By Guest Contributors: Avani Chhaya & Soham Sengupta

Truth is, you can inadvertently be both a good and bad desi.

A desi, an individual of South Asian descent, is dropped into two buckets. If you are a desi like us, you have probably also heard your aunties and uncles refer to “good” and “bad” desis. “Bad” desis are the lower-wage earners in South Asian communities, including teachers, taxi drivers, artists, convenience store workers and motel employees.

“This is your last year of teaching, right?” was the oft-repeated question from our parents. “To what?” was often our reply. Our parents’ responses came swift: “To other things.” This conversation plays out across South Asian households with desi parents wanting their children to become a Dr. or L.L.B — the “good” desi careers that were decidedly not our M.Ed’s. Those “other” occupations include medical school, business school, or law school — careers steeped in prestige. Teaching, on the other hand, is hardly given a nod of recognition and is more commonly regarded as a stepping-stone to bigger and better things.

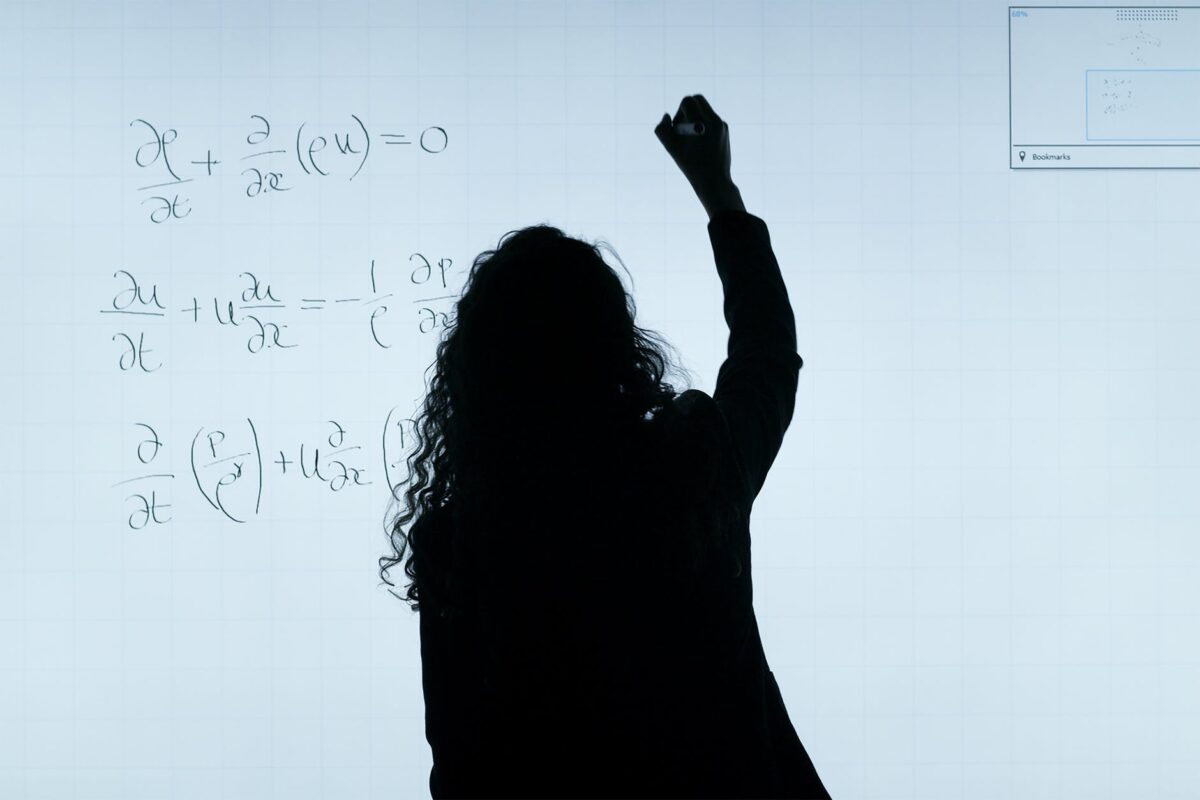

Even across sub-cultures within South Asian families, we value the promise of education but we do not value educators themselves.

