By: Frances Kai-Hwa Wang (@fkwang)

The night before my youngest child – whom we call Little Brother – leaves on a four-day eighth-grade field trip to Washington D.C., I double-check his suitcase against the school’s packing list to make sure he has everything he needs. He has packed too many shirts and pants, and not enough socks and underwear. He forgot deodorant, a critical item for eighth-grade boys. The long-sleeved green school t-shirts that the students will wear at all times during the trip are in the dryer. The batteries for his camera and phone are charging in the kitchen. I tuck a box of musubi into his day pack as a snack for the bus. I remind him to brush his teeth every day and to text me every night.

The night before my youngest child – whom we call Little Brother – leaves on a four-day eighth-grade field trip to Washington D.C., I double-check his suitcase against the school’s packing list to make sure he has everything he needs. He has packed too many shirts and pants, and not enough socks and underwear. He forgot deodorant, a critical item for eighth-grade boys. The long-sleeved green school t-shirts that the students will wear at all times during the trip are in the dryer. The batteries for his camera and phone are charging in the kitchen. I tuck a box of musubi into his day pack as a snack for the bus. I remind him to brush his teeth every day and to text me every night.

Then I tell him what to do in case of a mass shooting.

Stay calm. Barricade the door. Duck behind furniture. Keep moving. Get out. Just get out.

Little Brother is thirteen years old.

And then, so that he does not worry, I lie to my son.

I tell him that since the president will be out of the country the week of his trip, Washington will probably be quieter while he is there.

I do not know if that is actually true. But, I do know that even if he were here, at home, he would not be any safer. Any of us could be caught in a mass shooting or a random act of violence anytime, anywhere.

The day that Little Brother leaves for his big field trip happens to be Election Day. Schools in our city are closed because many polling places are in schools, and our state allows open carry of guns in schools.

On that same day, our state legislature votes to “fix” the open carry law by amending it to allow for concealed carry of guns in schools, hospitals, churches, and day care centers. The legislators in favor of the amendment say that people will not become more fearful when they see people open carrying guns in these public places. Seriously?

I’m already scared.

* * *

I started writing this essay last November, one month after the shooting in Las Vegas and one week before the shooting at Rancho Tehama Elementary School in northern California. But I never submitted it because by the time I was done, I did not think that speaking out again would make any difference. Moreover, I was not in the mood to be attacked by angry “gun people”.

Later, I receive an offer from my life insurance company to double the payout of my life insurance policy in case of accidental death. I calculate the additional cost and wonder about the odds that I will be shot to death before I turn 68 (when my life insurance coverage ends).

I just want my children to be safe.

* * *

When George Zimmerman was acquitted for second degree murder and manslaughter in the shooting death of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin in 2013, Little Brother was nine years old. My son was tall for his age, and beautifully brown from the summer sun. Looking at him, I suddenly realized that although all the aunties coo over him – “xiao shuai ge” (little handsome brother), they say – not everyone will see him as the sweet and kind boy that I know. Because he is multiracial, Little Brother can look like any number of racial stereotypes.

And, he loves hoodies.

I began to coach Little Brother on how to take his hoodie off; how to control his voice and volume even if angry or afraid; how to talk to police and strangers respectfully; how to move slowly and to keep his hands visible; how to look out for himself and his friends. Then, after he panicked when he saw two police officers at the grocery store, I also try to teach him how to not be afraid of the police when he really needs them, and how to tell which strangers would be safe to ask for help when needed.

Does any of this really help? I don’t know.

Instead, I am told that what we need is more good guys with guns, or even teachers with guns.

* * *

Those who carry guns often think that they are the ‘good guys’ – and, indeed, they might be. But, I’m not so naïve. I know that they could just as easily not be good guys. Or, they could be good guys having a bad day. Or, they could be good guys who mistake me and my family and our friends for bad guys. Or, they could even be bad guys who simply have not yet acted on some violent impulses, or who have done so and have not yet been caught.

Or, maybe the world isn’t so easily divided into good guys and bad guys. I mean, there are priests who do bad things, and there are toddlers who accidentally shoot people.

I cannot simply place my trust in people when so much of the history of white supremacy has been invested in casting people who look like me, my family, and my community as the ‘bad guy’, and not supporting us when we are not. The view is different here from the POC seats.

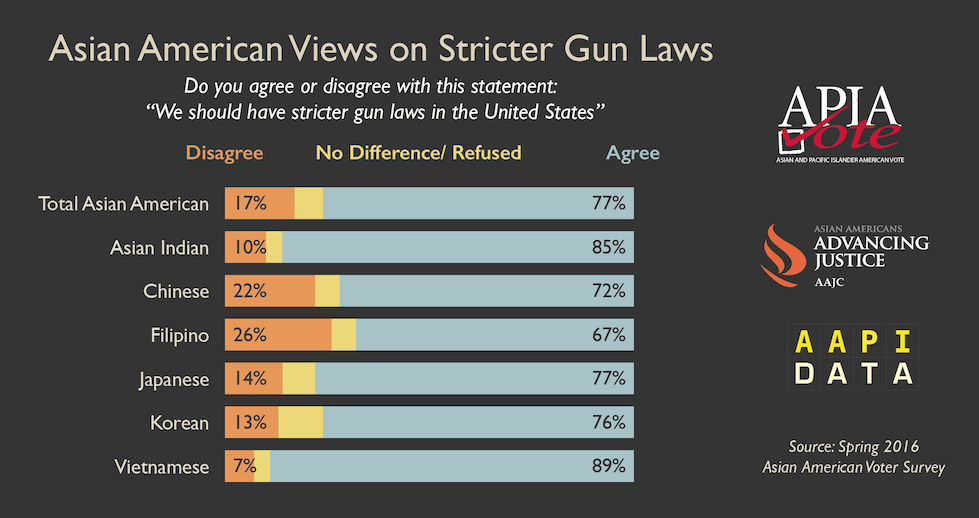

According to AAPI Data, 77 percent of Asian Americans support stricter gun laws. When the data is disaggregated by ethnicity, support can run as high as 89 percent among Vietnamese Americans and 85 percent among Indian Americans. Not that it seems to matter.

