By: Hannah Han

DC Festival of Heroes: The Asian Superhero Collection is DC Comics’ newest comic book anthology celebrating Asian Superheroes comes just in time to celebrate Asian Pacifiic American heritage in May.

This is an exclusive interview with writer Gene Luen Yang and artist Bernard Chang, who have contributed a special story introducing a brand new DC superhero, Monkey Prince, as the main event of this 96-page anthology commemorating some of DC’s beloved Asian and Asian American characters.

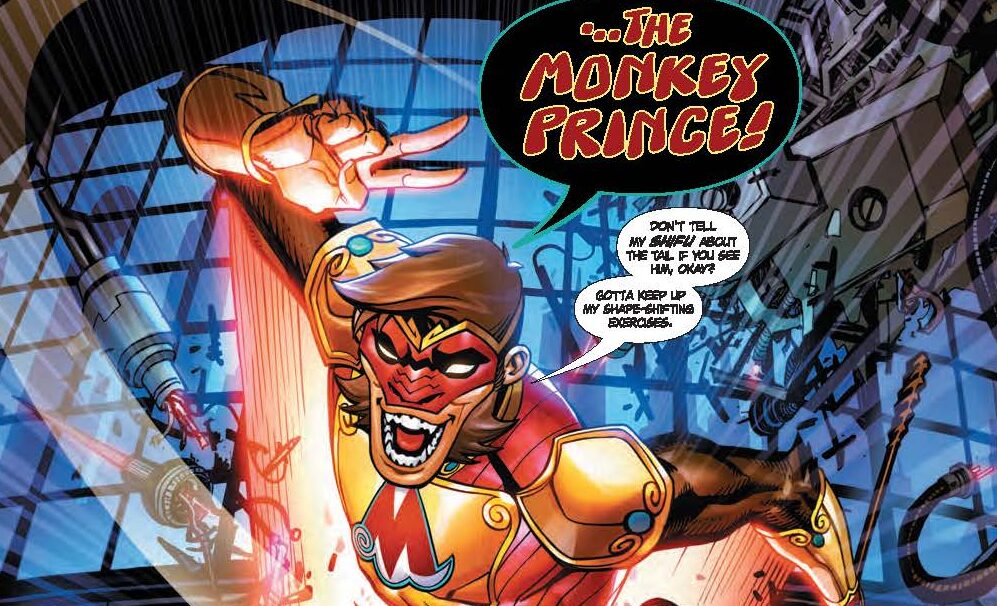

In the excerpt of The Monkey Prince Hates Superheroes from DC Festival of Heroes: The Asian Superhero Celebration, we only really got a small window into Monkey Prince’s world, but it’s really so richly depicted and vibrant, and I loved all of the references to Chinese mythology.

When you are drafting the story, what were your sources of inspiration, especially when giving Monkey Prince his distinct personality and background? Did you pull any inspiration from your own lives at any point?

