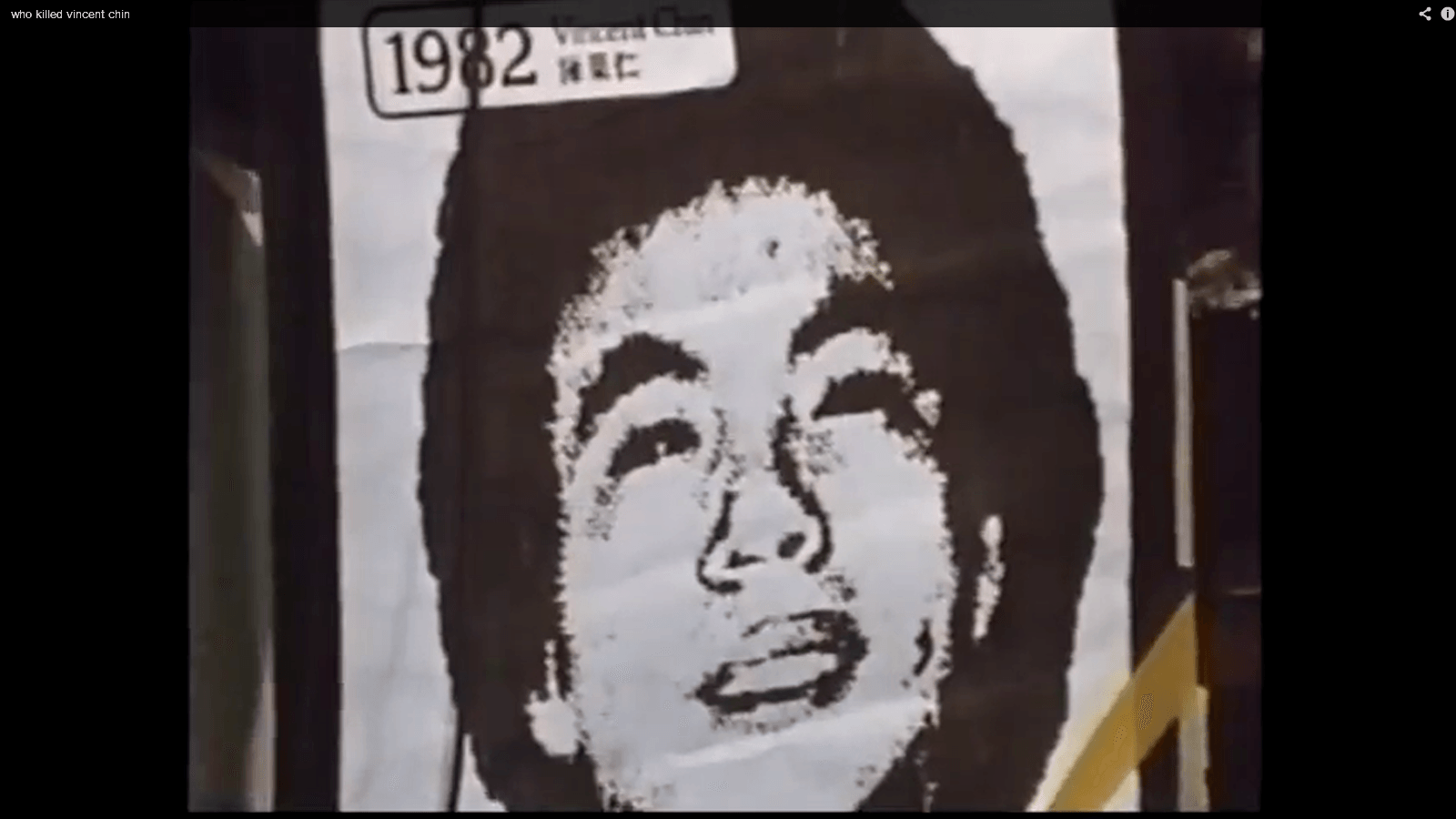

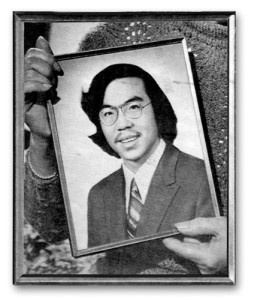

33 years ago today, Vincent Chin died at the age of 27.

Chin had been in a coma for four days after being attacked by Ronald Ebens and Michael Nitz. The two Chrysler factory workers reportedly said to Chin, “it’s because of you little motherfuckers that we’re out of work” — a reference to competition between American and Japanese auto workers, although Chin was Chinese American — moments before the father-and-son team fatally bludgeoned Chin with a baseball bat.

