Last week, I reported about an updated survey jointly conducted by the National Asian American Survey (NAAS) and the Field Research Corporation that examined California voters’ attitudes towards affirmative action. That 2014 survey, led by Dr. Karthick Ramakrishnan, revealed that AAPI support for affirmative action policies have not shifted since 2012 (or the mid-nineties, under the auspices of a state referendum on affirmative action): 70% of our community’s registered voters still support affirmative action. These data corroborate similar findings from a 2001 survey conducted by a different group.

I wrote in my article that the findings of this latest 2014 study are likely to distress opponents of affirmative action. No surprise therefore that an op-ed appeared in the LA Times last week titled “Asian Americans would lose out under affirmative action“. The column is written by Yunlei Yang of the Silicon Valley Chinese Association and it is strongly critical of the 2014 NAAS survey results.

Yet, Yang’s column is also seriously flawed.

Taking Issue With Wording

Yang focuses the bulk of his criticism of the 2014 Field Research Poll on the wording of the question regarding affirmative action. He writes:

I find the poll question misleading and Ramakrishnan’s reasoning deeply flawed.

The original text of the poll question, written by a group Ramakrishnan directs, was, “Do you favor or oppose affirmative action programs designed to help blacks, women, and other minorities get better jobs and education?”

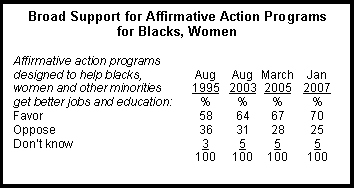

The question wording is lifted largely intact from a Pew Research Center poll on affirmative action that has been used as recently as 2007 (right). Pew is a nonpartisan survey group that conducts annual public opinion polls on a variety of subjects in America. In January of 2007, they found that 70% of survey respondents supported affirmative action, which they described as supporting “affirmative action programs designed to help blacks, women and other minorities get better jobs and education”. Your eyes do not deceive — this is exactly the same wording that Ramakrishnan used in his Field Research Poll.

The question wording is lifted largely intact from a Pew Research Center poll on affirmative action that has been used as recently as 2007 (right). Pew is a nonpartisan survey group that conducts annual public opinion polls on a variety of subjects in America. In January of 2007, they found that 70% of survey respondents supported affirmative action, which they described as supporting “affirmative action programs designed to help blacks, women and other minorities get better jobs and education”. Your eyes do not deceive — this is exactly the same wording that Ramakrishnan used in his Field Research Poll.

As recently as two years ago, Pew surveyed attitudes towards affirmative action with the following question: “In general, do you think affirmative action programs designed to increase the number of black and minority students on college campuses are a good thing or a bad thing?” While this represents a deviation in question wording from 2007, the deviation is not really substantial; the question is more focused towards the college campus sphere (where the bulk of disagreement on affirmative action is centred) and is a little more colloquial in tone (“good thing or bad thing”), but otherwise keeps the spirit of the question intact: affirmative action programs are still defined as programs “designed” to “help” or “increase” representation for minorities.

Yang (and others) take issue with this definition of affirmative action programs as provided in Ramakrishnan’s survey question, yet this definition is not drawn from a biased liberal source; instead, this language is actually drawn the case law on affirmative action, itself. The goal of affirmative action programs arrives in the form of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which reads:

In administering a program regarding which the recipient [of federal funding] has previously discriminated against persons on the ground of race, color, or national origin, the recipient must take affirmative action to overcome the effects of prior discrimination.

To draw upon a broad legal definition is essential; affirmative action programs are not limited just to race-conscious considerations in college admissions, but also to recruitment and retention programs.

It is only common sense, therefore, that if we wish to poll general attitudes on affirmative action programs, we must define what we mean by the phrase. Affirmative action, as defined by reams of case law and as articulated in contemporary layman’s terms, are simply programs designed to increase minority representation in the spheres of education and employment for a specific purpose — either to overcome discrimination (if one goes by the rationale of the 1964 Civil Rights Act) or to address the “compelling interest” of campus diversity (if one goes by the arguments presented in Grutter and subsequent Supreme Court decisions). Furthermore, to address the shift in rationale for affirmative action programs in the last twenty years, the 2012 NAAS survey polled respondents with multiple question wordings drawing on different aspects of affirmative action case law, and found no impact of question wording or presented rationale on survey responses. Thus, it becomes clear that this question wording of NAAS (and the more recent Field Research Poll) communicates a meaningful definition of affirmative action while it does not, itself, bias the survey outcome.

