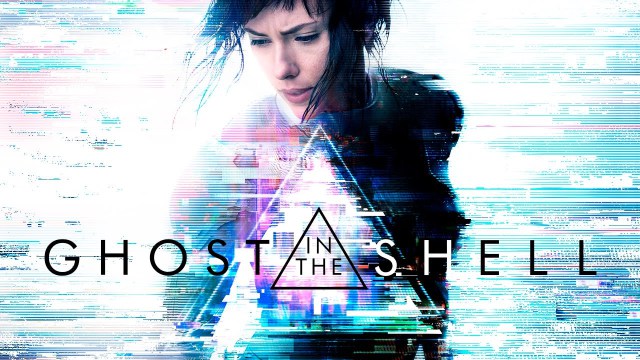

This weekend, Hollywood’s live-action remake of the classic Ghost in the Shell anime opened in theatres nationwide. The film has been the subject of intense scrutiny including charges of White-washing related to the filmmakers’ highly-questionable decision to cast Scarlett Johansson in the leading role of Major Motoko Kusanagi. (In the Hollywood remake, the character is renamed Major Mira Killian to suit Johansson’s clearly non-Japanese appearance.)

Ghost in the Shell (2017) deserves all the harsh criticism it has received from movie critics and the Asian American community. Supporters of the film object, saying that the White-washing debate is a distraction. In fact, the White-washing controversy is totally relevant; moreover, it is symptomatic of the film’s essential problem: Ghost in the Shell (2017) fundamentally misunderstands its source material.

Whether due to ignorance or apathy, Ghost in the Shell (2017) fails to recognize the key thematic elements of the 1995 anime — Ghost in the Shell (1995) — from which it derives its inspiration. While Ghost in the Shell (2017) faithfully recreates many of Ghost in the Shell (1995)‘s most iconic scenes in breathtaking live-action CGI, Ghost in the Shell (2017) lacks any of Ghost in the Shell (1995)’s philosophical or theological essence. What results is an awful, wooden, lacklustre, and overtly racist live-action remake: a stilted, soulless artifice wrapped in the visually stunning iconography of the Ghost in the Shell anime franchise.

In other words, Ghost in the Shell (2017) is a shell without a ghost. All the good things about Ghost in the Shell (2017) come from the original anime, and all the terrible things are both uninspired and racist.

This review contains spoilers of both Ghost in the Shell (2017) and Ghost in the Shell (1995), as well as a brief spoiler of Ex Machina (2014). Please read on with care.

The Themes of Ghost in the Shell (1995) and How Ghost in the Shell (2017) Got It All So Wrong

It wouldn’t be much of an understatement to say that I grew up on the Ghost in the Shell anime franchise.

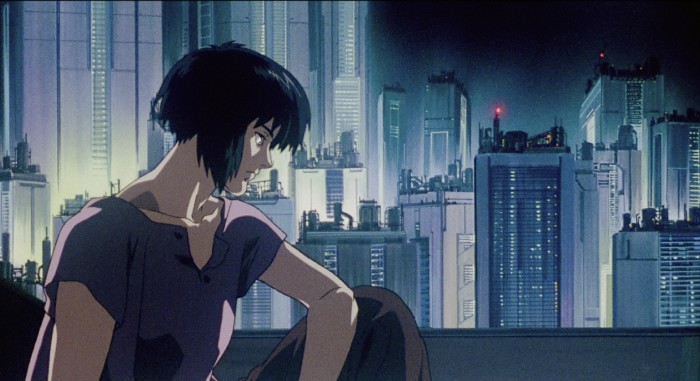

For much of my childhood, I believed that the kid-friendly focus and overly-simplistic themes characteristic of the Disney films I grew up on were an innate limitation of the hand-drawn animation genre. And then, on a whim, I rented the Ghost in the Shell (1995) animated film by director Mamoru Oshii — enticed more by the art of the VHS box cover than by anything else. From the first haunting chants of the film’s opening sequence interweaved over stunning visuals of a cybernetic body receiving layers of synthetic muscle, sinew, and skin and so appearing progressively more human, I was instantly hooked. These two minutes captured the essence of the subsequent film’s central questions: What is it that defines our existence and our individuality? What makes us who we are and whom we will become?