Although we are not always included in the national narrative, Asian Americans see gun violence as very much an Asian American issue. We are both victim and, occasionally, shooter. We are both targeted for and shaped by the perceptions that we are different, foreign, immigrant, terrorist, and other. Yet, whether a crime is prosecuted as a hate crime seems almost as random.

Some high-profile mass shootings targeting Asian Americans include: the 1989 school shooting at Cleveland Elementary School in Stockton, California, in which five Southeast Asian American children were killed, and 29 students and one teacher were injured, which became the impetus for the California state and federal assault weapons bans; the 1999 Los Angeles Jewish Community Center shooting, which was followed by the shooting death of Filipino-American U.S. postal carrier Joseph Ileto; the 2012 shooting at the Sikh Gurdwara in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, killing six people and wounding four more; the 2014 Isla Vista killings near the campus of University of California, Santa Barbara, which began with the stabbing deaths of the alleged gunman’s three Chinese-American roommates; the 2016 Wisconsin shooting deaths of Mai and Phia Vue and Jesus Manso-Perez in their own homes by a neighbor; the 2017 Kansas shooting death of aviation engineer Srinivas Kuchibhotla which left two others injured by a man shouting, “Get out of my country.”

After any shooting, I hold my breath to see how the shooter is described: terrorist or deranged loner – in other words, Muslim/Arab/Asian/POC/other or white. The 1989 Stockton school shooting and the 1999 LA Jewish Community Center and Joseph Ileto shooting were both called ‘terrorism,’ however since September 11, 2001, white people with terrorist agendas are no longer called terrorists. Today, the immediate labeling of Muslim/Arab/Asian/POC/other shooters as ‘terrorists’ does not really tell me anything, and the way that white shooters are treated so much more carefully than shooters (or Good Samaritans) of color does not engender confidence. And so we find ourselves feeling exposed at school, at cultural centers, at work, at temple, at university, in our own homes, and in public places. And heaven help us if we have mental health issues and need help.

* * *

After the recent shooting in Florida and the amazing vocal mobilization of the high school students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School – where seventeen students and teachers were killed and sixteen more were injured – I am surprised and hopeful to see that things might finally, slowly, be starting to shift.

It has been six years since the shooting death of Trayvon Martin, also in Florida. There have been so many shooting deaths and so much youth and community organizing since then, including the good work of the Dream Defenders, Black Lives Matter, #FlintKids, #Asians4BlackLives, the Women’s March, and #MeToo. And now #Enough and #NeverAgain are finally being heard.

During this time, I have seen Chinese American grandmas in their big floppy hats marching in protest of the Muslim Ban. I have seen Japanese American children protesting the racism of Dr. Seuss at their elementary school. I have seen Sikh Captain America engaging people one at a time outside of the Republican National Convention. I have seen a multiethnic and multilingual group of Asian Americans put their years of language school to use to draft a letter in 32 languages to explain the importance of Black Lives Matter to their elders. And every year on the anniversary of the shooting in Oak Creek, the Sikh American community hosts a fun run and blood drive in Oak Creek, and Sikh Americans across the country volunteer for a day of community service.

I always show Little Brother these images and tell him these stories in the hope that he will hear possibility and inspiration, and not just fear.

Today, Little Brother comes home from school to tell me that he and his friends are planning a school-wide walkout on March 14 in connection with the national walkout to commemorate the victims from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, and to call for an end to gun violence.

His group has been meeting with the principal to plan so that people do not goof off, or run away, or make trouble during the seventeen minutes of the planned walkout. He is also spearheading a special issue of the school paper to focus on the issue of guns and school.

A week ago, Little Brother was worried about being the only one to protest, or of not having enough time to get to his locker before his next class, or of getting in trouble with his teachers.

Today, he is an organizer.

Frances Kai-Hwa Wang is a journalist, essayist, speaker, educator, and poet focused on issues of diversity, race, culture, and the arts. The child of immigrants, she was born in Los Angeles, raised in Silicon Valley, and now divides her time between Michigan and the Big Island of Hawai‘i. She has worked in philosophy, ethnic new media, anthropology, international development, nonprofits, and small business start-ups. Her writing has appeared at NBC News Asian America, PRI Global Nation, New America Media, Pacific Citizen, Angry Asian Man, Cha Asian Literary Journal, Kartika Review, and several anthologies, journals, and art exhibitions. She teaches courses on Asian/Pacific Islander American media and civil rights law at the University of Michigan, and she teaches creative writing at University of Hawaii Hilo and Washtenaw Community College. She co-created a multimedia artwork for the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center Indian American Heritage Project online and travelling art exhibition.

Write Back, Fight Back (#WriteBackFightBack) is a weekly essay series sponsored by 18MillionRising, Asian Americans Advancing Justice, and Reappropriate. It features emerging Asian American writers on topics of racial and social justice. New essays will appear every Thursday.