By Reappropriate Intern: V. Huynh

“I remember it wasn’t firecrackers… it was the sound of gunfire. And I remember seeing the blood everywhere on these kids. I remember seeing my cousin… gunned down.”

“It was the first moment I was reminded of the refugee camps where I grew up,” said Peejay, looking into the audience.

“The soldiers and the bandits,” he shook his head remembering the violence in the camps, “[It was] something I left behind, something my family left behind.”

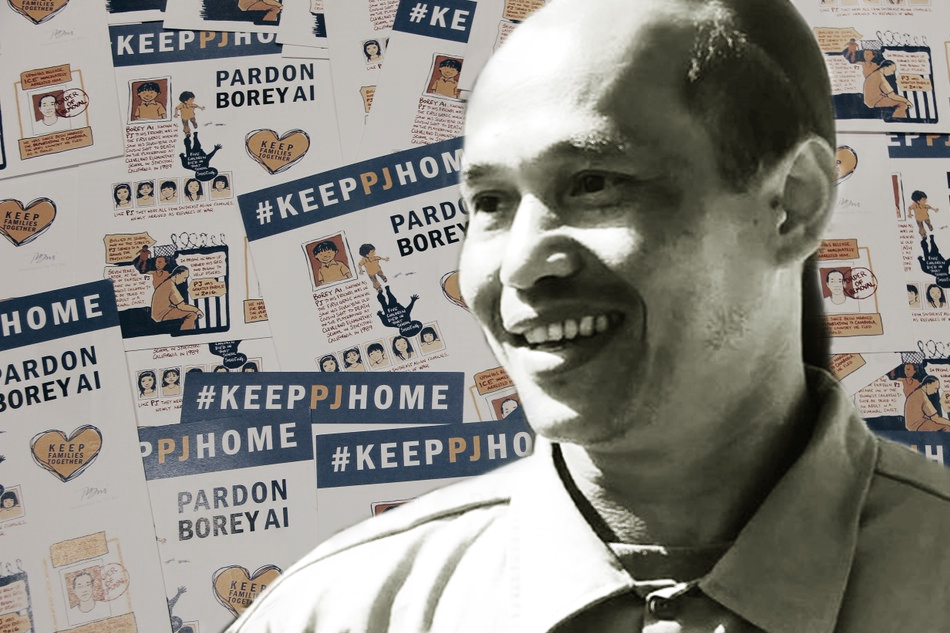

Borey Ai, also known as Peejay, has faced violence and discrimination from an early age. Fleeing war-torn Cambodia during the Vietnam War, the Ai family escaped to America as refugees. Upon their arrival in Stockton, California, however, Peejay struggled — as many Southeast Asian refugees did — in the face of racism, xenophobia, and local hate crimes. At the age of 14, Peejay was sentenced to 25 years in prison for second-degree murder. Immediately after his release, Peejay arrested by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and deportation proceedings were started against him. Now, Peejay faces the threat of deportation to a country he doesn’t know, even as Peejay is hoping his story will bring new awareness to the school-to-prison-to-deportation pipeline. With initiatives led by Nathaniel Tan and the Asian Prisoners Support Committee, the #BringPJHome and #KeepPJHome movements were born.

Braving a room filled with activists, community organizers, and supporters, Peejay retells his story at the #KeepPJHome event at the Asian Law Caucus’ office in San Francisco on July 12th, 2018. He retells that at 8 years old, Peejay witnessed his cousin shot to death at Cleveland Elementary School. Five other Southeast Asian refugees were also shot and killed that day, and an additional 29 kids were wounded and 1 teacher was killed.

He reflects: “I came to the U.S. because of a promise, the promise that ‘you have a bright future.’ But I didn’t feel that in the moment.” In his youth, Peejay grew up having to fend for himself from bullies — peers at school and members of the neighborhood — as well as from indifferent community members who did nothing to stop the violence he endured. His family of eight suffered from the aftereffects of the war, including trauma and poverty.

“I was isolated, I was alone,” Peejay trails off. Looking for family and acceptance, Peejay found a haven in a local gang at the age of 12. After he and his co-defendant robbed a local shop, months later, Peejay found out the shop owner had died in the incident. Peejay turned himself in immediately. At 14 years old, Peejay became one of the youngest juveniles to ever receive a sentence of 25 years in prison for second-degree murder.

“I remember walking in the prison yard, noticing I was different… everyone had tattoos, people were older, people were scary-looking, and I remember feeling very vulnerable,” he explained. He was only 14 years old.

But in 2014, during a dialogue with other incarcerated members, Peejay related to a story shared by another member who was talking about losing his daughter. “I [saw] his pain, his fear and his body… for the the first time in a long time, I reconnected with myself. I realized I did the same thing to another human being.”

