This post was published hours before the verdict in the Rekia Boyd manslaughter trial was announced. This post has been updated to reflect the outcome of that trial.

Earlier this month, 50 year old Walter Scott was shot and killed by North Charleston police officer Michael Thomas Slager following a routine traffic stop for a broken tail-light. Slager’s cruiser dash-cam shows that Scott — who was Black and unarmed — fled his car moments after being stopped. Slager gave chase and says he hit Scott with his Taser. Scott again fled, and that’s when Slager pulled out his handgun and fired eight shots from 20 feet away. Five hit Scott from behind, fatally wounding him.

We know these details of Walter Scott’s final moments because of eyewitness video captured by Feidin Santana (embedded after the jump). Understandably, many have focused on the first few minutes of the video: Scott and Slager are seen in the middle of a physical altercation. A black object drops to the ground while Scott turns to flee. He breaks into a determined run. Slager reaches for his gun and pauses, then fires seven times in rapid succession into Scott’s back. A momentary silence, and then Slager fires one final shot. Scott crumples to the ground.

This is easily the most gut-wrenching moment of the Walter Scott shooting video; but, it is not the only remarkable moment. There is a second portion of the video that also demands our attention.

A minute after Scott falls to the ground, Slager radios his dispatcher saying he shot a suspect who went for his Taser. Then, after he handcuffs an unresponsive Scott, Slager jogs back the 20 metres to the site of the initial altercation. He picks up the black object that fell to the ground. As a second officer arrives on the scene, Slager strides back and casually drops the object — his Taser — next to Scott’s prone body.

Later, Slager claimed through his lawyer that Walter Scott was shot after he allegedly overpowered Slager. Slager claimed he “felt threatened” when Scott got control of Slager’s Taser. That narrative, combined with Slager’s moving of his Taser from its original position, might have been accepted as the official account regarding Walter Scott’s death — had it not been for Santana’s surreptitious cellphone footage.

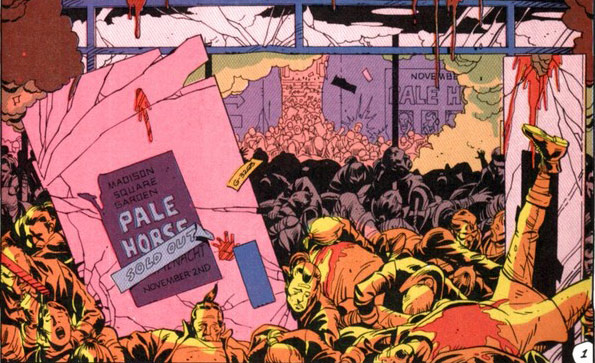

In 1986, acclaimed writer Alan Moore penned the landmark graphic novel Watchmen, which went on to be named one of Time Magazine’s top 100 English-language novels of the 20th century and to receive a Hugo award in 1988. Watchmen chronicles the story of an aging cadre of vigilante superheroes: self-appointed enforcers of justice who — empowered by society’s trust in their honour and integrity, and reinforced by the public’s fear of their superhuman abilities — serve as humanity’s moral judge, jury, and executioner.

Yet, over the course of the book, we witness each hero commit crimes of disturbing proportion: rape, assault, murder, terrorism and genocide. The central question of Moore’s book asks, “Who watches the Watchmen?”. It is a contemporary exploration of the same philosophical question that plagued Roman poet Juvenal nearly two thousand years ago, when he asked: “Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?“.

It is tempting to place our total faith in order, and in the integrity of those we appoint to enforce that rule of law. However, Moore cautions us to remember: our system is only as infallible as the enforcers we empower to serve that role. When we grant absolute power with no oversight to a select few, we simultaneously grant the possibility of total order and absolute destruction.

Recently, a New York Times article suggested that police unions increasingly believe that law enforcement is under public attack. Whether bemoaning the “professional race agitators” or civilian protesters, police today commonly believe they are part of an “alienated subculture” that has become the target of widespread public maligning.

This perspective misrepresents the position of someone like myself. To ask for greater accountability and oversight of our law enforcement is not to blindly criticize our police. Rather, it is to recognize that this country is founded upon the wisdom of a system built with checks and balances, and that this philosophy must also extend to our criminal justice system.

We place an incredible trust in our police officers. We arm police with lethal force and charge them to enforce the law against the citizenry. We also empower police officers with the presumption of not only justice, but also the truth. In the wake of the Michael Brown shooting, we saw how the testimony of a single police officer was granted greater weight than that of over twenty eyewitnesses, even though no person’s testimony was either unchanged over the course of the investigation, or entirely consistent with forensic evidence. In the 2012 shooting of unarmed Black woman Rekia Boyd, off-duty Chicago police detective Dante Servin claimed he opened fire into a crowd of bystanders after he says one — Antonio Cross– pulled out a gun and pointed it at Servin while charging him; assault charges against Cross were soon dropped, and the object Cross was holding was actually a cellphone.

It is as if we forget that law enforcement officers are not superhuman aliens with the power of a dozen Greek gods, an unbreakable moral code, and a penchant for blue-and-red tights. Instead, police officers are people, subject to the same fallibility as any other person. They are equally as capable of being motivated by temptation, self-preservation, or outright criminal deviancy as those whom we ask them to police. They are — by accident or intent — no more reliable narrators of the truth than anyone else.

We have seen ample evidence of this. In Officer Darren Wilson’s testimony in the Michael Brown shooting, Wilson claims Brown charged him while shrugging off multiple bullet wounds before he was killed by a shot in the head at close range. Yet, no forensic evidence supports this aspect of his testimony. NYPD Officer Daniel Pantaleo testified before a grand jury that he was employing a legal wrestling move before his arm shifted around Eric Garner’s neck, even though eyewitness video shows that his arm immediately adopted a chokehold position and never moved until Garner collapsed. The officers who shot 12-year old Tamir Rice claimed they told him to halt multiple times before opening fire, yet surveillance footage shows that the first shot was fired within seconds of police arrival on the scene, while the police cruiser was still in motion.

