In December of last year, I predicted that Officer Peter Liang — the rookie New York Police Department cop who fatally shot Akai Gurley in a dark stairwell in the Louis H. Pink Houses complex — might be the first (and perhaps only) police officer indicted in the killing of an unarmed Black man when this issue was captivating national headlines.

Earlier that year, the killing of unarmed Black teen Michael Brown in Ferguson failed to result in an indictment for his killer Darren Wilson. Eric Garner’s death following an illegal chokehold administered by Daniel Pantaleo also did not produce an indictment. The shooting of unarmed John Crawford III in an Ohio Walmart by police did not result in an indictment. The shooting of unarmed college student Jordan Baker by police in Houston did not result in an indictment. No charges were even filed against the Utah police who shot and killed Darrien Hunt, cosplaying with a replica sword at the time of his death.

In fact, post-Ferguson analysis suggests that although any district attorney worth their weight can get a grand jury to “indict a ham sandwich“, this rule of thumb only seems to apply to civilians; indictment rates for police officers are markedly lower. Josh Voorhees estimates for Slate that most police officers are not indicted for on-the-job shootings: between 2005-2011, only 41 officers were ever indicted, which works out to only a little less than 7 indictments a year. Many sources further report that only 1 in 3 of those police officers who are actually indicted are ever convicted.

I predicted in December that Officer Peter Liang might be one of those police who would face indictment.

I find this case [of Akai Gurley’s shooting death at the hands of Officer Peter Liang] a symbolic testament to the precarious position that Asian Americans claim in the larger racial landscape of America. As a police officer, Peter Liang assumes the role of the authority figure. In essence, he becomes an embodiment of the Honorary White metaphor, and how it is used to police the behaviour of non-Asian people of colour. Yet, Liang also reminds of the fragility of Honorary Whiteness; how the status of the Honorary White is patronizingly and transiently bestowed; how it can be just as easily revoked when convenient.

…Doesn’t it say something about contemporary race relations’ divide-and-conquer tactics: built around the myth of Black criminality and reinforced by Asian Americans as the wedge, that could end up leaving one man of colour dead and another man of colour in jail as the sacrificial lamb?

Last week, Officer Liang was, in fact, indicted by a grand jury.

It is tempting as Asian Americans to decry this indictment. Officer Liang is “one of our own” — the son of Chinese American immigrants who worked hard to become a member of the New York Police Department. Indeed, a petition started on February 17 to WhiteHouse.gov (an entirely inappropriate place for this petition, by the way, given basic American civics) demanding that the Brooklyn District Attorney’s office drop the charges against Officer Liang garnered within a week well over the 100,000 signatures needed to require an official federal response.

An unknown fraction of those supporters are likely to be a subset of Chinese Americans whose views were articulated to the New York Times in an article earlier this week (emphasis added):

To them, second-degree manslaughter is too harsh a charge for what they say was a mistake. They accuse Mr. Thompson, a Democrat who has criticized law enforcement practices that affect minorities disproportionately, of bowing to political pressure after the officer linked to Mr. Garner’s death was not indicted.

“We all know this is a rookie cop who doesn’t know all the ropes,” said Doug Lee, a former chairman of the Chinese Cultural Association of Long Island. “We all know he was in a dangerous environment. Why did he charge a rookie cop with manslaughter, with the obvious intent of throwing him in jail?” He added, “This is a vicious attack on the family, and this is a vicious attack on the Chinese community.”

Okay, let’s be serious, here.

Grand jury proceedings are intended to determine the strength of the prosecution’s case, and to decide whether a case should proceed to trial. An indictment is not a determination of guilt; it is a determination of the possibility that a crime has been committed. It is an invitation for a full trial, which will invite further investigation and consideration into the circumstances of the death. It is an opportunity for the courts to grant justice to the victim’s family, or for the officer to be exonerated. This is a completely appropriate outcome for any suspicious death by a police officer’s hand.

I suspect that Peter Liang’s indictment does have something to do with his race, in so far that all jury proceedings — including grand jury proceedings — are innately subjective. Implicit racial bias broadly precludes empathy and sympathy with people of colour, which can manifest in a variety of forms such as being more likely to give White passengers a free rides on buses, particularly if they share the same race with the bus driver. When it comes to the legal system, we also already know that all-White juries are 16% more likely to convict a Black defendant than a White one. That Officer Liang was indicted should not be surprising to us: as a man of colour, Liang is marginally less likely to be viewed as a sympathetic figure by a jury than White officers are.

That doesn’t mean that Officer Liang shouldn’t have been indicted. Yes, the Asian American community has reason to be outraged about Officer Peter Liang’s indictment — but what we should be outraged by is not that Liang was indicted, but rather that Wilson, Pantaleo and countless other police officers who take the lives of unarmed civilians under questionable circumstances never are.