During his time in prison, Peejay participated in several education and service programs. He served as a mentor, became a youth counselor, and received certifications in drug and alcohol, addiction, as well as domestic violence, and rape crisis counseling. He helped facilitate classes for Restoring Our Original True Selves (ROOTS), an initiative providing classes centered around ethnic studies and racial justice for other incarcerated members. Released on parole in 2016, Peejay explained how he was determined to change for the better. “I went back to school [and] got trades,” he said. “I wanted myself to make myself an asset.”

“For the young ones, so they don’t walk my path.”

But, as soon as Peejay set foot outside of the prison grounds, he was detained and arrested by ICE. Although he has since been released from ICE detention, today Peejay continues to be under threat of deportation. His family is devastated. When Peejay asked his mom how she felt during an interview, she reflected on all the family she lost in Cambodia.

“If they take you back, I would suffer all over again,” she said through tears.

* * *

When asked what kept him going, Peejay immediately refers to his mother. “I look back [at] my mom’s struggle [and]our people’s struggle. [If] they can do it, I can do it. It’s an honor to them, it’s in my blood.”

“One of the first steps is coming together,” says Peejay. “[For] three generations there was separation. Being refugees coming to this country, we were all separated and we continue to be treated [like we should] stay in separation. But, when we come together and ask for unity and start connecting to each other and communicating with each other, I feel like only then, can we begin the healing.”

“The Cambodian community has a lot of unresolved trauma that is passed onto the next generation, so we live with it all the time. I feel like that’s something we have to address.”

* * *

Peejay’s story is only one of thousands.

Since the arrival of thousands of refugees in the 1960’s, many Southeast Asian American youth have fallen victim to the school-to-prison-to-deportation pipeline.

Asian Prisoner Support Committee community organizer Nate Tan recounts: “I think from a very early age, all of us knew in some form and fashion that our people were being deported and we would only know after the fact. So we never knew why, and the stigma in the Cambodian community was that people who were getting deported deserved to be deported.”

When asked how we, as an Asian American community, should mobilize, Tan replies: “We want East Asian people to really smash the Model Minority myth and get rid of respectability politics. Take a break from the argument of affirmative action and media representation, and really focus on a community — the Southeast Asian and Cambodian community — that is really suffering under this administration. If the Asian American community really think that it’s really important to keep families together, they should know that other Asian American communities need their power and their movement to keep their families together from deportation. ”

To all audiences, Tan emphasizes, “Criminalization is not something you do. You become criminalized. Things make you a criminal. When you are at the crosshairs of poverty and racism and xenophobia, then the conditions are set up for you in your life to almost become criminal.”

When asked about how the movement began, Tan notes that there were movements around similar issues across the United States, but none had existed in California, which is known to have the largest Cambodian population outside of Cambodia.

“In the ROOTS class, [many expressed] pain they feel knowing they were going to get deported. The choices were always should I stay incarcerated or be deported, and these are really the only two options: incarcerated, and they get to stay and see their family or deported, they don’t see their family.

So I went to Asian Prisoner Support Committee (APSC) and said we should do something about this,” Tan explained. “And, Peejay was the one who was doing a lot of time, and I said, ‘let’s bring Peejay home.’”

The movement called for the use of social media to shed a light on the conditions of those imprisoned by ICE. The #BringPJHome movement gained momentum as community members rallied behind Peejay. And on May 2018, the movement celebrated Peejay’s release from ICE. But Peejay remains deportable, as are hundreds of other Cambodians.

As of June 2017, the largest group of Cambodians to be targeted in an ICE raid were quietly deported under Trump’s administration. This coming August, another round of deportations is said to follow. Now, the Asian Law Caucus (ALC) is calling on the community to come together and demand a pardon for PJ from California Governor Jerry Brown, which will make PJ safe from deportation. To secure more lasting change, the ALC is asking that the community support AB 2845, a California Assembly bill sponsored by Assemblymember Rob Bonta, which will create a Pardon and Commutation Panel that will streamline the pardoning process for PJ and many others.

The ALC urges community members to:

- Donate: You can donate to Asian Prisoner Support Committee here to help fund PJ’s anti-deportation campaign, and to stop further criminalization and deportations of Southeast Asian Community Members.

- Social Media Pressure: Tweet your support for PJ’s pardon campaign, AB 2845, and the rights of Southeast Asian refugees and immigrants everywhere to Governor Jerry Brown, Senator Atkins, and Senator Portantino. Use #BringPJHome, #KeepPJHome.

“Youth have a powerful voice. When they speak, people will hear it,” says Peejay. “If you hold those who have the power to make changes responsible, things will happen. So, reach out to legislators and representatives and really speak to them. Put some pressure on them.”

Reflecting on the campaign, everyone present, and everything that they’ve overcome together, Peejay’s eyes light up and his fists tighten. “I hope that people will pay attention.”

The plight of the Cambodian refugees and Southeast Asians everywhere asks us to remember that the seemingly distant issues about immigration rights, family rights, human rights are not so far from us. If we could take a moment to open our hearts, we will find that Peejay’s story can be apart of ours too.

Let’s #bringpjhome, and #keeppjhome.

You can also follow the campaign to #BringPJHome on Facebook.