This year marks the 70th year of the closing of the World War II incarceration camps (JACL’s “Power of Words”) that imprisoned thousands of Japanese American civilians under inhumane conditions and threat of violence. Yet, this shameful and racist episode of American history still receives scant attention in our history classrooms. The vast majority of Americans know that our government incarcerated Japanese American families behind barbed wire fences, but know precious little else about it.

Yet, Japanese American incarceration is of particular relevance given today’s political climate. The growing global presence of fundamentalist terrorists – who falsely justify their violence with appropriated references to the Islamic faith, yet who just last week took the lives of hundreds of innocent Muslims and non-Muslims in various parts of the world — has lead to intense Islamophobia. Our world once again stands at a precipice: we find ourselves once more ready to commit the unforgivable sin of failing to distinguish between our enemy’s heinous violence, and their race or faith. We again find ourselves in danger of persecuting our innocent neighbours as an expression of our grief-turned-unforgivably-racist-rage. Already, our politicians suggest with possible sincerity that we round up American Muslims and house them in camps – “for our own protection”.

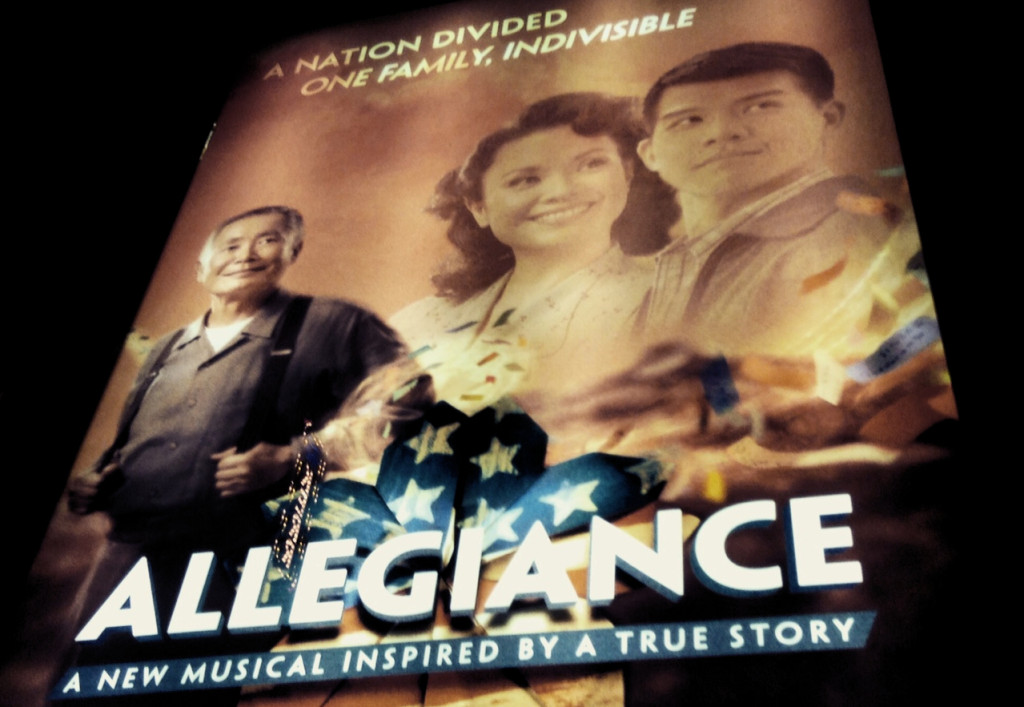

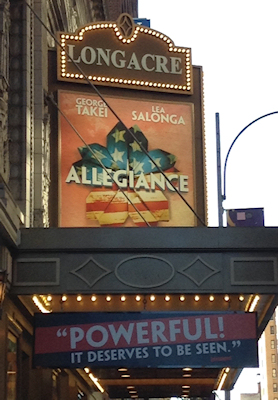

“Allegiance” — a musical written by Jay Kuo and inspired by the experiences of former Tule Lake incarceree, famed Star Trek actor, and vocal Japanese American community advocate George Takei – opened this month on Broadway in New York City; it had previously opened in San Diego in 2012. “Allegiance” challenges us to learn about the camps not as artifacts of history, but through the lens of the lives torn asunder by them; and for this specific moment in the global War on Terror, this story seems particularly poignant and timely.

For many of us in the Asian American community, Japanese American history is a familiar subject. My most striking learning moment with regard to incarceration was when I experienced a recreated shack at the Smithsonian. But, these experiences – while haunting – are largely static. We can imagine the ghosts of those who endured camp life (many of whom have since passed), but in these exhibits, we cannot see them. “Allegiance” brings those ghosts back to life. Several scenes rendered the heartache and heartbreak of this period in Japanese American history with such depth that I found myself deeply moved. One wordless scene which references Hiroshima and Nagasaki was a particularly powerful and evocative tribute to the emotional trauma that is otherwise typically divorced from our teaching of this unforgivable moment in global history. In far less overt form, this – the addition of a lived experience to our teaching of incarceration — is also the larger purpose of “Allegiance’s” retelling of Japanese American history.

“Allegiance” explores the impact of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066 – which led to the forced incarceration of over a hundred thousand Japanese Americans living on the West Coast – on the Kimura family. The Kimura family includes composite characters inspired by Takei’s own childhood at Tule Lake, and documents their life in Heart Mountain.

