By: Mark Tseng-Putterman (@tsengputterman)

As Asian Americans living in the years of Amy Chua, Ajit Pai, Peter Liang and Nikki Haley, it’s easy to romanticize the Movement: those revolutionary years when “brothers and sisters” from Chinatowns, Little Tokyos, and Manilatowns across the country came together to stand with Black Power and confront the racist war in Vietnam. Together, they made pilgrimage to Manzanar, sat in at Wounded Knee, and walked out at San Francisco State University. Somewhere along the way, they invented “Asian America” as we know it.

As Asian Americans living in the years of Amy Chua, Ajit Pai, Peter Liang and Nikki Haley, it’s easy to romanticize the Movement: those revolutionary years when “brothers and sisters” from Chinatowns, Little Tokyos, and Manilatowns across the country came together to stand with Black Power and confront the racist war in Vietnam. Together, they made pilgrimage to Manzanar, sat in at Wounded Knee, and walked out at San Francisco State University. Somewhere along the way, they invented “Asian America” as we know it.

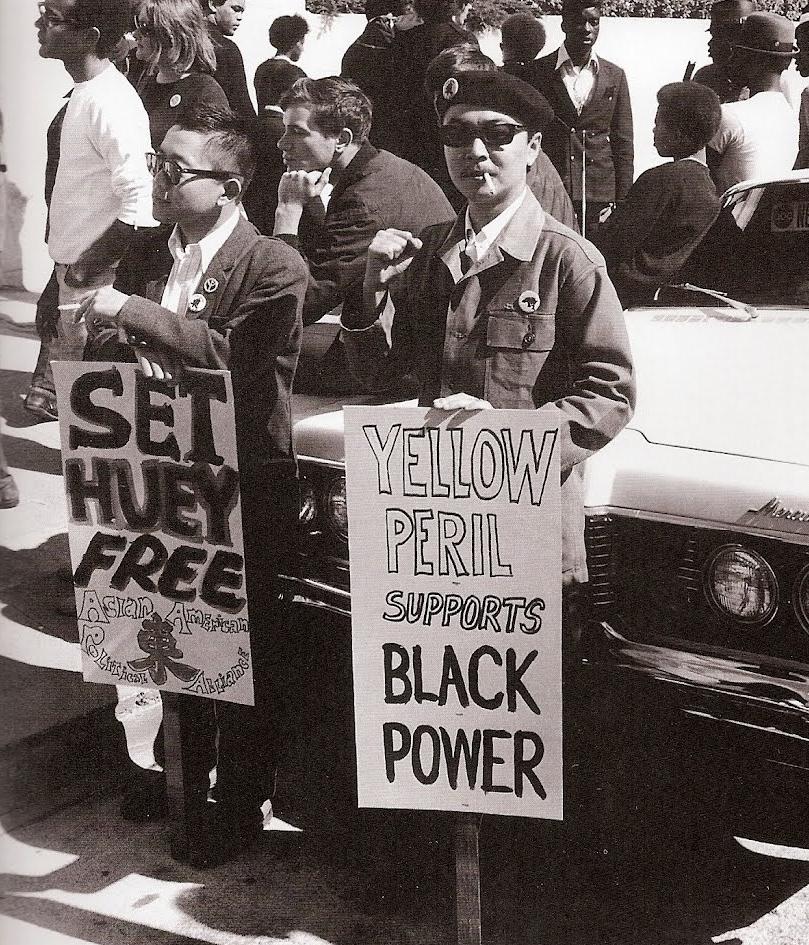

A crash course in the history of the Asian American Movement has become part of the initiation process for young newcomers to the Asian American left, and for good reason. And yet, the images that get circulated from that era—of Black, brown, and yellow brothers wearing leather jackets and berets, fists raised and packing heat—hint at a masculinist underpinning that’s worth unpacking.

Take, for instance, the iconic image of Richard Aoki with Berkeley’s Asian American Political Alliance at a 1968 rally to free Black Panther Party co-founder Huey Newton. Aoki (who in 2012 was implicated as an alleged FBI informant) looks decidedly chic: clad in a black beret and sunglasses with a cigarette protruding from the corner of his mouth, he raises one hand in a fist while the other balances the now-iconic sign: “Yellow Peril Supports Black Power.” But reading this image and its circulation critically, we might ask: Is it Aoki’s revolutionary politics that resonates? Or is Aoki, as a Japanese American man embodying a militant kind of hypermasculinity, rendered iconic for easing modern anxieties about Asian male “emasculation”—that which Tamara Nopper calls “a homophobic and sexist preoccupation among many Asian Americans and our ‘allies’”?

