On August 26th, Americans marked the 95th anniversary of the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, after a long and hard-fought battle by suffragists. With its passage in 1920, the Nineteenth Amendment declared it unconstitutional for any effort to disenfranchise any voter on the basis of sex. In 1971, Congress christened August 26th as National Women’s Equality Day to mark the passage of the Amendment and to celebrate the winning of the right to vote for female voters.

I think it’s extremely important to celebrate the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, without which female voters would still be denied a political voice. We should not forget America’s roots. At the founding of this country, the right to vote was limited to land-owning White men; the subsequent two centuries have seen a progressive expansion of civil rights (including voting rights) to encompass marginalized American groups, and this country has been made the better for it. The Nineteenth Amendment was — and is — a crucial victory in the larger war to establish and defend voting rights for disenfranchised groups, and fully deserves our celebration.

But, while the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment did indeed create equality for female voters, it only established ballot box access for some female voters. When we brand August 26th as “Women’s Equality Day”, we forget that voting rights were not won for all women on August 16th, 1920. For many of this nation’s women of colour, voting rights would take up to a half a century longer to be realized; and for many of today’s women of colour, equal ballot box access remains stymied.

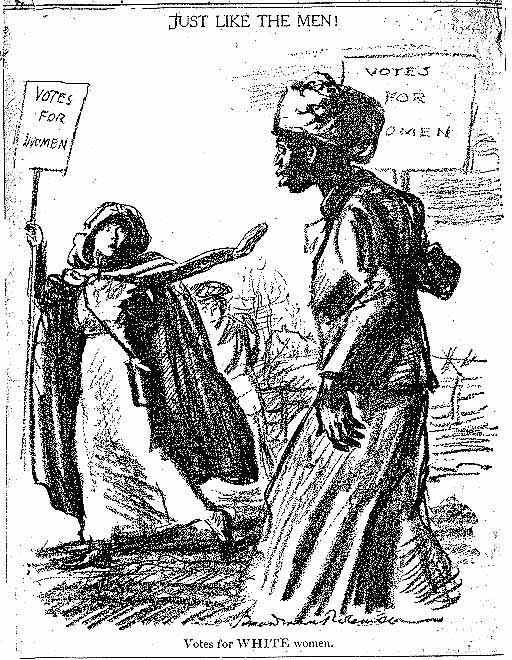

The passage of the Nineteenth Amendment was the culmination of nearly seven decades of work by suffragists starting in 1850, including many Black female suffragists who formed groups to aid the fight to win the female vote. However, the mainstream suffrage movement was dominated by White female activists who excluded the work of Black suffragists, and even on occasion employed racist rhetoric to justify the White female vote. Writes the National Women’s History Museum:

Despite [their] strong support for woman’s suffrage, black women sometimes faced discrimination within the suffrage movement itself. From the end of the Civil War onwards, some white suffragists argued that enfranchising women would serve to cancel out the “Negro” vote, as there would be more white women voters than black men and women voters combined. Although some black club women participated actively in the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), the NAWSA did not always welcome them with open arms. In the 20th century, the NAWSA leadership sometimes discouraged black women’s clubs from attempting to affiliate with the NAWSA. Some Southern members of NAWSA argued for the enfranchisement of white women only. In addition, in the suffrage parade of 1913 organized by Alice Paul’s Congressional Union, black women were asked to march in a segregated unit. Ida B. Wells refused to do so, and slipped into her state’s delegation after the start of the parade.

When the Nineteenth Amendment was finally passed, female Americans were nominally enfranchised regardless of race. But, while many White female voters enjoyed largely unfettered access to the ballot box, new and existing laws aimed at disenfranchising voters of colour meant that women (and men) of colour remained profoundly disenfranchised despite the Amendment’s passage.

For Asian American and Native American men and women, laws that denied citizenship on the basis of race formed the early basis of voter disenfranchisement that persisted long past 1920; without the capacity to hold American citizenship, members of these communities could not vote. Beginning in 1876, Native Americans were legally ruled non-citizens of the United States, and laws that barred Native Americans from US citizenship continued to stand for nearly half a century afterwards. Only in 1924 — four years after the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment — were Native men and women recognized as American citizens by birthright with the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act.

