By Guest Contributor: Monique Jones (@moniqueblognet)

A version of this post first appeared on Just Add Color.

When I first wrote my article about BTS coming to the American Music Awards, I was excited to see this famous K-pop group that I’d heard so much about. I was happy that they would have the chance to perform on a major international stage like the AMAs. I believed that this appearance would serve as the biggest stepping stone yet for K-pop’s eventual domination of American airwaves. As I wrote on Twitter after BTS’ performance (and after I saw the crowd whipped into a frenzy), this must have been what seeing the Beatles for the first time was like.

BTS has been on a roll since their big AMAs debut. They’ve hob-knobbed with R&B it-boy Khalid, and they have released a track featuring Desiigner and Steve Aoki,”Mic Drop”. Everything’s going well; or, it’s going well for BTS, anyways.

The rest of K-pop, however, still hasn’t really “made it” in the States. While one might speculate as to the many reasons why K-pop has failed to penetrate the American music landscape — language barriers; stereotypes about Asian performers held by music executives; general American disinterest towards international music that isn’t British or Canadian — one major reason deserves more discussion: K-pop, as a whole, has a race problem.

So, how is BTS overcoming it?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tNtcYIo6N04

K-pop’s history includes many instances of anti-blackness, both intentional and unintentional. For example, there is the wearing blackface reminiscent of the ganguros of Japan, who self-identify with the black rapper image so much that they darken their skin, blurring the lines between wayward appreciation, fetishism, and straight offensiveness. There iscolorism, such as with some groups’ members poking fun at other groups’ members for their tan skin. There is intense fetishism of Blackness, which is one of the defining traits of K-pop. It colors how K-pop idols — and, how K-pop male idols, specifically — interact with Black men. For example, a K-pop idol who associates with a Black man can be perceived as getting an “all clear” or a “black card”, even if the idol lacks a true understanding of the culture they love and mimic. Fetishism of Blackness also colors how male idols interact with Black women. Yes, many K-pop idols — both male and female — love Beyonce, Rihanna, and Tinashe; and, some male idols even claim to prefer Black women as romantic interests. But, are Black women — rappers, dancers, and fans — seen as just hypersexual objects or are they seen as legitimate collaborators in a larger conversation around music and culture?

K-pop also frequently exoticizes the Black Rap image. Idols may dress in the “black rapper” style, affect a “blaccent,” and mimic notable rapper mannerisms. As shown by has-beens like Iggy Azalea, being blatantly fake will only get you so far.

In short, K-pop has both a credibility issue, as well as a sensitivity issue. Can K-pop fix these two problems and get firmly on the road towards American domination? It seems like if there’s any group to do it, BTS is definitely most prepared for the task. Through a trial-by-fire in the form of a reality show three years ago, BTS has gained the knowledge necessary to possibly become the first K-pop group to go beyond mimicry, and to instead develop a brand that openly and honestly respects its black musical forefathers and foremothers. This could go a long way towards winning over black America, and by extension, the rest of the country.

Fakery Versus Reality

It is unclear what people expected from BTS when they arrived for the AMAs; but, based on every interview they did in the week they were in Los Angeles, they clearly succeeded in winning hearts. Moreover, based on how they presented themselves, winning hearts and changing minds were their top priorities.

Of all K-pop groups, BTS most understands the racial hurdles they face in trying to cross over into the American music scene. They understand, for example, how members of the Asian diaspora in America face myriad stereotypes while trying to make it big in the music industry.