To argue that Peter Liang shouldn’t be indicted is to argue that, as a community, Asian Americans want to have the same privilege to shoot unarmed Black men without consequence as is currently afforded to White police officers.

In the quote I’ve excerpted above, Doug Lee of the Chinese Cultural Association of Long Island asks why a rookie cop would be charged with manslaughter in a shooting death that may or may not have been intentional. That would be because negligent activities — which might include conducting a vertical patrol against explicit orders, or failing to perform life-saving measures immediately following a shooting — that result in the death of a person might actually constitute manslaughter. That is for a jury to decide; which is what an indictment means. That’s how our legal system works.

Officer Liang’s indictment might be a wake-up call to some Asian Americans that we are still people of colour, and that our status as the wedge minority does not protect us from the consequences of a shooting. But it is unfathomable to me that some within our community are rallying around cries to withdraw the indictment of Officer Liang: why are we demanding the same license to kill that this society mistakenly affords to Whites?

As Asian Americans, our instinct is often to close ranks around our own. We must push back against the urge to do this uncritically, and in this case at direct odds with the larger campaign of racial justice and equality that seeks to end widespread police brutality and mass incarceration of people of colour, including many within our own community.

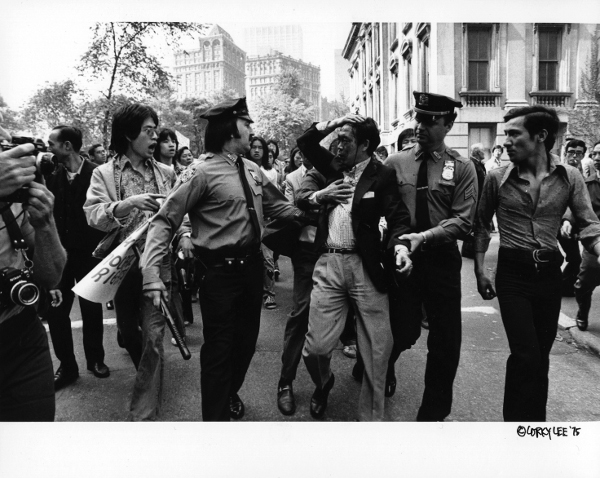

In the 1970’s and 1980’s, the country’s Asian American population was firmly engaged in the fight to end police brutality. Whether in New York City or San Francisco, Asian American youth — particularly young Chinese American men — were documenting repeated incidents of harassment and profiling at the hands of police officers. Our fathers, brothers and sons were stereotyped as gangsters, hoodlums and thugs. We staged multiple thousand-person marches and protests to speak out against police brutality targeting people of colour, and specifically Chinatown residents. Esther Wang writes for Talking Points Memo:

The story of another Chinese American, Peter from New York, helps us better understand why. Peter Yew was a 27-year-old engineer who, in 1975, was brutally beaten by police officers in Manhattan’s Chinatown, when he attempted to intervene after he saw them beating a 15-year-old kid whom they’d stopped for a traffic violation.

This prompted one of the largest anti-police violence demonstrations in New York City’s history, when as many as 20,000 New Yorkers, a majority of whom were Asian, took to the streets in protest. According to accounts from the time, virtually every store and factory in Chinatown closed on May 19 that year, the day of the largest demonstration, with signs saying “Closed to Protest Police Brutality” lining doors and windows in streets throughout the neighborhood.

Where is that outrage now?

In their reporting, the New York Times mistakenly pronounces the Asian American community as having “never been as politically active as blacks or Hispanics.” That statement is as untrue as it is ahistoric.

The AAPI community has a long and rich history of political activism, as old as our presence in this country. For much of that time, we have been on the side of racial, economic and gender equality. Our politics can ill-afford to evolve into the kind of inconsistent, antagonistic, nationalistic, and uncritical fervor that has too often swept segments of our community recently. We should seek to build our politics around an expansive and intersectional ideology of racial equality that opposes institutional racism in all its forms; not ground our political positions in the transient myopia of shared skin tone.

Yes, implicit racism might have been a factor in Officer Liang’s indictment. But, more often, Asian Americans are the victims — not the perpetrators — of racial profiling and police violence. This indictment is not “an attack on the Chinese community.” This indictment has provided undeniable evidence that White privilege exists, and that it protects White police officers in a way inaccessible by police officers of colour.

Racial equality is not to seek to elevate ourselves to unfair privilege over other minorities; it is to seek to dismantle that privilege, entirely.

The moral and common sense position here is not to oppose indictment of Officer Liang. As a community, we should be able to sympathize with Officer Liang and his family, while simultaneously acknowledging that a trial is a reasonable, necessary outcome for any incident involving the taking of a human life, whether intentional or not. Officer Liang may very well be a “sacrificial lamb” or “scapegoat” in the wake of a national conversation on excessive police force; the solution here is to demand more indictments, not less.

Being Asian should no more erase the consequences of causing the death of another human being than being White should.