Indeed, while the male leaders of groups like the Black Panthers, the Young Lords, and I Wor Kuen waged war on police violence, capitalist exploitation, and American imperialism, the women in their ranks were fighting their own battle against “male chauvinism”—what we might call toxic masculinity in today’s parlance—in the Movement.

The early Panthers, like many revolutionary men of color, saw racism as a castrating force that could be resisted by reclaiming a normative kind of hypermasculinity. As historian Tracye Matthews argues, the early Black Panther Party “[linked] Black liberation to the regaining of ‘Black manhood’,” a philosophy that was challenged by rising Black women leaders like Elaine Browne, Audrea Jones, and Assata Shakur. These women courageously pushed the Party’s gender politics away from a conservative masculinism that was often both misogynistic and homophobic. Instead, women in the Party pushed male leaders such as Eldridge Cleaver and Huey Newton to call on their fellow brothers to confront male chauvinism within their ranks—an obligation Cleaver called “mandatory” in a 1969 statement in support of incarcerated Panther leader Ericka Huggins. Yet, these evolving gender politics are too often erased in popular depictions of the Party, in favor of what Matthews calls “romanticized, flat images of angry, hard bodies with guns.”

That same romantic masculinism risks erasing the importance of feminist politics in the Asian American Movement. While male leaders of Asian American groups like I Wor Kuen, the Red Guard, and Wei Min She emulated the Black Panther’s early aesthetic of militarized masculinity, Asian American women in the Movement were often relegated to the role of secretary or sex object. In Serve the People: Making Asian America in the Long Sixties, Karen Ishizuka recounts Movement activist Steve Louie’s slow realization of the maleness and misogyny in the Movement:

At one [anti-war newspaper] meeting, one of the women typists—“and that’s what I thought of her as, one of the women typists”—addressed the male leadership in a rage of frustration. “You assholes aren’t listening to us and we’re changing the way this organization works now….We know how to put the paper out, you don’t.”

The moment was a wakeup call for Louie, who had been oblivious to the marginalization of women in the Movement. He later reflected: “If you’re going to put women down, you’re cutting out half the sky and most of the room….you better figure out what your blinders are. At that time I realized I had blinders on, and I didn’t even know it.”

As Louie’s anecdote demonstrates, men of color are admittedly slow—or worse, defensive—about grasping the extent of misogyny and male supremacy in otherwise anti-oppressive spaces. To many, the prevalence of sexism and patriarchy amidst the rhetoric of revolutionary equality represented a fundamental Movement contradiction. As Evelyn Yoshimura put it: “Eventually it became clear that even within the Movement, where we were talking about creating a different kind of society…there were problems with women not being taken seriously, or their work not being looked at in the same light.”

A January 1971 issue of the Los Angeles-based Asian American newspaper Gidra was a clarion call regarding the barriers facing Asian American women in the Movement. The issue called Movement brothers to confront their own sexism — biases they argued reflected the oppressive power structures the Movement sought to tear down. Meanwhile, contributors insisted on analyzing gender as a central axis of oppression alongside race and class: Evelyn Yoshimura connected anti-Asian misogyny to U.S. militarism, highlighting the stereotypes that white American GIs stationed in Asia were bringing back to the United States. Others, like Yvonne Wong Nishio, critiqued the invisibilization of Asian American women’s contributions to Movement work. Nishio wrote: “Little recognition is given to women who actually do the work. Can you remember who did the typing, who ran the office machines, who did the telephoning, and who did the tedious research?”

Despite the constant threat of being labelled “race traitors” or sellouts for articulating an Asian American feminist praxis, the women of Gidra didn’t shy away from implicating the male egos of their “brothers” that created a climate of misogyny in the Movement. As Wilma Chen wrote in “Movement Contradiction”:

There is a group of primarily Asian-American males who feel that they have been so ‘emasculated’ by white racism that they cannot stand to see women in roles of equality or leadership in the movement. These men fail to realize that the white stereotype of the Asian women as sleek and sexy Susie Wong is just as dehumanizing to Asian women as the bucktoothed laundry man stereotype is to Asian men….it is racism and not Asian women that have ‘emasculated’ Asian men. ‘Emasculation’ becomes a rationalization for weakness and an excuse not to struggle against sexism.

