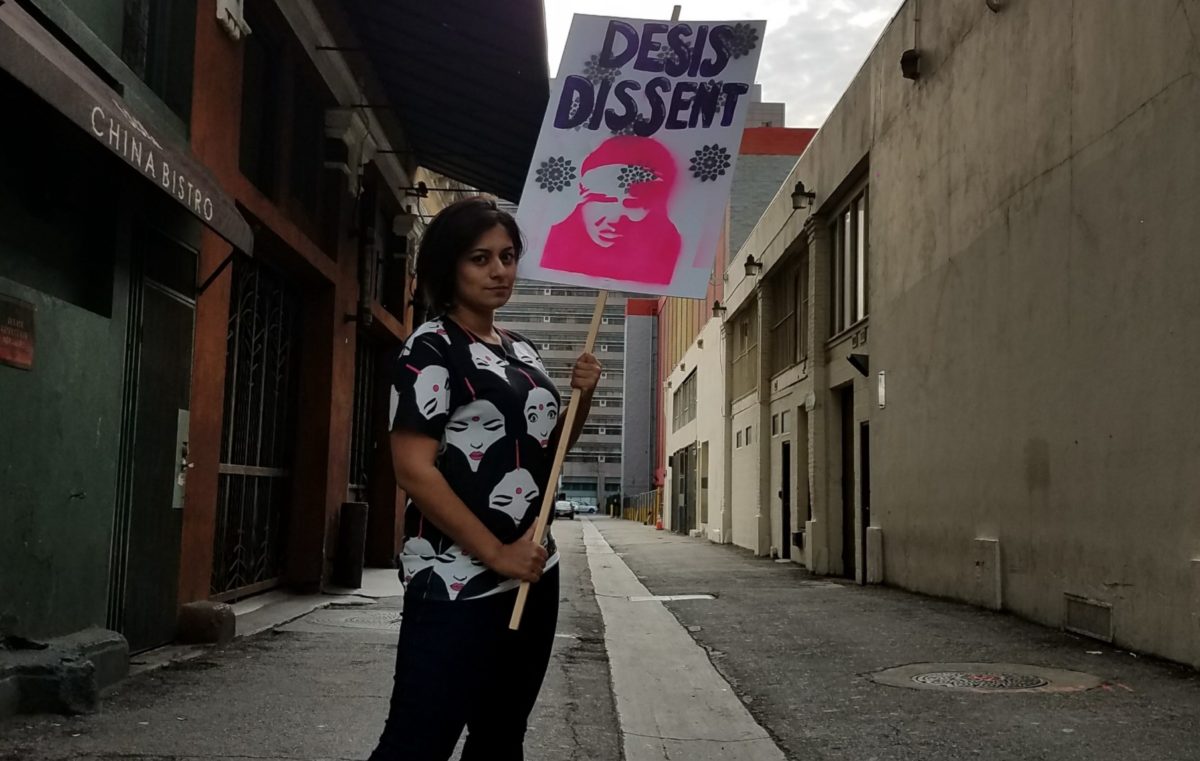

This essay was originally posted to Desis for Progress.

By: Tanzila “Taz” Ahmed (@tazzystar)

I first learn I am Asian when in the 3rd grade, I’m handed a standardized test. The first page, under my name asks me to mark one of the following?—?“White, Black, Hispanic, Asian or Other.” I raise my hand and ask my teacher what to fill out. She asks me what I am, and that I don’t know. She marks me as “Other.”

I first learn I am Asian when in the 3rd grade, I’m handed a standardized test. The first page, under my name asks me to mark one of the following?—?“White, Black, Hispanic, Asian or Other.” I raise my hand and ask my teacher what to fill out. She asks me what I am, and that I don’t know. She marks me as “Other.”

I go home and ask my Mom what I am. She doesn’t understand what I’m asking, or why I’m asking, or why this would be asked of me. She emphasizes that we are Bangladeshis. ‘But that’s not an option,’ I scream, frustrated. ‘Well, Bangladesh is next to India. So I guess you can put down Indian.’ ‘But that’s not an option either,’ I tantrum through tears. I am upset that a question so easy to answer for my classmates is so difficult for me. Mom looks at the options to choose from — ‘Since Bangladesh is on the continent of Asia, so that makes you Asian. That is technically accurate.’ I simmer down, and reflect on this statement. I don’t look like the other Asians in my school. I am skeptical of this statement.