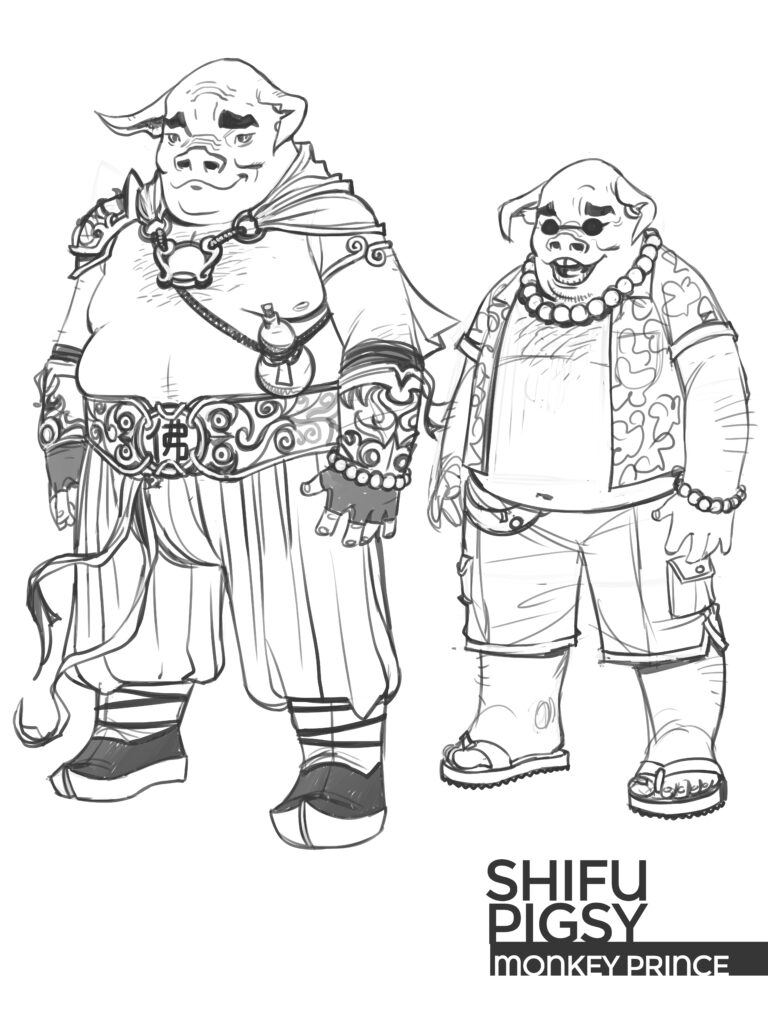

Gene Luen Yang: I think I speak for both Bernard and me that even though we worked on The Monkey Prince for a few months, we’ve actually been working on this story all of our lives. Bernard and I have thought about the Monkey King since we were little kids, since we’ve heard these stories from our parents. Again, being both Monkey King fans and superhero fans, we’ve thought about the connections between superhero stories and ancient Chinese mythology for years and years and years. In a lot of ways, this project felt like we were just pouring all the stuff out onto the page that has been with us since we were little kids.

Bernard Chang: Both of us grew up with our parents reading bedtime stories about the Monkey King to us. Growing up in America, we’re first introduced to a lot of American superheroes with these powers to fly and [with] super strength and all these things. And when our parents would read to us about the Monkey King, it was our own superhero that we could associate with.

GLY: There’s just so much overlap, I think, between the legend of the Monkey King [in] Journey to the West, the novel that first told his story, and the DC Universe. In terms of his personality, Monkey Prince’s personality really does come from the Monkey King. The Monkey King, throughout most of Journey to the West, is brash, and he’s arrogant, and he’s super confident in himself. He loves making jokes and tricking the people that he’s fighting, so we wanted our character to have a lot of that as well. One of the most exciting things about the story is that we actually get to treat the story told in Journey to the West as DC canon now. We’re treating it as if it happened. Wonder Woman was created out of mud in Themyscira, and around the same time, the Monkey King was escorting Tripitaka on his trip to India.

One of the most exciting things about the story is that we actually get to treat the story told in Journey to the West as DC canon now. We’re treating it as if it happened.

Gene Luen Yang

It’s really cool how the Monkey King story has been now integrated into what we consider canonical Western ideas of superheroes. I sort of wanted to broaden the scope of the question a bit, so my next question is for Bernard. Is there a particular character you related to most when you were drawing all of these different individuals?

BC: Well, going back to the bedtime stories, back then, [The Monkey King] was read to me in the form of a book, and I didn’t have a comic book version of The Monkey King. I couldn’t really read Chinese, so I was relying upon whatever my dad told me. I would go to sleep and try to imagine all of these fantastical things that had happened that he read to me, and that really spurred a lot of this imagination in my head.

Gene mentions Monkey King being mischievous, but he’s also a rebel, an independent person who was defying the gods. A lot of the imagery is just dream-like sequences. Even coming up with the logo that’s on his chest was something that I woke up from a nap when we were working on this, and I tried to incorporate the image of something with the clouds because Monkey King flew on a cloud. That design is actually very Asian-centric, in a sense. So a lot of this was just really inspiration born out of bedtime stories as a youth. It’s more about dreams. It’s more coming from my head and my heart, and not so much looking at what was existing, but trying to capture what was ‘childhood Bernard’ and what I could remember.

It’s more coming from my head and my heart, and not so much looking at what was existing, but trying to capture what was ‘childhood Bernard’ and what I could remember.

Bernard Chang

That was really lovely. I feel like I’ll be thinking about that for a while now. And I’m also wondering—what were the main challenges that you grappled with when trying to write and draw Asian American superheroes?

GLY: The thing is, when you look at the DC Universe, there actually are a whole bunch of Asian characters that date back to the very beginning of the DC universe [in] the late 1930s. They’re just all problematic. The name DC is named after Detective Comics, which is the longest running title of the company, and it’s really the longest running monthly series in America in existence. It’s been running continuously every month since, I think, 1937.

But if you look at the cover of Detective Comics, number one, it’s straight up “Yellow Peril” imagery. The character’s name is Ching Lung. So it seems like within the tradition of American comics, negative representations of Asian Americans are just baked into the DNA. When you’re looking for positive representation, it seems really sparse.