Yang also takes issue with the inclusion of “women” and “other minorities” in the NAAS survey question. Yet, affirmative action is not limited just to racial minorities: the Civil Rights Act established affirmative action programs as extending to racial and religious minorities, and subsequent case law expanded affirmative action programs to include women (via Title IX), the young and the old (via the Age Discrimination Act of 1967) and the disabled (via the 1990 Disabilities Act). To poll attitudes towards affirmative action while failing to acknowledge the full spectrum of identities to which affirmative action programs apply would be to provide an incomplete — and even leading — definition.

Yang chooses to simply ignore this careful and deliberately unbiased methodology to assert that a different (and unwieldy) question wording — “Do you favor or oppose race-based affirmative action programs with the intention to help blacks and some other minorities (excluding Asians) to get better education, at the expenses of whites and particularly Asians, who have been historically discriminated against? (Please note that according to some studies, these affirmative action programs may actually hurt students they are intended to help.)” — would be more appropriate and would yield a different result. I agree that this question would yield a different result, but I would further argue that any result obtained by this question would be biased and therefore meaningless. It is Yang’s question — not Ramakrishnan’s — that is leading with its partisan reference to Asian exclusion; moreover, Yang’s is asking a different thing.

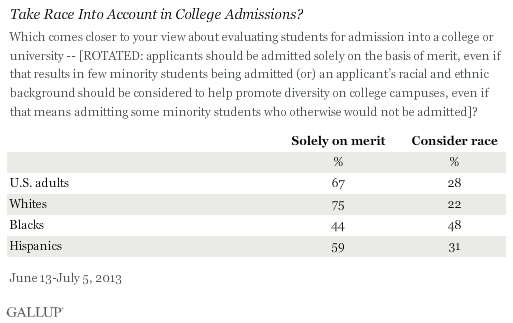

The questions posed by Pew and others are “principle” questions; the respondent is basically being asked whether or not they support the principle of affirmative action, irrespective of how those programs are administered. Yang’s question, on the other hand, is exactly the kind of overly specific “process” question that can — if administered carelessly — produce worthless results on this topic. Yang rightfully notes that “process” questions produce different answers on affirmative action than do “principle” questions; Pew also shows this in a 2009 survey on “racial preference”. Yet, “process” questions are fraught because in attempting to frame the process, they are readily biased by partisan interpretations of what the “process” actually is (as Yang’s own proposed question clearly demonstrates). For example, Yang cites a “more relevant” Gallup poll on “racial consideration” that shows two-thirds opposition, yet Yang fails to note that the Gallup poll asserted as part of the question that students admitted under affirmative action would also be less qualified, a highly contentious assumption.

Gallup is, also, itself problematic: Gallup does not represent itself as a non-partisan group, and has been heavily criticized for its conservative bias. In 2012, The Guardian noted that Gallup was one of only two major polling groups to consistently show President Obama trailing behind Republican challenger Mitt Romney in the presidential elections, which should raise questions about its methodology; the group has also predicted Republican outcomes, often incorrectly, in many other races over the years. On affirmative action, Gallup is not “more relevant”, it is just biased towards more conservative views.

The experienced pollster knows to simply avoid issues of introduced partisan bias in designing his or her question by focusing instead on a strict definition drawn from case law. That is, in fact, exactly what Pew and Ramakrishnan do: they offer a legal definition of these programs that focuses on their distinction from other admission and hiring policies by their specific goal: to address structural inaccess (to jobs and education) arising as a consequence of historic discrimination. To take issue with the presentation of this definition is to fundamentally misunderstand the legal history surrounding affirmative action, while advocating for an alternative that would produce the exact sort of cooked results Yang rails against.

A Hypocritical Focus on Self-Interest

When faced with a straightforward definition of affirmative action programs, Yang facetiously asks, “Who would not answer ‘yes’ to such a noble goal?”.

The answer is quite simple: one would answer “yes” to such a question if one supports affirmative action programs. And, indeed, Yang actually appears to support the principle of affirmative action, but only if those programs offer direct benefit to him or people like him. He writes (emphasis added):

[T]he Field Poll included employment, where the situation is vastly different from college admission and where Asian Americans often face discrimination and are underrepresented, especially in management and executive levels.

Later, Yang writes that he supports class-based affirmative action to correct for socioeconomic disadvantages (never mind the ample evidence showing that poor White and Asian students have greater access to privilege than wealthy Black or Latino kids, or that class-based affirmative action has been shown to be a poor substitute for race-conscious affirmative action). Thus, Yang appears to support the principle of affirmative action — programs that address the effects of systemic discrimination — but only as long as his in-group would be treated as an aggrieved minority. Thus, he makes room for affirmative action in employment to address anti-Asian American and Pacific Islander discrimination, but does not support affirmative action in education where he argues Asian Americans are “hurt” by such programs.