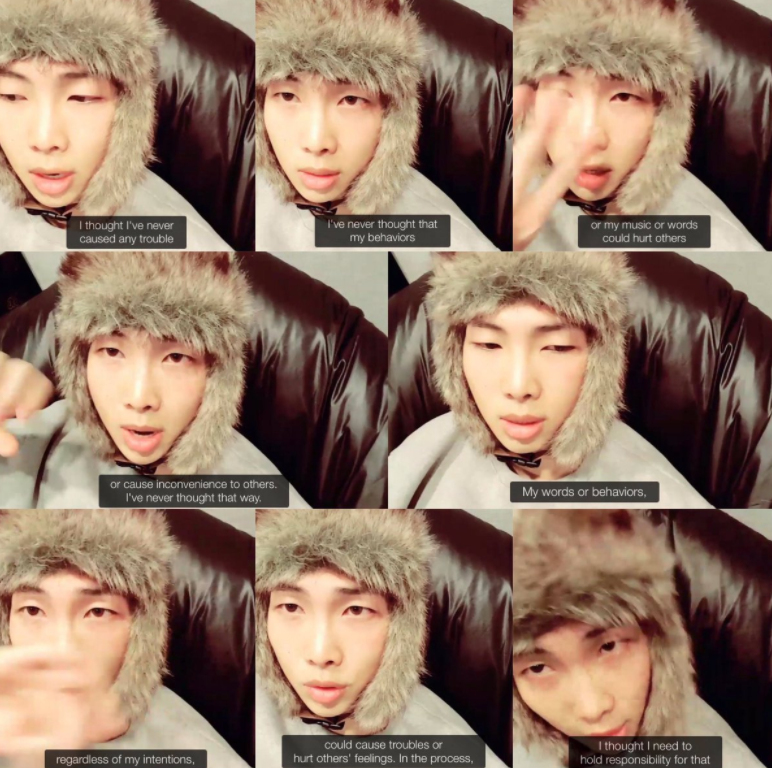

BTS group leader and rapper RM (formerly known as Rap Monster), seems particularly astute. Not only was he the group’s English-spokesperson during their brief stint in America during the AMAs, but he also knows enough about America’s stereotypes against Asian performers to comment on how the AMAs treated the band with respect.

“The AMAs didn’t treat us as a curious novelty from Asia, but showed us respect and treated us as an important part of the show,””he told Metro UK. “They put our performance right before Diana Ross, and we were introduced by the Chainsmokers, who are very popular in the United States. It was clear in many ways that they knew a lot about us and had prepared for our appearance for a long time.”

RM is different from what many Westerners perceive the K-pop idol to be. Aside from being highly intelligent — he has an IQ of 148 — he’s introspective and, as you’ll read later in this post, he actually seems to apply the lessons he’s learned from some of his more haunting mistakes. Also, his journey in the music industry, coupled with his personality, has imbued in him an “anti-mainstream” sensibility.

On top of that, he has credibility as a rapper that is hard to come by for many K-pop idols. Unlike other members of BTS, RM and fellow groupmate Suga cut their teeth in Korea’s underground rap scene. If you work your way up from the bottom, you’re bound to learn some things an idol class won’t teach you. RM has already had his credentials as a rapper questioned based onhis decision to join a boy band: in his cover of Drake’s “Too Much,” he addressed other rappers who have tried to start beef by calling him a “sell-out” In fact, many songs written by RM feature “the inner conflicts that Rap Monster, Suga and J-Hope have as idol rappers.”

BTS also boasts another unique experience relative to other K-pop groups: during the 2014 reality show American Hustle Life, the group underwent a military-style bootcamp on the history of hip-hop and rap from the legendary, Coolio. In that series, BTS members traveled to Los Angeles — the home turf of West Coast rap — to receive on-the-ground training from legends in R&B and hip-hop.

As journalist Blanca Méndez wrote for Noisey:

Though Rap Monster and his groupmates may be relatively well-versed in current hip-hop music, it’s hard to understand the music without fully understanding the culture. It’s even harder to do so in a place so far from the source, especially since, for a country that consumes and repackages hip-hop culture as much as it does, Korea has some serious issues with anti-blackness.

Many American pop and rap fans — particularly many Black American fans — remain skeptical of K-pop. Korea’s homogenous culture can perpetuate an ignorance of — or, in some cases, an apathy towards — anti-Black stereotypes and offensive words, such as the racist contexts of blackface and the “N”-word. Even BTS couldn’t escape making some of the same egregious mistakes that have befallen other K-pop idols. Early in their career, BTS had their own brushes with the “N”-word, which caused extreme controversy. A younger RM boasted that “talking black” was “a talent” he was good at. Until their education with the actual rap greats themselves, BTS was like any other K-pop group: problematic. Some fans even labeled them “racist.”

But what’s the difference between abject racism — which is apparent in Korea as well as n the rest of the world — versus plain ignorance? Ignorance certainly isn’t an excuse for bad behavior, especially since there are several K-pop idols who were actually born and raised in North America and who should therefore understand the racial implications of “playing black”, as it were; but, we should also consider when sincere ignorance occurs.