But in terms of just Asian characters, in general, there’re a whole bunch of them, [but they are] mostly problematic. So I think that’s the history that we have to contend with. The reason why we’re superhero fans, the reason why we love American superhero comics, is because of the history. We have this heart attachment, almost like this nostalgia, for all these superheroes that we grew up with. But as Asian American creators, we also have to recognize that some of that history is just not kind to us; it doesn’t show us as three-dimensional human beings. And I think that’s something that Bernard and I really want to do. It’s not just us; Jessica Chen, the editor whose idea was to do the DC Festival of Heroes [and] all of the Asian American creators that are involvedin the Festival of Heroes, we want to create three-dimensional Asian American characters and Asian characters within the DC Universe.

We have this heart attachment, almost like this nostalgia, for all these superheroes that we grew up with. But as Asian American creators, we also have to recognize that some of that history is just not kind to us; it doesn’t show us as three-dimensional human beings.

Gene Luen Yang

BC: Comic books, of all of the American pop culture mediums, is the one that I feel has probably the most Asian or Asian American representation in terms of the creators. Growing up as an artist in America as an immigrant, when you go to art schools, and you’re drawing from models, and you’re drawing from your life, and you’re drawing pictures of things, you’re taught foundationally from a Western perspective, especially when you’re drawing people. So, for me as an artist, at some point, I recognize that. As Asian American creator[s], we need to put our foot down, or take a step forward, and really begin to champion our own diversity and our own cause.

GLY: The thing is that, as Bernard said, there are a decent number of Asian American creators in American comics since the beginning. Bernard and I both grew up with Jim Lee; he was one of the biggest artists in the late 80s or early 90s. It’s just that on the page, it was different. There are plenty of Asian American artists; there’s a whole Filipino wave in the 1970s of comic book artists. But on the page, the representation was just not there until fairly recently.

Why wasn’t there more representation on the page until very recently, if there were a lot of creators who were of Asian American descent?

GLY: I mean, I think some of it was that they just didn’t think that Asian American characters would be able to sell, or the only way to sell Asian characters would be to have some kind of overlap with problematic representations. Like you could have a kung fu superhero like Shang-Chi, but you would have to emphasize his exoticism. Or you could have a yellowface kind of comic relief. In DC Comics [there] was a character called Chop Chop, who dates back to the 1940s, who was essentially a yellowface character. So I think there was a belief that you couldn’t market a three-dimensional Asian or Asian American character.

BC: Some of that is a call to action. When we grew up, our parents stereotypically [wanted] us to be lawyers, doctors, professors and businessmen. There are a lot of very talented Asian Americans, and we need to pursue that path. At the same time, it’s about taking risks. Gene took risks with his first projects. I remember my first project at Valiant Comics; they asked me to draw a monthly book, which is a full-time series. And I was 20 years old at the time.

I said [to them], “I’ll draw this book on one contingency: if you make the lead character an Asian American male who didn’t know kung fu, who was a lover, not a fighter.” Because, up until then, they had Asian characters, but again, like Gene said, they’re all kung fu guys. And we’re more than that. So it’s about stepping up. It’s about rising to the occasion and taking risks. And I applaud everyone here that has stepped up on this platform to make our voices heard.

GLY: That’s when I became aware of Bernard Chang, by the way, was during his run on Doctor Mirage from Valiant Comics. I was kind of shocked that he broke in. He broke in so young. I don’t even think you could even drink.

Wow, that’s so impressive.

GLY: Yeah, he’s one of the best.

We’re basically out of time, but if you guys are able to answer one more question, that’d be great. It relates to the last line of the comic excerpt. In the last line, Monkey Prince sees the video showing the fight with Shazam [a traditional Western superhero] and Dr. Sivana, and the Monkey Prince says, “Superheroes suck.” I thought that was so interesting that you decided to end on that particular line because this entire book is supposed to be about celebrating superheroes. I was just wondering why end on this line and what larger idea you were hoping to hit on with that.

GLY: The stories are built on tension, and we’re going to continue the Monkey Prince’s story after these twelve pages. This is just the very beginning, so I did want to introduce a tension that we could explore in future stories. And really, the thing that interests me the most about this project is the compare and contrast between Asian heroic traditions and Western heroic traditions. I think both of us want to explore, where do they meet and where do they diverge? So having the Monkey Prince hate superheroes, at least in the beginning, even though he’s wearing a very superhero kind of a costume, would be a fun way to explore that tension. Bernard, you want to jump in?

BC: I mean, this project in itself is a little bit of yuanfen. I’ve always admired Gene from afar, and to be able to collaborate with him on this has been a dream come true. But to also share this experience with all of these other amazing Asian American writers and artists and to also share the stories with [the public is incredible].

Thank you guys so much for speaking with me today. I really appreciate this opportunity, and you guys have such amazing answers.

GLY: Well, thank you, Hannah. Thank you for taking the time.

BC: Thanks for your time.

DC Festival of Heroes: The Asian Superhero Collection is on sale tomorrow, May 11.