The musical deserves unconditional praise for how it tackles a complicated episode in Japanese American history by demonstrating how incarceration literally and figuratively tore apart individual families and the larger community. “Allegiance” presents vastly differing responses to life in the camps that accurately reference the real, conflicting reactions that emerged out of the Japanese American community at the time; each is treated with complexity, humanity and nuance. Sammy Kimura (played by Glee alum, Telly Leung) feels compelled to enlist in the US military to “prove” the loyalty of Japanese Americans, while his sister Keiko (referred to as Kei, and played by the force of nature, Broadway legend Lea Salonga) organizes acts of civil disobedience from within the camp. Their father Tatsuo Kimura (Christopheren Nomura) – a first-generation immigrant who advises caution — is imprisoned in the stockades after he becomes a “no-no” responder to the Loyalty Questionnaire. Frankie Suzuki (Michael Lee) is Kei’s romantic love interest, and the second-generation “No-No Boy” whose acts of rebellion are anything but civil, while George Takei’s Ojii-Chan embodies the quiet defiance of incarcerees who refused to be broken by the barbed wire, and instead created art and beauty out of the harshness of the camp environment.

“Allegiance” capably takes the conventions of the musical genre and applies it to the weighty topic of Japanese American incarceration. Jay Kuo’s score deserves particular note: “Allegiance” moves seamlessly between 40’s era (implicitly coded “American” and “patriotic”) swing and big band, and traditionally Japanese musical language, smartly blending both into a musical that evokes what the Asian American identity might authentically sound like if rendered in songbook form.

Lea Salonga is enthralling, haunting, and technically impeccable as Kei, whose character trajectory offers a soft-spoken but unapologetic portrayal of 1940’s era Asian American feminism. As a longtime fan of her work, I was drawn to “Allegiance” in no small part as an opportunity to see Salonga in live performance; I was not disappointed — Salonga essentially anchors the show with her incontrovertible talent. What was more surprising was Telly Leung’s performance. Leung is a younger Broadway actor who could easily get overshadowed as a co-lead opposite Salonga, yet Leung shows by his performance that he is a rising star fully capable of holding his own in the presence of a living legend. As Sammy, Leung’s boyishness is infectious while his brash patriotism is compelling, if purposefully hard to reconcile with the fact that he and his family have been imprisoned by the very government he hopes to serve in war. Michael Lee’s Frankie is effortlessly charming, and provides among the best pop culture distillations of the “No-No Boy” archetype in mainstream pop culture. As an older Sammy, Takei was somewhat wooden in the performance I attended (he can hardly be blamed, it was the last performance of the weekend), but fantastic and funny as Ojii-Chan.

“Allegiance” does make a few missteps, however. A romance between Sammy and camp nurse Hannah Campbell (Katie Rose Clarke) feels shoe-horned. More frustrating, Hannah’s character – who seems to exist largely to serve as a sympathetic character to capture the interest of White audiences – becomes a vehicle whereby White Guilt and the White Savior Complex finds bizarre and unsettling articulation; this plot point takes a disappointing turn late in the second act that almost threatens to trivialize the musical’s larger lesson regarding Japanese American incarceration. “Allegiance” has also been plagued with controversy over its portrayal of Mike Masaoka and the Japanese American Citizen’s League. Having now seen the show, this is no baseless criticism: Masaoka – who urged compliance with the incarceration orders with an eye to making change from within America’s seats of power — is a fascinating and complicated figure in Japanese American history. But in “Allegiance”, that complexity is flattened away entirely. Masaoka voices defenses of incarceration while limited on-stage time is devoted to exploring his own conflicting emotions around becoming a pro-Establishment spokesperson for the camps. “Allegiance” deliberately refuses to give the audience a traditional villain (whether with regard to Frankie, Sammy, or even Hannah), but the lack of attention to Masaoka’s character makes it easy for audiences to slip Masaoka into that role. (Masaoka is portrayed by Greg Watanabe, who to his credit does his best with the limited material he is given to work with).

In general, “Allegiance” gives complex topics in Japanese American history a whirlwind treatment; writers have already commented on historical liberties and oversimplifications taken to force the fit. For those like myself who have already cultivated a familiarity with this subject matter, the musical can wander into the realm of the pedantic, akin to paying a hundred bucks to watch a fast-paced primer in Asian American History 101 (now with song and dance!).

But, I went to “Allegiance” with two well-read, progressive friends who reminded me that for them and for the vast majority of Americans, the intricacies of Japanese American incarceration is not familiar. Most Americans don’t learn about the camps in high school, and if the 40% who have a college degree are exposed to this material in college, it is only in cursory fashion. The JACL, 442nd, and No-No Boys are not familiar to most Americans.

Ultimately, this musical is not for me; it is for these Americans. “Allegiance” is a synthesis of our history into an emotional teaching moment for audiences who – as my friend reflected – only learn about Japanese American incarceration through its rare appearances in films like “Karate Kid”. For my friends, this musical was a powerful, educational, and deeply angering show, and for this reason I believe it is something that everyone must see. “Allegiance”’s narrative imperfections would be offset if it wasn’t one of the only mainstream projects to tell this story; if, there was simply more material that tackled this history in different ways. Indeed, we collectively thought that the downstairs gift shop should pair their sales of t-shirts and hats with a few classic Asian American texts on incarceration history (including the book written in association with this musical). We discussed the value of filming a version of the musical to make it accessible for students and adults priced out of attending the show live.

It is noteworthy that “Allegiance” created such an immediate curiousity of — and emotional connection to — Japanese American incarcerees in two audience members who didn’t walk in boasting existing familiarity with this subject. We could ask for no better endorsement for why “Allegiance” is a politically necessary and valuable show than that.

“Allegiance” is a good musical, but it is a better tool for reflecting on a dark moment in our collective history by infusing the teaching of our stories with the souls and songs of those who lived it. As such, “Allegiance” is worthy of our immediate support.

For more information and to purchase tickets: please check out AllegianceMusical.com