In my opinion, much of the way K-pop interacts with rap is similar to watching a child discover rap for the first time. For this child, everything about rap is “cool”. The child becomes obsessed with knowing every lyric (even the bad ones) and mimicking every body movement. The child doesn’t realize he’s parodying the culture he proclaims to idolize — until he goofs in front of an actual Black person. What happens next may depend on how that Black person chooses to react, but regardless, the child comes out the other side a different, and hopefully more aware, person. BTS got their own wake-up call during the first American Hustle Life episode, in which they found themselves in front of Coolio for the first time

As Méndez wrote:

Coolio gets right down to business, asking BTS some basic questions about the origins and history of hip-hop. Whether it’s because they’re nervous or clueless or both, the room goes quiet. But it’s not long before Coolio is interrupted by class clown V, who chimes in with a “turn up” that makes Coolio pause his pop quiz to get the kid in line. He asks V if he even knows what “turn up” means, to which V replies, “Let’s go party?” Some of the other members chuckle, the others shake their heads in embarrassment. Coolio is not amused. He orders V to do 25 pushups, and the group’s eyes collectively widen. Shit just got real.

“Do you even know what that means?” is a fair question to ask of K-pop stars, or idols, who often talk the talk without really knowing what they’re talking about. This is not to say these stars aren’t genuine or talented artists, but the K-pop industry is about selling a package. Idol groups are formed by finding raw talent and the right look that can be preened, polished, and trained to deliver that package. When forming a hip-hop group, it’s not as important to know and respect hip-hop culture as it is to be able to sell it.

BTS continued their American Hustle Life education with rapper/producer Warren G, a pioneer of West Coast hip hop, and renowned vocal coach and music consultant Iris Stevenson, who served as the inspiration for Sister Mary Clarence in Sister Act 2.

American Hustle Life starts out rough for BTS, who are “kidnapped” by the guys who will eventually become their LA comrades. Much of the series is edited for laughs but many scenes also show that the boys are taking their lessons seriously and developing deeper appreciation of hip-hop. This is especially apparent after Stevenson’s singing lessons: the boys appear to appreciate their new vocal skills, but are also touched by Stevenson’s patience, kindness, and maternal spirit. They respect her as a master of her craft. To them, Stevenson, or “Iris seonsaeng (teacher)” as they called her, is one of the newfound fans they hope to most impress.

Unlike the hard-nosed and strict Coolio, Warren G is another seonsaeng whom BTS hopes to impress. Warren G calmly taught the boys the true meaning of hip-hop, as well as the ways in which the genre is wrongly mischaracterized by racism and negative stereotypes. As RM told HipHopPlaya in 2015:

I wanted to ask Warren G a lot about hip-hop. Like Warren G stated, things like ‘shooting guns, doing drugs, robbery’ aren’t things that are hip-hop itself, but a negative side that’s included within hip-hop. It’s like an uninvited guest that shoved its way into hip-hop, but people said that that’s hip-hop. He also told me that hip-hop is something that’s open to everyone despite what race you may be or what language you may speak. I heard a lot of great things from him besides those as well. Although it may seem like a very obvious thing, but the weight of it just felt different when Warren G said it. And after everything he would say, Warren G attached “It’s all Good.” When I heard those words from the side, then my mood felt really good. Should I compare it to the feeling of a grandfather telling good stories next to you (laughter).

RM reflected on more of Warren G’s teachings” in another interview:

Interviewer: Although hip-hop is a genre of music, it seems like a type of religion and philosophy. Just what is hip-hop? Just what is it that guys seem to go crazy over it?

RM: Defining hip-hop is the same as trying to define love. If there are 6 billion people in the world, then there are 6 billion definitions of love, and like that, each definition of hip-hop is different for each person. Of course, it’s possible to give a dictionary definition. In 1970, there was a person called DJ Herc in South Bronx. At a party that he was hosting, he set breaks on a beat and during that break, someone would be rapping, someone would be dancing, and someone else would be doing graffiti… That’s how hip-hop was born, and they call that the 4 elements of hip-hop, but dictionary definitions like these is something anyone knows, but to explain that spirit… In one word, it’s something that can’t be explained. It’s a way that expresses me as well as being a meaning for freedom and rebelling. Because it’s something where people play and have fun with, it can have messages of peace and love placed in it. If you compare it to a Pokemon, it’s like a Ditto. Personally, hip-hop to me is the world. The world that I’m living in… It’s difficult, right? To be honest, it’s still hard for me too.

Interviewer: Maybe it’s because I don’t know much about hip-hop, but there are many aspects of hip-hop culture or clothing that I’m unable to understand easily. The hanging gold necklaces, gun fires, images like that… I also don’t really understand the term ‘swag’ that is used often.RM: The culture of shooting guns and doing drugs is not the actual self of hip-hop. It’s just become a by-product that appeared around hip-hop music, it’s not the actual self of hip-hop. Although there’s a certain image that pops up clearly when you think of hip-hop fashion, that’s also becoming something that’s more broad. Look at A$AP Rocky or Kanye West. They don’t wear pants that drag around any more. To understand ‘swag’, you need to understand what kind of meaning ‘making it on your own’ has in hip-hop. Making it on your own is a very cool and important concept in hip-hop.

