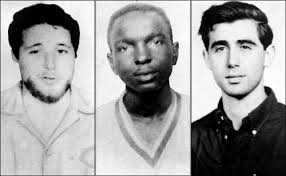

Yesterday, President Obama post-humously awarded James Chaney the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in this country. Chaney, along with Cornell students Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, was a freedom rider travelling through rural Mississippi to register Black voters when he was lynched and killed. He was 21.

Fifty years after his death and just hours after his memory was honoured, we received the heart-breaking (but entirely expected) verdict: there would be no justice for yet another Black man killed far too young. The justice system has failed Black America, yet again.

Last night, President Obama addressed the nation, urging us to recognize the country’s “enormous progress in race relations over the course of the past several decades.” The president is right — much has changed since the summer of 1964.

Yet, much has not.

James Earl Chaney was born in Meriden, Mississippi on May 30, 1943. Like many Black teenagers of his generation, Chaney became involved in the Civil Rights Movement seeking to end the systematized domestic terrorism against Black Americans that was Jim Crow segregation. At the age of 19, Chaney participated in the 1962 Freedom Ride from Tennessee to Greenville, Mississippi. By the age of 20, Chaney had joined several non-violent protests, and began working with a multi-racial group known as the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). By the age of 21, Chaney’s civil rights work would cost him his life.

On the eve of June 21, 1964 outside of Philadelphia, Mississippi, Chaney was traveling in a car with fellow CORE members Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman — Cornell University students who had journeyed to the South to participate in voter registration drives and non-violent protests; the three had also recently raised questions about police involvement in the racially motivated beating of other civil rights workers. That night, Chaney’s car was stopped by local Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price, allegedly on a minor traffic infraction. The three civil rights workers were taken to the Neshoba County Jail, where they were detained while denied access to their phone call.

Later that evening, Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman were inexplicably released. But, moments after resuming their travel, they were again stopped by flashing lights. They were hauled from their vehicle by two carloads of men, members of the local Ku Klux Klan. Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman were taken by force to a remote road where James Chaney was brutally chain-whipped. Then, all three young men were shot and killed, and buried in a shallow grave.

Chaney’s killers were not just faceless members of the KKK; Chaney’s killers included Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price, who co-opted his role in law enforcement to target, terrorize, and murder James Chaney and his colleagues. Price used the power of his office to stop Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner for an ostensibly legitimate reason. He used the power of his office to detain Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner without arrest or charge in a county jail until he could gather a mob together. Price used the power of his office — the flashing lights of his patrol car — to stop Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner for a second time. Price used the power of his office to murder James Chaney and his colleagues out of fear of Black empowerment.

The murder of James Chaney was tragically commonplace for the South in the 1960’s: Black civil rights workers were routinely beaten and even killed for their work. Most of the names of these lynching victims have now been lost to history. Yet, we remember James Chaney in part because he was killed alongside two college-educated White men from New York. For Chaney — and more specifically for Goodman and Schwerner — there was national outcry, and by December of 1964, Price and several other men were arrested.

It did not matter, however: in 1964, the state of Mississippi simply declined to bring murder charges against Price or his co-conspirators in the lynching. Federal prosecutors were successful in charging seven men (including Cecil Price) of the crime of depriving the three men of their civil rights, but none of those men served more than six years in jail for their crimes. Only in 2005 — an astounding 41 years after the initial killing — did anyone face state murder charges in the deaths of James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, or Michael Schwerner. Only Edgar Ray Killen, a local preacher and KKK member, faced any charges of six men who remained alive; Killen was eventually found guilty of state charges of manslaughter and sentenced to 60 years in prison.

Fifty years ago, in Chaney’s death, law enforcement abdicated its role to serve the public trust. Instead, fifty years ago, law enforcement served as a tool of terrorism for White supremacy; this role was upheld by the justice system’s abject refusal to acknowledge or prosecute any crime relating to the victim’s death. Fifty years ago, a young Black man lost his life at the hands of local law enforcement for the mere crime of being Black, and the justice system simply shrugged.

How much has changed? I would say — not enough.

Yesterday, the President honoured James Chaney’s memory while, hours later, the legal system again failed to value the life of a young Black man. Yesterday, a local prosecutor urged us to trust the process as he documented, in laborious detail, the many ways the process had failed. Yesterday, the President urged us to see our racial progress as another Black youth lay buried in dirt — dead at the hands of the men who should have been there to protect him — and another city in the South burned to ash.

Fifty years ago, Mississippi was unwilling to provide justice in the murder of James Chaney. Yesterday, Missouri was unwilling to provide justice in the murder of Michael Brown.

Yesterday, all we had to offer James Chaney was a Medal and an empty memory. Fifty years from now, is that all we will have for Michael Brown?