The next day at school, I go to the globe and look for Bangladesh. Sure enough, I find it on the continent of Asia. So I guess that makes me Asian. My classmates tell me that I don’t look Asian, when I tell them. I show them the globe, and they are skeptical, too.

* * *

I first learn of Asian American history through other Asians. In grade school, we learn about Chinese laborers that came to work on the transcontinental railroads and the subsequent Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, created when the Yellow Peril fear of the Asian laborers by White people became too fierce. I learn of how immigrants came through Ellis Island and Angel Island, but am confused what island my family came through since they flew in on a plane. I learn about how the Japanese Americans were interned in camps, but in grade school we spend more time reading about Anne Frank and the concentration camps than we ever do on Manzanar, or Tule Lake, or any of the other camps scattered across America.

I still don’t see myself in these histories, not really. My kind of Asian — Bangladeshi American, South Asian American — don’t ever make it into the American history books, if only but a footnote. I find these versions of me in my geography books, maybe in a blurb about Gandhi, maybe a blurb on India’s Partition. ‘If this is American history, then how come there isn’t anything about my kind of American in here?’ I ask my grade school teacher. She tells me that my people are immigrants new to this country and have no history, even though I know I am not an immigrant and born here. I am skeptical of this statement.

I learn later, much later, South Asians did indeed come to America early. I had always been told that South Asian were new immigrants, coming after 1965’s Immigration and Nationality Act, imported for our brains as doctors and engineers. It’s not until I’m an adult, and searching through archives that I find a 17th century “wanted” newspaper ad in Richmond County looking for a runaway “East India Indian” man. I know that slaves came from Africa, but I didn’t know that slaves came from South Asia, too. The image states it was looking for Thomas Greenwich, a “well made fellow, about 5 feet 4 inches high, wears his own hair, which is long and black, has a thin visage, a very sly look and a remarkable set of fine white teeth.” I learn later, much later, that many East India Indians came over as indentured servants to the American colonies, “blending” into the free African American population when they won petition of their freedom. I find myself viscerally reacting to American History slave narrative after finding this out — I am sad that this is forgotten as a part of our Asian American history. I wonder about all the anti-blackness and how much that would change if they all only knew. I wonder how this feeds divisiveness into the model minority myth.

I become obsessed. I learn of other kinds of South Asians that existed in in America pre-1965. There are the Punjabi Sikh farmworkers that moved to the Central Valley of California to work on the farms. There are the gurus and yogis and charlatans that came to make money off of telling fortunes to the wealthy Whites. There are the ship-jumping stowaways who secretly imported ethnic goods from the motherland. I learn that South Asian men immigrated alone and couldn’t bring over wives, nor could they marry White women, so they married Mexican women in California and Black women in the South. I wonder how different my life would have been if I had known my history of being working class and slaves as South Asian in America went back hundreds of years — we are not just newly imported educated immigrants.

* * *

I learn about the Asian American movement before I learn that a South Asian American movement even exists. I first learn the modern day Asian American movement has roots in Vincent Chin’s murder in 1982. Severely beaten in Detroit leaving his bachelor party in a vicious hate crime — he was attacked by two White men who accused him of being a Japanese job stealer — they blamed him for the loss of their auto industry jobs. The murderers were given three years probation and fined $3,000 — it was this injustice that galvanized the modern day Asian American civil rights movement. I learn how this hate crime is tied back to the Yellow Peril fears in the early 1800s and how those are tied to the hate crimes against Japanese Americans in 1940s.

It’s not till later that I also learn that just the way Whites who were afraid of East Asian laborers, they were also afraid of South Asian laborers too. I learn of the 1907 Bellingham Race Riots in Washington state where the South Asian paper mill laborers are chased out by White laborers who are upset with jobs being taken from them.

In 2016, we see a rise in anti-Muslim/Brown hate crimes, propelled by the fear-mongering in the elections. The white supremacists are emboldened and every month on my podcast, we dedicate a moment to uplift hate crimes that happened — we talk about a stabbing of someone speaking Arabic, a mosque burning by white terrorists, people shot in the head over a parking spot. Almost every month, there is something new. Well-meaning liberals come up to me and say, ‘I can’t believe this is happening in America. Not in my America. How could something like this happen here?’ I stifle a laugh, as they point to their safety pin, unable to maintain polite decorum. White supremacists have been attacking South Asians for a long time — it’s been 110 years since the Bellingham Race Riots, didn’t you know? This is the storied marginalized history of America, it’s as American as it gets.