I don’t know whether RM has ever been interested in Black music and Blackness beyond rap; but, RM’s experiences in Los Angeles immersed in West Coast rap culture and learning from hip-hop legends clearly had an impact. For instance, when RM put out his mixtape, a series of songs that reflected his own inner turmoil, loneliness, and stress from rival rappers doubting his credibility, he cited India Arie’s “Just Do You” as a source of inspiration.

“It’s a song that gave a lot of comfort to me when I felt confused,” he said to HipHopPlaya. “I believe that the message of this song gave a lot of influence towards this mixtape. That’s why the song that represents the entire message for this mixtape is ‘Do You’.”

India Arie is relatively obscure even by American standards. Despite mainstream success with her 2006 hit “I Am Not My Hair”, she has remained a primarily independent artist. She is an even less likely source of inspiration for K-pop, where most references draw safely from Top 40 hits; that RM drew inspiration from her music speaks to his growing knowledge of Black music and culture.

After his time in LA, RM also apologized for his past missteps including for his youthful boasting about “talking Black.” He said he had to come to terms with the fact that his words might have been hurtful, and seemed resigned to being unable to change the past; all he can do is go forward. Most importantly, he said he holds himself responsible for what he’s done.

Finally, it seems a K-pop group understands the sensitivity they need for entering the world of Black culture. They could also address issues facing Black people today, including Colin Kaepernick’s kneeling, #BlackLivesMatter, and police getting off scot-free after killing black men and women. K-pop idols should be at the forefront of supporting Black lives — the lives of their fans — particularly if they seek to involve themselves in Black music and culture. To adopt Blackness in any form is also to adopt the issues that affect black people. Black people didn’t gain our unique swag just by happenstance; the ways we express ourselves come from centuries of finding alternative ways of keeping our dignity through unspeakable horrors, and of figuring out how to express ourselves in sly, inventive ways. Our culture comes from the little we were able to retain from crossing the Middle Passage. Blackness is, in a nutshell, achieving greatness amid struggle and constantly finding ways to achieve success in a society that hates us. Through pressure and stress, unexpected diamonds were created. But our diamonds — our culture — are things we are not willing to have mined without reciprocation. To get in the vicinity of these diamonds, you have to earn it.

BTS isn’t shy about making socially conscious music. “Our song lyrics are not 100 percent based on our personal experiences. However, a lot of the lyrics have been influenced by our experiences,” said Suga to Soompi‘s E.Cha. “…We’ve tried hard to tell the stories of our generation and our age group in present-day society.”

BTS’ music frequently deals with topics that aren’t normally expressed in K-pop. As Billboard‘s Tamar Herman wrote when describing RM’s single with Wale, “Change”:

“Though most K-pop acts shy away from politicizing their music, or even touching on seemingly controversial topics, the Rap Monster-led K-pop act has addressed politics and cultural issues in their songs on multiple occasions, with a particular focus on youth-related issues such as mental health, bullying and suicide. The atypical approach has made BTS fan favorites in the U.S., leading to them becoming the highest-ranked K-pop act ever on the Billboard 200.”

“Change,” which was released this March, not only features RM’s commentary on Twitter bullying, but it also includes Wale’s reflections on the state of black America, including recent police shootings and other injustices. “With the duo currently criticizing the ‘alt-right,’ Twitter’s ability to ‘kill,’ ‘racist police’ and declaring ‘no faith in the government,’” writes Herman, “the unrestrained hip-hop track is one of the most progressive songs yet from the socially aware boy band BTS.”

As RM told Teen Vogue‘s Taylor Glasby, the collaboration was Wale’s idea — a credit to BTS’ relevance. “When he suggested the collaboration, that was a real shock,” he said. “I thought about it, [and was] like, should we do a party song? But I wanted to something different. The title is ‘Change’–in America. They’ve got their situations and we’ve got ours in Seoul, the problems are everywhere and the song is like a prayer for change. He talks about the police, and problems he’s faced since he was a child. I talked about Korea, my problems, and about those on Twitter who kill people by keyboards.”

Setting the Precedent

BTS is on the right track towards learning from K-pop’s past mistakes and working to earn their stripes with Black listeners as they cross over into the international realm; but, BTS could also set a precedent for other K-pop groups to do the same.The group has the potential to be that special group that teaches their fellow K-pop idols a thing or two about what true respect for hip-hop looks like.