For a nerdy fourteen-year-old Asian American girl still struggling with her own coming-of-age story, this question could not have been more relevant. Over the years, I found myself returning often to Ghost in the Shell, examining and re-examining the film’s core philosophy, spirituality, and theology. With each new viewing, I discovered a fresh facet of the film to mull over. Later, both my husband and I went on to watch every film and episode installation of the Ghost in the Shell animated universe.

Ghost in the Shell stirred in me a realization that art and film can and should be so much more than mindless escapism. It should challenge the mind, provoke the soul, and question our most deeply held beliefs. Truly visionary art is not easy, saccharine, and forgettable; instead, it pushes the boundaries of its own genre with (sometimes uncomfortable) complexity that stays with the viewer long after the end credits have rolled. Indeed, it is the 1995 anime’s deft exploration of sophisticated existentialist concepts and questions — and not just its most iconic visuals — that cemented Ghost in the Shell (1995)‘s status as a revolutionary instant-classic, having since inspired numerous science fiction epics such as The Matrix, Avatar, and A.I.: Artificial Intelligence and countless more.

Ghost in the Shell‘s core mythos asserts that all individuals consist of both shell (a physical form, including a software- and hardware-augmented cyberbrain) and ghost, a loosely-defined term that refers to the ego constructed out of each individual’s sentience, will, spirituality, memory, agency, instinct and intellect. Robots, even those of high artificial intelligence who are otherwise capable of mimicking human behaviour, lack a ghost whereas even the most cyberized of cyborgs possess one. Thus the quest to understand and explore that which defines and shapes one’s ghost forms the thematic backdrop of Ghost in the Shell‘s philosophical ruminations. Within this framework, Major Motoko Kusanagi’s character serves as a central reference point: unlike the other cyborgs of Section 9, the Major was fully cyberized at birth after her pregnant mother was killed in an accident. Thus, unlike other cyborgs, the Major lacks any memory of life before cyberization. And yet, her ghost echoes strongly within her shell: she is unyieldingly certain of her own humanity and individuality, and seeks to evolve beyond her own cybernetic existence.

The strength of Major Motoko Kusanagi’s assurance in her own ghost is central to Ghost in the Shell. Her confidence drives the viewer’s own understanding of what a ghost is and how it is an essential component of human individuality. Motoko is steadfast in her knowledge that she is an individual, and that this individual is a cyberized, Japanese woman and a member of Section 9 who is much more than the sum of her cybernetic parts. Indeed, her clear drive to evolve beyond the confines of her own cyberization is a defining element of her strong personality, and has lead many to characterize Major Motoko Kusanagi as an early Asian feminist pop culture icon. When first introduced in Ghost in the Shell: Arise, Motoko is mired in a legal fight with the Japanese military to establish that despite her fully-cyberized body, she is not military property and deserves personal and financial autonomy. After winning her freedom, the Major joins Section 9 where her strong ghost allows her to be a wizard-level hacker, capable of diving into other people’s cyberbrains and even temporarily take hold of their cyborg bodies without losing her own identity and sense of self.

The writers excise other key details of Ghost in the Shell (1995) that help establish the philosophical tension between ghost and shell. Rather than to depict the future as a world where cybernetic enhancements are culturally accepted and where cyborgs are integrated members of society, Ghost in the Shell (2017) instead opts for a world where cyberization is cutting-edge, and where no person has been fully cyberized save the Major. Batou, Borma, Ishikawa, Saito — all full cyborgs in the anime — are portrayed as partially-cyberized Frankensteins, who replace essential organs as they are damaged but who are otherwise largely human. Togusa — a quintessential character in the anime who embodies stereotypical characteristics of humanity as reference for the rest of Section 9’s full cyborgs — is reduced to the role of background extra. In contrast to the character’s crucial thematic role in the anime, Togusa appears only briefly, and his eschewment of cyberization is referenced without context and as mere afterthought. Batou’s mid-story acquisition of his sleepless eyes — which he chooses for their function in helping to enhance his performance in the field — are presented as transforming him into more machine than man.