The vast majority of Asian Americans living in the United States in the late nineteenth century were foreign-born immigrants, and who were prohibited from naturalizing as American citizens by laws such as the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. This and other laws also excluded new Asian immigrants, and in particular the 1875 Page Act denied entry for Asian women. Coupled with laws that prohibited intermarriage or interracial sex by race, the Asian American community in America was effectively engineered by law to remain a bachelor society of men, with neither naturalization nor birthright citizenship widely accessible for the community at-large. Although the landmark Wong Kim Ark Supreme Court case established the standard of birthright citizenship in this country for US-born children (including Asian Americans), this didn’t pertain to the vast majority of Asian Americans living in the country at the turn of the twentieth century who were more likely to be foreign-born. (In fact, the Census reports that the number of foreign-born Americans born in Asia in 1900 actually outnumbers the number of self-identified Asians in the country at the time). Furthermore, in the years following the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, the Supreme Court upheld in 1922 (Ozawa v. United States) and in 1923 (United States v. Thind) that foreign-born Asian Americans could not naturalize as American citizens — and therefore could not vote in American elections — regardless of how long they had resided in the country. Only in 1943 with the repeal of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, and in 1952 with the passage of the McCarran-Walters Act were all Asians — including Asian women — granted the right to naturalize as citizens, with voting rights at last nominally accessible by extension.

Yet, as we can best observe through a consideration of Black American history, legal enfranchisement does not necessarily translate into an end to voter disenfranchisement. Although Black men were legally enfranchised by the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870 and the Nineteenth Amendment in theory extended that right to Black women, in practice, Black voters remained disenfranchised for nearly another century after the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment. Hoping to deny Black voters political representation, state and local lawmakers instituted poll taxes and literacy tests aimed specifically at silencing the Black vote; White voters who might have been disenfranchised by these local laws were exempted by carefully worded grandfather clauses. Similar state-held literacy tests — such as laws requiring English language proficiency at the ballot (even though America does not hold English to be its official language) — discouraged Asian voters even if they held American citizenship, and also profoundly disenfranchised Mexican American and Native voters. In addition, Native Americans also remained disenfranchised long after the 1924 Indian Citizenship Act by state laws refusing to recognize the state citizenship of indigenous people — these laws persisted at the local level until as late as 1948.

Where state laws failed to silence the vote of people of colour, violent lynch mobs filled in the gaps.

Only in 1965, with the passage of the landmark Voting Rights Act were many of these voter disenfranchisement efforts found to be illegal, and were voters of colour — including most women of colour — at last granted broad (if still incomplete) voting rights.

The passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 brought voter equality for America’s White women. It would take another 45 years for America’s women of colour to see any real semblance of equal voting rights.

95 years later, we should celebrate the hard work by feminist suffragists to win women the right to vote on August 26, 1920, and this post is not intended to detract from those pioneering efforts. However, when we label August 26 “Women’s Equality Day”, we suggest that the fight to enfranchise female voters was won and ended on August 26, 1920. When we make the unqualified assertion that American women won voter equality on August 26, 1920, we imply that all women are White women and we erase the disenfranchisement of women of colour that persisted for decades after.

The passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 was necessary — but not sufficient — to bring about women’s equality in America. It was only one (if an admittedly extremely important) step in a much longer journey to enfranchise all of America’s women voters. We should celebrate and honour the work of suffragists for this important legislative victory in 1920, but we should not do so in a way that denies the experiences and the political legacy of women of colour.

Rather than to see Women’s Equality Day as a celebration marking the end of a long fight to secure women equal rights, I see it as a beginning: a call-to-arms to continue the fight to establish and defend the civil rights of all women (and men), then and now. Even though the right to vote is now constitutionally protected for women, gender disparities between America’s men and women remain; those disparities are exacerbated among women of colour. Women still remain underrepresented in America’s political system. Women are still paid 78 cents to the dollar paid to men. The Equal Rights Amendment remains unpassed. Women — particularly women of colour — are still trapped beneath a persistent professional glass ceiling, and we still face significant racial and gender-based discrimination in the workplace. Women of colour voters (and our male counterparts) still endure profound voter disenfranchisement by contemporary voter identification laws and de facto literacy requirements at the polls, a situation made even more dire by recent weakening of the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Women’s equality wasn’t found on August 26, 1920. Many of us are still seeking it, today.