* * *

I learn about Asian American activists before I learn about South Asian American activists. I learn about Grace Lee Boggs and Yuri Kochiyama in same breath I learn of Malcolm X. I learn about Filipino farm worker Larry Itilong who worked side by side with Cesar Chavez. I learn about the Asian American zine called Gidra, published from 1969–1974. I am inspired by the world of the environmental justice organization Asian Pacific Environmental Network. I study Korematsu vs. United States case in grad school.

It’s not till later that I learn of the activism of the San Francisco-based Ghadar Party movement from 1913–1919. It is this seed of rebellion within these South Asian American men that eventually leads to an uprising in India against the British colonizers and India’s independence in 1947. I learn that the Ghadar Party valued written words, and had a newsletter of their own which they self-published on their own printing press and, when too dangerous to carry in print, they would memorize the words of the newsletter to spread the articles verbally. That hand cranked printing press is in the Sikh History Museum in Stockton, California today.

I learn of other South Asian American activists — the first South Asian congressman Dalip Singh Saund, instrumental in passing the Luce Celler Act which gave South Asians the ability to become citizens; the infamous Bhagat Singh Thind vs Supreme Court case of 1923 arguing for South Asians’ naturalization; and Black Panther activist and union organizer Kartar Dhillon. I learn of South Asian women activists abroad that shape my thinking, like England’s sari wearing union organizer Jayaben Desai; environmental justice organizer Vandana Shiva; and women’s rights activist Phoolan Devi, otherwise known as The Bandit Queen. I discover that I’m not alone and contemporary South Asian American activists exist. I make it a point to read them and learn from them, people like Vijay Prashad, Deepa Iyer, Biju Mathews, and Sunaina Maira. I make it a point to listen to music like Asian Dub Foundation, DJ Rekha, The Kominas, Mandeep Sethi and Saraswathi Jones.

In my 20s, I start a non-profit called South Asian American Voting Youth and pack the board with South Asian American activists my age that I have found and want to be involved. It is my first time finding like-minded South Asian Americans to organize with and it fills my sense of purpose in an addictive way. I keep finding more. I start writing on the South Asian American blog Sepia Mutiny and find more South Asian activists. I am a founding organizer of Bay Area Solidarity Summer where we equip South Asian American youth activists with the knowledge we now know and wish we had when we were their age. I organize with South Asians for Justice-Los Angeles, I organize with Vigilant Love, and I organize so much more. I write for ‘Love, Inshallah’, I write for ‘Good Girls Marry Doctors’, I write everywhere I can. I am obsessed with finding my people, and re-centering my stories and stories like mine. I do not want anyone else to grow up feeling as lonely from their stories and histories as I did.

Every step of the way I keep finding more and more like-minded people, more and more South Asian American activists, so that when people try to dismiss me by calling me an anomaly, I have receipts to show that this is actually our American activism legacy. We exist. We have always existed.

I am an Asian American, I am a South Asian American, I am a South Asian American Activist. We are not the perpetual other, and we’ve always belonged.

Tanzila “Taz” Ahmed is an activist, storyteller, and politico based in Los Angeles. She currently is a Campaign Strategist at the Asian American new media organizing group 18MillionRising. Taz was honored in 2016 as White House Champion of Change for AAPI Art and Storytelling. She is cohost of The #GoodMuslimBadMuslim Podcast that has been featured in Oprah Magazine, Wired, and Buzzfeed as well as live shows recorded at South by Southwest and the White House. An avid essayist, she had a monthly column called Radical Love and has written for Sepia Mutiny, Truthout, The Aerogram, The Nation, Left Turn Magazine, and more. She is published in the anthologies Modern Loss (2018), Six Words Fresh Off the Boat (2017), Good Girls Marry Doctors (2016), Love, Inshallah (2012) and poetry collection Coiled Serpent (2016). Her third poetry chapbook Emdash and Ellipses was published in early 2016. Taz curates Desi music at Mishthi Music where she co-produced Voices of Our Vote: My #AAPIVote Album (2016) and Beats for Bangladesh (2013). Her artwork was featured in Sharia Revoiced (2015), in Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center’s “H-1B” (2015), and Rebel Legacy: Activist Art from South Asian California (2015). She also makes disruptive art annually with #MuslimVDay Cards.

Write Back, Fight Back(#WriteBackFightBack) is a weekly essay series sponsored by 18MillionRising, Asian Americans Advancing Justice, and Reappropriate. It features emerging Asian American writers on topics of racial and social justice. New essays will appear every Thursday.