Yang fails to acknowledge that if affirmative action programs have value in federal contracting and hiring to address historic discrimination against multiple minorities (including Asians), than they must by extension also have the same value in college admissions to address historic discrimination against multiple minorities (including Asians and Pacific Islanders, but perhaps no longer including some East and South Asians). Yang further forgets that Asian Americans have historically been treated as a “preferred” group under race-conscious affirmative action programs, which have traditionally included Asian American (specifically Chinese and Japanese American) recruitment and retention programs to correct for decades-old anti-Asian exclusion.

To argue in favour of affirmative action programs in regards to employment, but to argue against affirmative action programs in college admissions — and to do so based only on the specific and contemporary circumstances of one’s in-group — is to be wildly hypocritical. It is to argue not against the morality of affirmative action, but in support of a “me-first” politic where the only rationale for one’s support of affirmative action is based entirely on whether or not it helps oneself get ahead.

Erasing the Voices of Southeast Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders

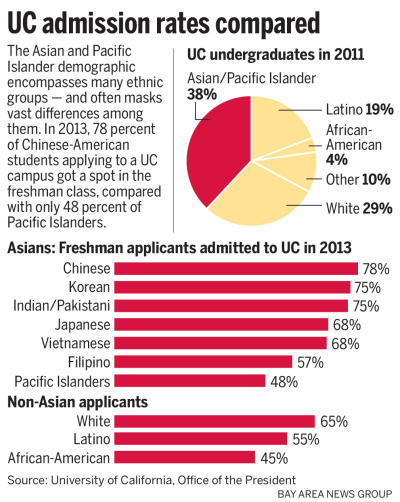

Yang also makes the startling generalization that “it is an indisputable fact that Asian Americans are hurt most by race-based affirmative action in college admissions“; yet, this is a “fact” that is actually quite heavily disputed. Setting aside for a minute reports that show that the kinds of informal interactions facilitated by campus diversity benefits all students, Yang applies a gross generalization of his own political narrative to the affirmative action debate and to the associated AAPI experience. The central thesis of his column — “Asian Americans would lose out under affirmative action” — is a shocking erasure of the multiplicity of the AAPI experience: Yang uses the term “Asian American” as synonymous with the experiences of East and South Asian American students, yet the term “Asian American” includes Southeast Asian Americans such as Cambodian, Hmong, Laotian and Filipino Americans who are significantly underrepresented in the UC school system. As reported in DiverseEducation.com last year, the National Commission on Asian-American and Pacific Islander Research in Education (CARE) found the following:

Yang also makes the startling generalization that “it is an indisputable fact that Asian Americans are hurt most by race-based affirmative action in college admissions“; yet, this is a “fact” that is actually quite heavily disputed. Setting aside for a minute reports that show that the kinds of informal interactions facilitated by campus diversity benefits all students, Yang applies a gross generalization of his own political narrative to the affirmative action debate and to the associated AAPI experience. The central thesis of his column — “Asian Americans would lose out under affirmative action” — is a shocking erasure of the multiplicity of the AAPI experience: Yang uses the term “Asian American” as synonymous with the experiences of East and South Asian American students, yet the term “Asian American” includes Southeast Asian Americans such as Cambodian, Hmong, Laotian and Filipino Americans who are significantly underrepresented in the UC school system. As reported in DiverseEducation.com last year, the National Commission on Asian-American and Pacific Islander Research in Education (CARE) found the following:

In the state of California, for example, Filipinos made up 25 percent of all AAPI residents in 2010, with Southeast Asians comprising 18 percent and Pacific Islanders 2 percent. But among all AAPI applicants to UC-Berkeley that year, Filipinos barely comprised 10 percent, Southeast Asians 13 percent and Pacific Islanders less than 1 percent.

Students of Southeast Asian American ethnicities are also Asian American, and our community maintains a strong alliance with those who identify as Pacific Islander; to write a column that simply erases their experiences from the “Asian American” narrative to instead buoy up a fantasy about “Asian American” exceptionalism on California’s college campuses should be alarming not just to supporters of affirmative action, but to any race activist interested in the project of inter-ethnic AAPI solidarity.

Standing Against Solidarity with Other Minorities

Speaking of solidarity, Yang disingenuously asserts that his opposition to affirmative action is actually in the best interest of African Americans and other minorities. To support this viewpoint, Yang cites the tired canard of Mismatch Theory.

