By Guest Contributor: Mai Nguyen Do

The reveal of Watchmen’s Lady Trieu began as a promise of innovative retelling and reinvention. The numerous tweets referencing this mysterious woman compelled me to start watching the show, and her enigmatic character led me to believe that perhaps she would, like her namesake, ride storms for the sake of liberation. Instead of working towards reclamation and freedom for others, however, Trieu seeks to conquer the world only for herself.

Note: This post contains spoilers for the first season of HBO’s Watchmen.

Snippets of the 51st American state of Vietnam are sprinkled throughout Watchmen. The three-stripe Republic of South Vietnam flag has been reduced to two stripes, potentially a hint that Hanoi was decimated. A Borscht restaurant in Saigon bears the one-star, red-and-yellow design of today’s Socialist Republic of Vietnam flag, which might be a product of the Redford administration’s tolerance. The streets of Saigon look somewhat similar to what they do in the real present: very colorful, sidewalks crowded with stools and low tables, and somewhat neglected. It seems that even in a hypothetical scenario in which the United States won the war with the assistance of a supernatural being, Saigonese quality of life is very similar to how it actually is had this not happened. These conditions prompted me to speculate that Trieu would emerge as a revolutionary figure true to her namesake.

In the beginning of Watchmen’s season finale, Trieu’s mother Bian is shown reciting a famous quote attributed to the original Lady Trieu of ancient Vietnamese history:

“I want to ride the strong winds, crush the angry waves, slay the killer whales in the Eastern Sea, chase away the Wu army, reclaim the land, remove the yoke of slavery… I will not bend my back to be a slave.”

Bian’s actions, however, contradict the quote she recites. By impregnating herself with a sample of Veidt’s semen, Bian set forth a path for her daughter that remains defined by powerful men – or rather, one powerful man. Everything Watchmen’s Trieu does isn’t for the good of humankind or even for the Vietnamese people her namesake swore to defend. She acts primarily out of pride, ambition, spite, and an unfettered hunger for vengeance against her father. Even when she kills white supremacist leaders, she is primarily motivated by a desire to prove her worth to Veidt. This is not to say that a Vietnamese woman should be perpetually sacrificed for the common good, but rather that Trieu shows very little evidence she will ever act in full accordance with her own stated good intentions.

In retrospect, Trieu’s selfish ignorance was evident from the start. When she first appears in Episode 4 demanding that an Oklahoma couple give up their house and 40 acres of land, she states: “Legacy isn’t in land. It’s in blood, passed to us from our ancestors and by us to our children.”

This might seem like sound reasoning given her cultural background. Ancestor worship remains a core aspect of Vietnamese culture, even among those who practice theistic religions. However, the rejection of land as legacy within the context of ancestor worship only follows if one exclusively equates land to property. Someone who calls herself Trieu should know that legacy is not in land as in property, but rather land as in life. Land as in fiery earth and calm sea, where our fairy mother goddess and dragon king father came from, according to mythological legend. Land as in the rice fields where our ancestors’ bodies were buried and became one with the earth once again. For a woman whose name is derived from a revolutionary, she seems to be a fervent follower of the private property regime, in which all land is assumed to be possessed by default.

Trieu’s cruelty and her bastardization of concepts in Vietnamese culture such as ancestral worship are on subtle, but clear, display throughout Watchmen.