In other words, ghosts — the concept that made Ghost in the Shell (1995) genre-redefining — go largely unexplored in the Ghost in the Shell (2017) film. Instead, humanity and individuality in Ghost in the Shell (2017) is linked primarily to each character’s balance of organic vs. non-organic body parts — an idea that is as stale as it is overly-simplistic. Absent the anime’s visionary philosophy and theology about ghosts and shells, Ghost in the Shell (2017) offers nothing substantive or revolutionary as substitute. And so, this live-action movie is entirely diminished by Hollywood filmmakers’ failure to understand and translate that which made the original anime iconic: unlike its revolutionary inspiration, the 2017 remake is little more than a series of uninteresting and uninspired science fiction cliches wrapped in pretty packaging.

There are some who misinterpret Ghost in the Shell‘s cybernetic technology culture as evidence of a post-racial utopia. They argue that in a world where cyborgs can exchange bodies at whim, and where ghosts exist in an interconnected online net where avatars might take on any appearance, identities linked to physical appearance such as race and nationality would be meaningless. These detractors argue that although Major Motoko Kusanagi appears Japanese, she has no true race or ethnicity. Thus, they further argue, Scarlett Johansson’s casting is not White-washing because Motoko Kusanagi wasn’t really Asian to begin with.

These folks miss the ample evidence within the Ghost in the Shell animated series that suggest that not only are ghost and shell conceptually linked, but that race and ethnicity are key components of self-identity for unenhanced humans and cyborgs alike.

The Ghost in the Shell animated franchise is set in a futuristic Japanese metropolis where race and ethnicity remain key aspects of local and global politics. Section 9’s members view themselves as both ethnically and racially Japanese people and loyal actors of the Japanese state who must navigate an intricate geopolitical landscape. A primary issue for Section 9 are ethnic minority refugees of countries invaded by Japan in an earlier unseen war, including those who seek entry into Japan and who have been ghettoized into low-income slums, as well as those who have become terrorists against the Japanese government. Race and ethnicity are therefore not invisible concepts in the Ghost in the Shell world; rather, ethnic tensions rise frequently to the fore. In Ghost in the Shell: Arise (Border 2), Togusa — who is still a police detective in a local precinct — interviews a person of interest in the suspicious death of a fellow police officer. He opens the interview by noting that his suspect is a member of the Kardi ethnic minority, which leads him to question where her loyalties lie. Later stories in both Ghost in the Shell: Arise and Ghost in the Shell: Stand-Alone Complex continue to establish that the race and ethnicity of Japanese and non-Japanese people is a defining aspect of the political landscape in which Ghost in the Shell‘s Japan finds itself.

The facts from the Ghost in the Shell source material are incontrovertible: Major Motoko Kusanagi is an East Asian (Japanese) woman who views herself as such, and who further reflects these identities in both her ghost and her shell. Any casting of a White actor to play her character is therefore obvious and blatant White-washing of an Asian female character.

In early press appearances for Ghost in the Shell (2017), Scarlett Johansson deflected charges of White-washing by insisting that she was not playing a Japanese character in the film. She famously told Marie Claire:

“I certainly would never presume to play another race of a person. Diversity is important in Hollywood, and I would never want to feel like I was playing a character that was offensive.”

We now know this statement to be a bold-faced lie. A surprising-but-not-surprising plot twist in Ghost in the Shell (2017) is the revelation that Major Mira Killian is actually an anti-cyberization activist named Motoko Kusanagi whose entire collective of teenaged Japanese street kids was kidnapped by Hanka Robotics to serve as brain donors for the company’s full cyberization experiments.

This plot twist renders Ghost in the Shell (2017) a particularly overt example of racist Hollywood White-washing. In other films like Dragonball, The Last Airbender, and Dr. Strange, originally Asian characters were either rewritten as White or simply presented bearing White faces with no additional narrative commentary. Not so in Ghost in the Shell (2017). In this movie, not only is Major Mira Killian literally a young Japanese woman being played by a White female actor, but Michael Pitt’s Kuze is also literally a young Japanese man being played by a White male actor.