Last, but not least, it’s highly questionable that affirmative action helps blacks and other minorities, which the poll takes as given. There is a famous book written by UCLA law professor Richard Sander and journalist Stuart Taylor, and the title says it all: “Mismatch: How Affirmative Action Hurts Students It’s Intended to Help, and Why Universities Won’t Admit It.”

Yang fails to offer any additional statements on Mismatch Theory other than the title of Sanders’ book (and that it is “famous”), so it’s left up to the imagination of the reader to determine which parts of Mismatch Theory Yang feels support his argument. Regardless, Yang fails to note that Sander’s book is scientifically flawed: it presents data that are largely not peer-reviewed and studies by other groups have reported the opposite to Sanders’ findings. The only peer-reviewed paper to come from Sanders’ body of work presents data based upon what he dubs “strong racial preference” — the equivalent of a >300 point difference in SAT score — that problematically assumes an explanation of racial preference (instead of other applicant factors) for admittance of minority students with low SAT scores. It further compares (White vs. Black) applicants across a range of SAT scores that is larger than typically seen for two applicants of these different races admitted to the same school. Even Sanders himself admits in an Intelligence Squared debate on NPR the difficulty in extrapolating from his data any predictions regarding the effect of “moderate” racial preference — a far more realistic scenario — on student performance. Critics of Sanders’ Mismatch Theory have pointed out several additional flaws in his work.

Yang goes on to cite changes in minority enrollment at the UC system, forgetting that absolute numbers do not take into account statewide changes in applicant population. He writes:

With Proposition 209 in effect since 1996, African Americans and Latinosnow account for a greater share of the University of California system’s overall admissions than when affirmative action was being practiced. In fact, Latinos’ numbers now exceed whites’ in UC freshman enrollment.

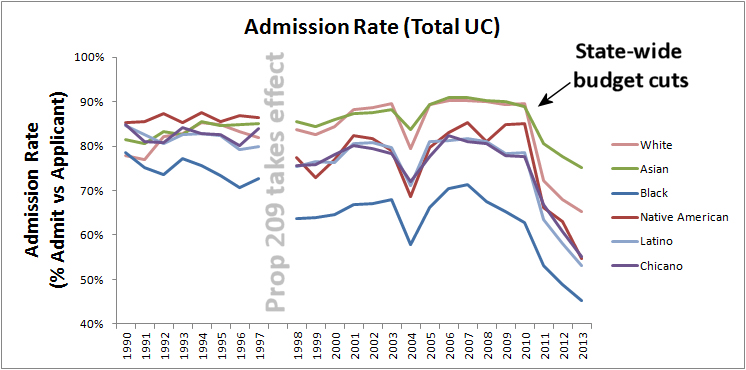

Yang simply fails to note that Latinos and Asian Americans are the fastest growing minority populations in the country, which includes the state of California; thus, consideration of enrollment numbers in the absence of this context produces disingenuous results. When one considers instead admission rate — the rate at which applicants of specific racial or ethnic backgrounds receive offer letters compared to the size of the applicant pool — we see that Proposition 209 had a devastating impact on minority admission rate, an effect that has persisted largely unchanged for the subsequent two decades.

Affirmative Action is a Complex Issue that Deserves Better Than This

Race-based affirmative action is a complex and emotional issue. It requires a calm, objective and honest discussion. Biased or misleading polls and reports only serve to needlessly drive wedges between different racial and ethnic communities.

On this, Yang and I agree. Affirmative action is, indeed, a complex and emotional issue that requires calm, objective and honest discussion. Yet, the SCA-5 debate has been characterized this past year with an alarming amount of misinformation and bias, and while Yang’s column is relatively tame by comparison, it nonetheless continues to draw upon the same shoddy arguments as were first presented in the heat of the debate earlier this year, largely without consideration for the arguments’ flaws. Affirmative action is a complex topic, one that challenges Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders to deeply consider not just our position as racial minorities but more fundamentally our position in the larger project of America: will we stand on the side of equal opportunity and education access, or will we advocate a myopic “me-first” politic that dismantles any possible solidarity with not only other people of colour but also with fellow Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders?

Yang’s column steadfastly ignores these issues to parrot the same tired arguments: the same link to that New York Times article purporting anti-Asian bias at elite universities coupled with the same vague hand-waving about college mismatch and the same uncontextualized UC enrollment numbers, sprinkled with a healthy dose of the same unspoken presumptions over Asian American cultural exceptionalism (as long as “Asian American” means “Chinese American”) and minority underachievement.

If the affirmative action debate has truly divided the AAPI community as deeply as it has, then the “other side” has a duty to meet a higher standard. It has a duty to present an argument that is better conceived than this.