It’s a sad reflection of the durability of misogyny in our communities that Chen’s words feel just as relevant almost fifty years later. Today, a subgroup of Asian American men continue to insist that Asian American women wield power and privilege over them by virtue of their fetishization.

Such a claim is only possible if one disregards the core analytical frameworks of the Asian American Movement: anti-imperialism and class struggle. Citing the gender wage gap and the expectation of women to perform uncompensated domestic labor, Yvonne Wong Nishio wrote in Gidra that men “reflect the capitalist society which we reject” by devaluing women’s work in the Movement. Linda Iwataki referenced Mao Tse-Tung’s declaration that women are dominated not only by political, clan, and religious authority, but also the “feudal-patriarchal ideology and system,” arguing that male chauvinism “is a manifestation of the values of an exploitative system and that these are the same values held by the ‘ruling class’ which exploits and oppresses [men].” Recognizing the intersecting forces of racism, capitalism, and sexism, Asian American women in the Movement mobilized to organize Asian immigrant garment workers in New York City and Los Angeles into the 1980’s.

Meanwhile, the dehumanization of Asian and Asian American women was consistently linked back to the racist war in Vietnam and U.S. imperialism in Asia writ large, with figures such as the women leaders of the Vietnamese National Liberation Front heralded as early Asian/American feminist icons. Iconic depictions of a North Vietnamese woman clutching a rifle in one arm and a nursing infant in the other put a feminist twist on the Movement’s militant imagery.

Alongside their Black, Chicana, and Native sisters in struggle, Asian American women in the Movement advanced a feminist of color critique that forced male activists to recognize that ending male chauvinism was inseparable from their struggles against imperialism and capitalism. By 1969, I Wor Kuen’s 12-point program proclaimed: “We want an end to male chauvinism and sexual exploitation,” citing “thousands of years of oppression under feudalism and capitalism [that] have created institutions and myths of male supremacy over women.” Meanwhile, the Young Lords (a revolutionary Puerto Rican group) declared in their party platform: “under capitalism, our women have been oppressed by both the society and our own men.” In parallel, grassroots women’s groups such as the Asian Women’s Center and Asian Sisters grew out of the Movement, forming drug support groups for Asian American women, providing childcare services for Chinatown workers and Movement activists, and organizing women’s health clinics for working-class women in the community.

Fifty years after Huey Newton implicated heterosexual male insecurities for homophobic and sexist aggression (“we want to hit the women or shut her up because we are afraid that she might castrate us, or take the nuts that we might not have to start with”), the obligation of men of color to confront male chauvinism in activist spaces remains, as Eldridge Cleaver put it, mandatory. From the unrecognized emotional labor of women and gender minorities in community organizing, to the prevalence of sexual assault in activist spaces, to the internet firestorms over Asian American female “privilege,” male chauvinism continues to loom large in supposedly radical and progressive spaces. Asian American men who claim to be invested in anti-oppression do a disservice to the Movement when they cling to its militant masculinist aesthetic while erasing the contributions and struggles of the women within it. To claim the romantic imagery of brothers clutching rifles and picket signs but to ignore or reject their grappling with oppressive masculinity is to reject the sum of their revolutionary legacy.

It is time to recommit ourselves to I Wor Kuen’s call: “we want an end to male chauvinism.”

Further reading:

- The full run of Gidra is available online through Densho’s digital repository.

- Laura Pulido, “Patriarchy and Revolution: Gender Relations in the Third World Left” in Black, Brown, Yellow and Left: Radical Activism in Los Angeles.

- Karen Ishizuka, Serve the People: Making Asian America in the Long Sixties.

- Haruka Sano, “How did the staff of Gidra, a newspaper started in 1969 by Asian American students at University of California, Los Angeles, successfully and unsuccessfully advocated (sic) for Asian American women?”

- Jaeah J. Lee, “The Forgotten Zine of 1960s Asian-American Radicals,” Topic.

- “Black Panther Sisters talk about Women’s Liberation,” The Movement, 1969.

Mark Tseng-Putterman (@tsengputterman) is a writer and scholar focusing on Asian American social movements, coalition politics, and race and digital media.

Write Back, Fight Back(#WriteBackFightBack) is a weekly essay series sponsored by 18MillionRising, Asian Americans Advancing Justice, and Reappropriate. It features emerging Asian American writers on topics of racial and social justice. New essays will appear every Thursday.