I’ll confess, I predicted this “plot twist” from the outset. After all, Hollywood is about half as clever and about twice as racist as they believe themselves to be. Still, the third act of Ghost in the Shell (2017) remained deeply uncomfortable to watch as an Asian American female moviegoer.

In 2014’s Ex Machina, a conniving White female android peels the synthetic skin from a dead East Asian robot’s body and wears it to mask her own metal form so that she may make the final steps of her journey towards freedom. Some heralded the film as feminist parable, but in this scene all I saw was the figurative rape of an Asian female form alongside the film’s earlier depictions of violence against other women of colour.

In both Ex Machina and Ghost in the Shell (2017), Asian women are rendered entirely mute as our bodies are repurposed for the empowerment of White womanhood. In Ghost in the Shell (2017) this plot device is particularly gruesome: Motoko Kusanagi (who bears the name of one of the most powerful and self-confident Asian female characters in science fiction pop culture) is silently and senselessly destroyed, her brain is harvested, and her identity is utterly erased — all in service of Major Mira Killian’s personal advancement.

In this context, the film’s live-action recreation of Ghost in the Shell (1995)‘s iconic shelling opening credits — presented in the anime as a hauntingly beautiful scene of birth and life — takes on a darker metatext: in Ghost in the Shell (2017), the shelling sequence becomes a disturbing celebration of the figurative rape and violent destruction of an Asian woman’s body, mind, and spirit in service of White female liberation.

(Even while the film’s final plot twist turns the notch up on the White-washed racism of Ghost in the Shell (2017), the film stubbornly refuses to address questions of race that necessarily emerge from this writing. Neither Kuze nor the Major experience the trauma of their cyberized transracialization. Dr. Oulet does not explain why she creates White-passing bodies for her Japanese cyberization subjects, nor is she held accountable for these decisions. Motoko Kusanagi’s identity and individuality is discarded as quickly as it is discovered.)

Paralleling Motoko Kusangai’s treatment in the film is Ghost in the Shell (2017)‘s crass use of the Geisha-bot character. In the film’s opening action scene, the unspeaking Geisha-bot — having earlier been hacked by Kuze — attacks a high-ranking Hanka Robotics executive, and is shot by the Major as symbolic rejection of her own cyberization. The shattered form of the Geisha-bot — which bears the computer-generated face of Japanese actor Rila Fukushima — reappears to progress both the film’s plot and the Major’s own character evolution. Here again the broken silent corpse of an Asian woman is used as plot device in service of a White female protagonist.

Indeed, the entirety of Ghost in the Shell (2017) can be seen through this lens: Asian cyberpunk aesthetics and faceless Asian/Asian American actor-extras are combined into an Orientalist mishmash of a shell wrapped around an empty and hollow story about White womanhood.

If there ever was a movie about how White feminism thoughtlessly commits violent erasure of Asian American feminism, this would be it.

Ghost in the Shell (2017) Is Not Worth Your Time or Money, but the Ghost in the Shell Anime Series Totally Is

A recurring image in Ghost in the Shell (2017) is that of a burning Shinto shrine. I find this apt: Ghost in the Shell (2017) is a stinking, racist tire-fire feeding upon the charred remains of a beautiful and wonderful, classic Japanese anime. The only redeemable aspects of Ghost in the Shell (2017) are its remade scenes from Ghost in the Shell (1995) and plot ideas taken from Ghost in the Shell: Arise and Ghost in the Shell: Stand-Alone Complex. No surprise, then, that the film is a giant flop: in its opening weekend, Ghost in the Shell (2017) grossed a pitiful $19 million dollars — less than one-fifth its $110 million production budget.

I have only one hope: that from all of this there will be resurgent interest in the original Ghost in the Shell anime series. To that end, I urge you not to spend your money on Ghost in the Shell (2017). Instead, go rent the Ghost in the Shell series and prepare to have your mind blown. The anime is well worth your time and money; the racist, steaming pile of horse-shit playing in theatres right now most certainly is not. That piece of shit that Hollywood made doesn’t deserve to bear the name “Ghost in the Shell”.