Hundreds of people took to the streets of Paris this week to protest the killing of 56-year-old Liu Shaoyo, a father of five and a Chinese national who was shot to death by French police in his home. Liu was reportedly holding a pair of scissors and descaling a fish for the family’s dinner Sunday night when plainclothes police banged on their front door.

One of Liu’s surviving daughters recounted the events that followed in a press conference held earlier this week:

“They began to bang on our door and then we heard something we didn’t know who it was, by that time I was stricken with panic.

“My father was really trying to hold back the door and then the door opened all of a sudden. A shot was fired. All of this happened in just a few seconds,” she was quoted as saying by AFP news agency.

Liu’s daughter went on to say that it wasn’t immediately clear to the family that the men at the door were police. Police claim that Liu was shot after charging at them with the scissors, but Liu’s family refute that account. They say that Liu was shot moments after police broke into the home and before most of the family had time to react.

The Chinese French community is outraged by the apparent act of excessive and unprovoked police force. Nearly 150 demonstrators engaged in a candlelight vigil and street protest that began peacefully Monday evening, but which eventually turned violent: three police officers were reportedly injured and a car was lit on fire as protesters were caught on camera hurling bottles. 35 were later detained in relation to the protest. (For the record, I do not condone protester violence — I am a supporter of non-violence.)

The incident, which Chinese French community view as the latest in a pattern of overt and oblique racism that their community has endured, resonates for those of us across the Atlantic Ocean in America; and, rightfully so. One can hardly fathom a series of events that would rationalize Liu’s shooting as rational. More importantly, even were police accounts of Liu’s behaviour moments before his murder, this would not justify his death. Even if Liu were armed with a pair of scissors and non-compliant with police officers, this would not rationalize his murder.

Indeed, the killing of Liu Shaoyo reminds of a similar shooting death that occurred earlier this year in America: 60-year-old Jiansheng Cheng was gunned down by a private security guard while playing Pokemon Go at a local apartment complex for alleged trespassing. Indeed, while those who are killed by police are predominantly Black and Brown — Black, Latino and Native people died at the hands of police at several times the rate of White people in 2016 — Asian Americans are not immune to falling victim to excessive police force. The Guardian reported last year that 24 Asian American and Pacific Islander people were killed during police encounters; all were AAPI men, and many were Southeast Asian American or Pacific Islander. Among them was Barry Prak, a 27-year-old Cambodian American community activist who had been active in protesting excessive policing prior to being shot and killed by Los Angeles Police Department officers. In 2015, 20-year-old Feras Morad was shot and killed by police after he suffered a negative reaction to psychedelic mushrooms. Earlier that year, 57-year-old Sinthanouxay Khottavongsa died after he was Tasered by a police officer allegedly because he was holding a crowbar; family say that Khottavongsa was helping friends with repairs at the time. In 2006, 19-year-old Fong Lee was riding his bicycle with his friends when he was chased down, shot and killed by a Minneapolis police officer. In 2003, undercover police officer Duy Ngo was shot and left for dead by fellow officers when he was mistaken as a gang member.

