Chinatown Business Improvement District, profit-driven developers, and city officials who are complicit in perpetuating this violence. Actively participate in efforts to address root causes of the affordable housing crisis such as the campaign to repeal Costa Hawkins and protect tenants from rents that are just too damn high (#YesonProp10). Critically engage with working-class immigrant residents and community members to ensure the future of Chinatown is one that is both equitable and sustainable. Support the moratorium to fiercely oppose the building of new developments in Chinatown until they meet community demands for historical and cultural preservation and truly affordable housing. And remember, these actions are only the beginning of what you can and should do.

Chinatown’s Future

“希望如果第日唐人街是起啲新屋啊, 新樓啊. 希望他给一啲低收入入住. (If Chinatown builds new housing and new buildings in the future — I hope they let low-income people live there),” Julie emphasizes. “因為咁樣好啲了. (Because — this way things would be better.)”

Frances Huynh is a writer who covers topics on community health, Asian American Studies, storytelling, foodways, and Los Angeles Chinatown.

Learn more about Reappropriate’s guest contributor program and submit your own writing here.