Even across sub-cultures within South Asian families, we value the promise of education but we do not value educators themselves.

“Good” desis, on the other hand, are part of the upper echelon: the engineers, doctors and lawyers. This is a common trope in South Asian, immigrant households.

Growing up, we observed seemingly innocuous ways that members of our community used to differentiate between the “good” and “bad” desis. Those tools included: house size, car model, acquired degrees, English mastery, chosen career, annual salary, appearance, and, of course, the lack of an Indian accent. Think about how often the Indian “accent” is used as a punchline in American sitcoms with these characters being archetypally cast as the comical buffoon. Images of South Asian Americans either conjure up software engineers or gas station owners with heavy accents, falling into this good-bad dichotomy.

This good-bad binary has steadfast roots in religion. In Hinduism, the predominant religion for approximately 80 percent of Indians, for instance, there is a clear distinction between good and bad. It is built into the very ethos of the culture. In Hindu mythology, goodness is often represented by purity and light. Conversely, badness is often regarded with impurity and darkness. We see this paradox existing within different religions as well.

The fear of becoming a bad desi is sometimes used as a scolding or as a threat between South Asian parents and children. “Don’t be a rickshawala!” is a not-so-coded message to avoid professions like a rickshaw driver. This shame was placed upon children from the very beginning, connecting a lack of prestige with specific career pathways.

This bad desi ideology even extends to gig workers and to students studying the humanities and the arts. Are you going to waste your life in a frivolous career in the arts or humanities? Or, are you going to make something of yourself as a doctor or engineer? The implication from desi parents is clear. If you chose a career in the arts or humanities, you simply were not “good” enough to be in the sciences.

Exclusionary immigration policies are this country’s past and present. Starting from Bhagat Singh Thind, citizenship has eluded our ancestors up until 69 years ago. And yet, South Asians are trying to prove over and over again that they are not synonymous with struggle. But who are we trying to prove that to – ourselves or those folks from outside the community?

Higher-earning jobs, therefore, function as a status symbol to wash away our struggles, all for the sake of fitting in. South Asian kids aren’t necessarily predisposed toward math and sciences, but are encouraged and pushed to seek higher-paying careers which inevitably end up being in the domains of science, technology, engineering and math.

We have hope for the next generation of South Asian parents in stopping this vicious cycle of assigning value to individuals based on their career choices. As we see millennial South Asians getting married and starting their own families, let’s create a culture of respecting professions that fall outside of the prescribed doctor and engineer tracks.

We should not only challenge this good-bad polarity; we should actively seek to dismantle it. It’s far too easy to deem individuals as bad apples because stories of struggle are laced with personal pain for a diasporic people. Stories of struggle could be us; they are us.

We should not only challenge this good-bad polarity; we should actively seek to dismantle it.

Let us praise Rupi Kaur’s poetry, Mira Nair’s films, Sabyasachi Mukherjee’s fashion designs, and Mindy Kaling’s portrayals of three-dimensional, South Asian women. Let us also place value on the others – the ones who marched on the road less taken – the teachers, rideshare drivers, nonprofit leaders, convenience store workers and school leaders in our communities. Let us step back from ascribing value to particular professions and reflect how all jobs bring meaningful, often unseen, contributions to our larger society.

Because until we do that, we’re always going to be subconsciously thinking: Are we a good desi or a bad desi?

Avani Chhaya

Soham Sengupta

Avani Chhaya is a staff member and graduate student studying Educational Leadership & Policy at The University of Texas at Austin. She brings a background teaching English Language Arts. Her work has been featured in the Library Love Story and the Common Ground Series on KUT, ORANGE Magazine, VISIBLE Magazine and in Elisabet Ney’s Suffrage Now Exhibit.

Soham Sengupta is a program manager at Reading Partners Seattle. Prior to his current role, he was a 3rd grade teacher and successfully completed a stint as a Principal Intern at Seattle Public Schools while attaining a Masters in Educational Leadership & Policy at the University of Washington. His work continues to fuel and inform his development as a leader, educator, and learner – with particular focus on culturally responsive education as well as ensuring its equitable access for all students.

Learn more about Reappropriate’s guest writing program and submit your work here.