Consider what artist and musician Tony Jones — one of BTS’ LA mentors in American Hustle Life — said to Soompi in 2014:

I thought every other group and artist in Korea that did K-Pop was like that and that talented. I was wrong. Not to talk about any other group, but they’re just different. BTS has so much to offer. They really studied hip hop culture. I want to meet the person behind them because the producers and the directors are finding the beats, and everything they’re doing is really American. I also really think that they can come over to the U.S. and do music if they can learn English in the future. They’re that good. They’re that talented. Afterwards, people were like “Look up BAP, look up EXO, or G-Dragon,” and all these groups. I checked them all out, and it wasn’t the same for me, you know. They’re talented as well, but it wasn’t the same reaction that I got.

…They took from New Edition, from Boys to Men, they also took from A$AP Rocky. They just took everything and put it together. I don’t know if that was the plan or the boys were that talented but it’s lucky they came together. It’s brilliant. I really think that K-Pop will blow up more and it won’t be a local thing anymore. It’s going to grow because of BTS.

…Those boys and the staff really studied American culture and they do it very well. I’ve seen people from different countries try to mimic it and try to replicate it and try to rap the same, sing the same, and act the same, but it’s not happening. Those boys really studied and really got good at it. They’re all talented from top to bottom. There’s not a weak link in the group. So it’s very interesting. They’re really good.

Warren G is right: anyone can rap; but, not everyone has the dedication to the craft or the willingness to learn about Black history and culture. This could also be what separates BTS from their more formulaic K-pop cousins. If so, one can only hope that other groups will get the hint.

The world of K-pop can be a Matryoshka doll of racism, colorism, fanaticism, fetishism and exoticism, all surrounding a core of general ignorance. To dig through those layers as a Black American can be exhausting. Throughout my writing of this post, I’ve wondered if I was giving BTS too much wiggle room — or, perhaps, not enough. I did what every Black person interested in BTS must do: judge the group based on where they started and where they are now. I believe the group has had its hard knocks, but they’ve learned and taken responsibility or those errors; and, taking responsibility for your worst mistakes has to count for something.

It’s this growth that put BTS in a prime position to gain even more Black followers than they already have, and I’m not just talking about young Black girls attracted to the boyfriend fantasy that K-pop boy groups excel at. With collaborations like the ones with Wale and Desiigner, BTS has officially gained crossover appeal and a certain amount of credibility. Not “Black card” credibility; plain old credibility, which can help turn a Wale or Desiigner fan onto BTS’ music. These types of Black artists speak to a broad set of Black listeners. If you’re a young follower of rappers influenced by trap and the new wave of southern hip hop, then BTS is trying to convince you that they have a toe in that world, too. If you’re a rap fan who’s on Wale’s speed — between your 30s and 40s, a little more conscious, and a little more jaded and world-weary than some younger fans — BTS can appeal to you as well, despite their youth.

Overall, BTS wants Black America to know that they get it. They’ve had the teachings from rap royalty. They’ve got people like Warren G in their corner. They’ve gained more respect for the artform, and it shows in their latest work. BTS’ most recent album, Love Yourself: Her, has a melodic quality that’s in line with the sounds coming from SZA, Daniel Caesar and Bryson Tiller, as well as a punch of anger — the original version of MIC Drop has a backing track that sounds like a mashup between Kanye West, Flo Rida and Timbaland, and lyrics that show that the group has a certain amount of grit that, at the very least, can intrigue new listeners. Most importantly, the album sounds authentic, which will make them appealing to Black audiences.

BTS has learned what it means to make great hip-hop. As RM said, even if there is a dictionary definition for hip-hop, the true spirit of hip-hop can’t be explained. Hip hop isn’t about affectation and it isn’t about pretense; it’s about being real and being true to who you are.

Is BTS’ education on black America done? On the contrary: BTS is still learning. In fact, that education will never be over for the group, and they are bound to make a new set of mistakes the more they fight for U.S. dominance. They will always have more to learn about their Black audience, and continue to unlearn some of the problematic ways that K-pop in general handles Blackness. But, if their experiences on American Hustle Life are any indication, BTS has genuinely learned how to be true to themselves, and it shows in their new, broader-reaching, and more culturally responsible sound and outlook.

And, if BTS can learn to be true to themselves, the rest of K-pop can learn that lesson, too.

FURTHER READING:Hip Hop and its Complications in BTS’ ‘American Hustle Life’ | CriticalKpop

Monique Jones is founder of Just Add Color, an online magazine dedicated to discussions of race and diversity in pop culture media. Follow her on Twitter at @moniqueblognet.

Learn more about Reappropriate’s guest contributor program and submit your own writing here.