And finally, in the above video, we see the casual tampering of evidence by Officer Michael Slager — whether to remove physical evidence that the Taser was dropped by a fleeing Scott or to plant it on his prone body — all apparently to corroborate Slager’s initial account of the incident.

What becomes clear is that the question — who watches the Watchmen? — is not just the stuff of comic books; it is a central political question of our times.

Given this history of unreliable recollection, one must ask why we continue to rely almost exclusively on police accounts of fateful civilian shootings. In the countless police shooting for which we do not have eyewitness video, why do we trust police testimony as credible reflections of the truth? Why are we more inclined to believe police who said that Amandou Diallo was ordered to stop before he was fatally shot 41 times when he reached into his pocket for his identification? Why do we trust the testimony of the Minnesota police officer who claimed that Fong Lee was armed and dangerous over surveillance video showing him running for his life and over the claims of those who believe a gun was planted on Lee’s body after his death? Perhaps Officer Peter Liang’s shooting of unarmed civilian Akai Gurley was an accident, but why are some of us so opposed to scrutiny of this testimony that they decry the mere spotlight of a criminal trial?

It is clear that police perform a dangerous task, and that the duties we ask of them should not be given lightly. But, it is also clear that police are capable of misremembering the facts, or even lying about or tampering with evidence (as we see Slager do in Santana’s video, above). Yet we routinely refuse to build a credible system of oversight that at once honours police for their service, while acknowledging the simple fallibility that comes with their humanity.

For many in the public sphere, we have framed the question of police accountability around solutions of greater police surveillance. In the wake of Eric Garner’s death, I (like many pundits) asked if it was time to install body cameras on every police officer. Dashcam video has been useful in many cases to provide an objective description of events. Bipartisan efforts to mandate police wear body cameras has broad public approval. However, logistic and privacy concerns aside, police body cameras are not a panacea; last year, a New Orleans police officer turned off her body camera moments before shooting a man in the head, killing him.

Perhaps, then, the solution lies with civilian watchdogs of police action. Walter Scott’s case would have been relegated to a brief report in the North Charleston police blotter had it not been for Feidin Santana’s quick reflexes and his smartphone, not to mention his sense of social justice. Yet, not only does the legal right to videotape police remain uncertain with regard to the courts, but hanging the full weight of police accountability around the neck of civilian bystanders seems a frightful and undue burden placed on the public that would essentially hold citizens responsible for bad behaviour by cops.

And so, I argue that thinking about this in the context of police surveillance is thinking too small. We don’t just need body cameras. We don’t just need an established legal right to videotape police. What we need is a more fundamental, more radical shift in how we view our police. We need to stop treating police like paragons, and start treating police like people.

This need not be contemptuous of individual officers, no more so than we consider Congressional checks-and-balances of the power of the Executive branch an indictment of the person elected as president. A comprehensive outside review for law enforcement is no more a distrust of individual police than the U.S. Constitution reflects an abhorrence of the integrity of elected officials. Our political system largely works because no single branch wields unchecked power; why is the same not commonly held to be a necessary truism for law enforcement?

For some, police accountability already exists in the form of internal affairs; or, the police who police the police. Yet, we repeatedly witness the failures of internal reviews to arrive at meaningful fairness. Whether in the form of military court martials or academic hearings for accused on-campus rapists, justice is rarely found behind the closed doors of smoke-filled backrooms. It defies common sense to defend a system where we trust authority to regulate itself, yet this is our status quo when it comes to law enforcement.

Instead, what we need is greater support for a system of outside review for police action, via the legal system. An indictment — which allows a criminal trial to proceed — is a necessary first step that subjects law enforcement officers to outside review and scrutiny for their actions, specifically under situations of suspicious civilian deaths. It is not a malignment of police officers; it is a necessary, long overdue check and balance of police power. But this, too, is still not enough.

Late yesterday, off-duty Chicago police detective Dante Servin was found innocent of manslaughter and reckless endangerment for firing his unregistered handgun into an unarmed crowd of civilians, resulting in the death of 22-year-old Rekia Boyd by a gunshot wound to the head. What good are body cameras or eyewitness video if police officers are never indicted when we have record of them engaging in reckless and life-threatening behaviour? What good is a greater willingness to indict police officers before a grand jury if few are ever ultimately convicted of a crime?

It is time to crack open the thin blue shield we’ve currently allowed to wrap around our law enforcement officers, that protects them from any real consequences for their actions. Our courts of law must be willing to exonerate police when we find them innocent, but they also must be willing to convict when the evidence supports such a finding. This can only come with an end to our commonly-held presumption that police can only function when they go unchallenged, the alarming perspective touted by police unions right now. We instead must be willing to reimagine our law enforcement officers as capable of upholding what is right, but also of committing grave wrongs. We must no longer excuse the sins of individual police on the basis of our respect for the office they hold, alone. We must end our culture of assumed police infallibility, in favour of a system of formalized, and fair police accountability. We must start treating police like the people they are.

That’s why Darren Wilson should have been indicted. That’s why Daniel Pantaleo should have been indicted. That’s why Peter Liang should have been indicted. That’s why Michael Slager should be indicted. It is not only a racist system that would excuse police from accountability in the shooting death of civilians, it is also a terrifying system of unquestioned authority that we must not allow to continue.

And so, I urge us to ask: Who watches the Watchmen? In voicing the question alone, we realize that a more just society can only be achieved when we recognize that, firstly, someone must.