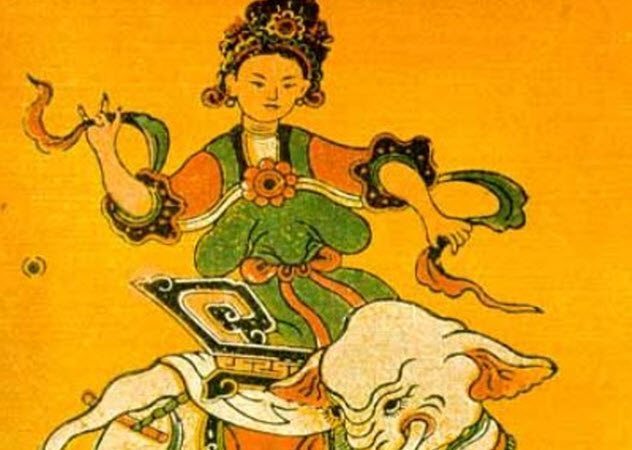

Trieu’s cruelty and her bastardization of concepts in Vietnamese culture such as ancestral worship are on subtle, but clear, display throughout Watchmen. Cloning her mother and making that clone her daughter is not entirely bizarre for a dystopian, science fiction work, but pumping highly traumatic memories into her daughter’s brain is inhumane at best. Not allowing her mother to simply remain dead also seems like an affront to the concept of ancestor worship, both because of the refusal to allow her mother to become an ancestor and because of the interference with what is supposed to be a straightforward process from death to deification. Additionally, using an elephant as a test subject is not just disturbing, but odd given that elephants are highly revered in Vietnamese culture: the original Lady Trieu, like the equally-legendary Trung Sisters of Vietnamese history, rode an elephant into war to defend her people.

There is some leeway to be afforded the show’s creator. Watchmen creator and showrunner Damon Lindelof said in a recent Entertainment Weekly interview that he wishes the Watchmen team had the time to explore Trieu’s character and more thoroughly discuss her childhood because it “would have been really interesting and maybe made us care a lot more about that character before she reached her inevitable end.” Still, while further exploration into Trieu’s past might reveal some explanation for her plans, it does not remove the contradictions between her name and her cruelty. Even if the original Lady Trieu was far from entirely merciful, she is deified by many Vietnamese women because of her focus on liberation. As such, there is no logical through-line or event sequence that could possibly connect the name “Lady Trieu” and domination.

Perhaps these discrepancies are meant to highlight how her name held so much potential in the beginning and meant nothing in the end. Perhaps Lady Trieu’s naming, her constant displays of cruelty, and her eventual fall are meant to be part of Watchmen’s overall project in its critique of our uncritical obsession with saviors.

Perhaps these discrepancies are meant to highlight how her name held so much potential in the beginning and meant nothing in the end. Perhaps Lady Trieu’s naming, her constant displays of cruelty, and her eventual fall are meant to be part of Watchmen’s overall project in its critique of our uncritical obsession with saviors. After all, throughout the time we see her, Trieu almost exclusively wears white, the Vietnamese color of mourning and death. It is indeed possible that Trieu is incredibly self-aware of these contradictions.

If the contradictions between Trieu’s naming and her ambitions are intentional, then the fault is not just in Watchmen’s execution of a potential critique of what happens when well-meaning people acquire immense power. Instead, the harm is in an insensitive and reckless appropriation of Vietnamese legend, of the tale of a female general who led a revolt atop a war elephant. The depiction of Trieu as someone who is superficially interested in her culture but completely uninterested in liberating her people is at minimum an insult to the legend of the original Lady Trieu.

The depiction of Trieu as someone who is superficially interested in her culture but completely uninterested in liberating her people is at minimum an insult to the legend of the original Lady Trieu.

Ultimately, Watchmen breaks the promise of Trieu’s naming. It breaks the promise of an imagined present in which a Vietnamese woman can break the shackles of oppression, in which Vietnam gains liberation not just from another empire, but from the millennia-long trappings of definition by war alone. It condemns a Vietnamese woman leader to destruction without even letting her die by her own hand as her namesake did.

Mai Nguyen Do is a Vietnamese American poet and researcher from Santa Clarita, California. Writing under her Vietnamese name of Đỗ Nguyên Mai, she is the author of Ghosts Still Walking (Platypus Press) and Battlefield Blooming (Sahtu Press). She studies Asian American politics as a PhD student in Political Science at the University of California, Riverside.

Learn more about Reappropriate’s guest writing program and submit your work here.