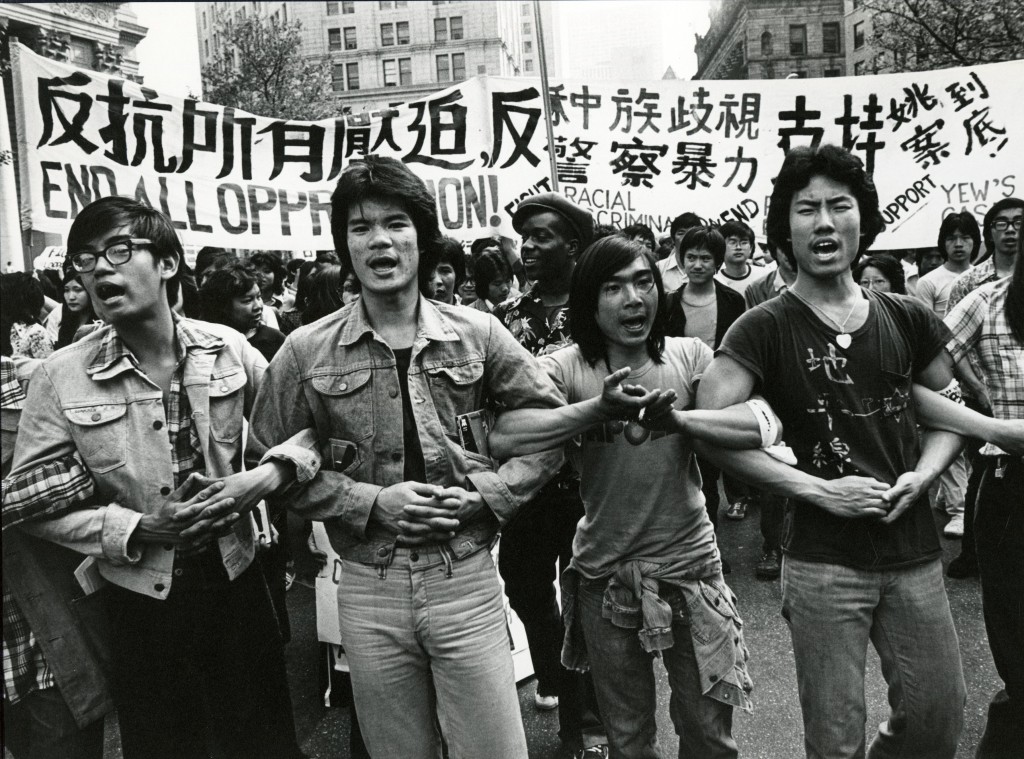

These examples, and many others, demand that Asian Americans take a stand on police accountability; these examples demonstrate that we are already a part of this issue whether we like it or not. These examples remind us that many Asian Americans — and particularly many Asian American men — are also vulnerable to unjustified police violence influenced by implicit bias and racism. Indeed, in the 1970’s, violent racial profiling by police against Chinese American male youths was so pronounced, thousands of Chinese Americans took to the streets in metropolitan Chinatowns demanding greater police accountability and an end to police violence.

Despite this history, the modern Asian American community has become frustratingly divided on the topic of police accountability. Following a string of high-profile shootings of unarmed Black men and women, the Black Lives Matter Movement was formed to hold the criminal justice system accountable for the many ways in which it enacts violence against Black and Brown bodies. Many — myself included — have urged the Asian American community to add our voices to the growing chorus of activists who oppose anti-blackness and the use of police violence as a tool of institutionalized racism. My primary reason for this position is simple: so long as we allow that police may take Black lives at whim, the lives of Asian Americans can not be considered safe, either.

And yet, our community still has so much work left to do when it comes to anti-blackness. We must acknowledge our decades-long political allyship with Black and Brown communities, and do better to maintain the bonds of that solidarity. We must put aside our instinctive rhetorical defenses of police officers who are reckless with civilian life. We must stop chasing the status of honorary Whiteness by distancing ourselves from Black and Brown communities. We must stop identifying primarily with mainstream Whiteness. We must work to see our own humanity as it is reflected also in the humanity of Black and Brown men and women. We must stop blaming the victims. We must stop doing the work of the model minority. We must refuse to support any institution that might make an empty promise of privilege for Asian Americans on the backs of all other people of colour.

There is no defense for a status quo that undervalues civilian human life. There can be no protection for a system that expects unquestioning compliance of a militarized police authority under threat of physical assault, imprisonment, or death — particularly when those who fall victim to such violence are overwhelmingly people of colour. Such a system does not set as its goal our protection; instead, it exists primarily to restrain and subjugate the most marginalized among us. Asian Americans must remember that our relative safety from police violence (as compared to that of other communities of colour) is precarious and illusory at best. A system that doesn’t value Black lives can never truly value Asian American lives either.

The Chinese French community has been activated this week to fight back against excessive police violence. Many are in the streets forcefully — and peacefully — demanding justice for Liu Shaoyo, as well as greater police accountability and an end to racist policing practices.

When will the Asian American community be galvanized once more to do the same?