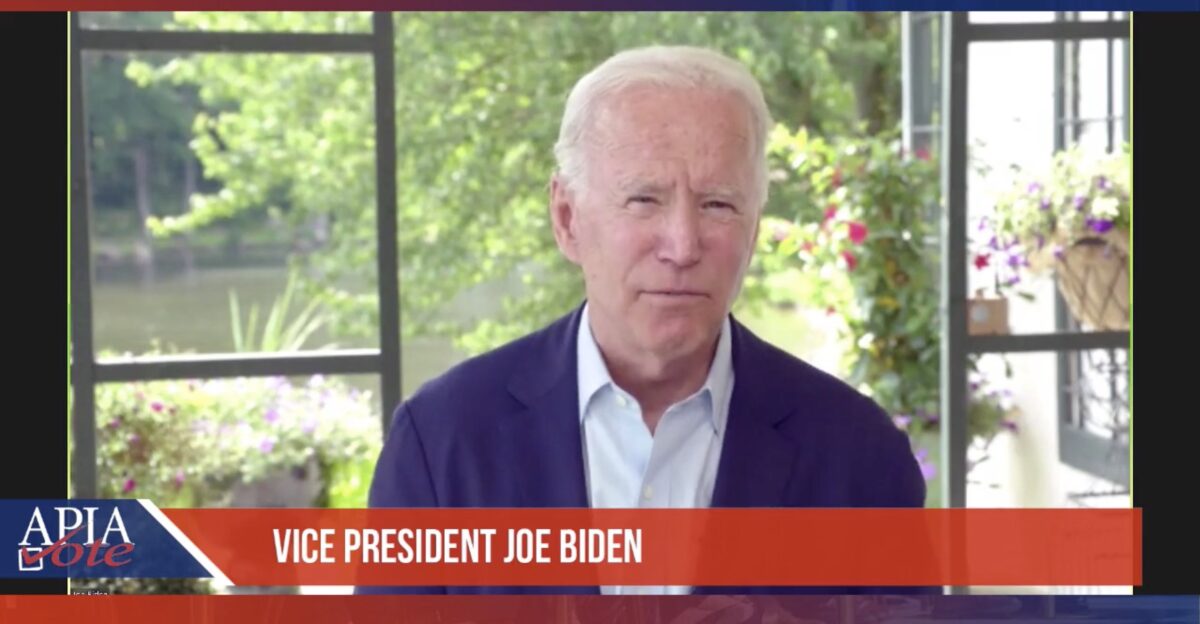

Justice was never found in the hate crime murder of Vincent Chin. Ebens and Nitz paid a $3000 fine for killing Chin. Neither man ever served a day in jail. (To learn more about Vincent Chin’s murder, check out Who Killed Vincent Chin?)

For many young AAPI activists, the injustice surrounding Vincent Chin’s death and its aftermath serves as a formative moment. Yet, most Asian American youth only learn about Vincent Chin’s death in their Asian American Studies courses (if they have access to them), or from blogs like this one. So, it is critical that every year, community elders remind us of Vincent Chin, to remind us of the work that remains to be done.

But, mere days after the fatal shooting of nine Black congregants at Mother Emanuel A.M.E. in one of the most devastating acts of racially motivated domestic terrorism in recent memory, I’m compelled to commemorate Vincent Chin’s death somewhat differently this year. Today, I feel obligated to not just remember Vincent Chin alone, but to place his life alongside the lives of far too many others who have been lost to White supremacy and racial hate.

Too often, we in the AAPI community recount Vincent Chin’s story in isolation, which can unintentionally perpetuate the myth that this crime — devastating though it was — is rare for the Asian American community or that no such crimes of such magnitude have occurred since. Yet, nearly 6,000 hate crimes are reported to the FBI each year (with numerous others likely going unrecognized or unreported); nearly half are racially motivated. In 1995, nearly 8% of racially motivated hate crimes reported to the FBI involved anti-Asian American or Pacific Islander bias, in a year when we were only 3.5% of the national population. Today, anti-AAPI hate crimes are roughly 5% of federally reported hate crimes, although for some AAPI ethnic groups (such as for South Asian Americans, Muslims or Sikhs), racially-, ethnically, and religiously-motivated hate crimes have increased at an alarming rate.

Our community — like too many communities of colour — has endured far too many bias-motivated crimes in the three decades since Chin’s death: the anti-Sikh shooting that claimed six at Oak Creek on August 5, 2012; the stabbing death of 16-year-old Vietnamese American Bang Mai in Boston in 2004; the brutal drowning murder of 62-year-old Du Doan in 2007 by a self-described skinhead; the murder of Filipino American postal worker Joseph Ileto as part of a hate-motivated spree shooting in 1999; the dragging and choking murder of 49-year-old David Kao by four teenagers in 2009 in Flushing, New York; the 2001 shooting of Balbir Sodhi Singh; the subway killing of Sunando Sen in 2012; serial rapists who targeted Asian American female victims in 2000, 2006, 2011, and 2012; the shooting of undercover police officer Duy Ngo in 2003; the beating of two Chinese American men in Douglaston, Queens in 2006; the stabbing and shooting of Hmong American hunter Cha Vang in 2007; the anti-Muslim and anti-Sikh hit-and-run assault of 29-year-old Sandeep Singh last year; the serial assault of six Chinese American women in New York City last month; the serial assault of four Asian American women last week; and so many more.

Sadly, few of these Asian American victims of racial hatred receive the kind of attention and grassroots mobilization that Chin’s did. Few of us know their names.

Still more victims likely go completely unnoticed by our criminal justice system. Most young Asian American victims of bullying, for example, experience it in our nation’s classrooms, where racial violence may not rise to the level of criminal behaviour and therefore may go ignored or unreported by teachers. As for adults: relating in part to linguistic barriers, the Model Minority Myth (which stereotypes Asian Americans as inscrutable, and therefore oftentimes unvictimized) or the difficulties in proving a hate crime, most hate crimes go either unreported by their victims or unrecognized as racially motivated by local law enforcement. Colorlines reports:

The Asian American Legal and Defense Education allege, however, that Anti-Asian violence is widely underreported at both the individual and state level. The reasons are manifold: Asian American victims may not be comfortable with, or capable of reporting their experiences because of the lack of bilingual law enforcement personnel, mistrust of local police, fears of trouble over their immigration status, and a general lack of awareness around hate crimes and federal civil rights protections. Furthermore, despite the passage of legislation mandating the collection of federal hate crimes statistics, many states and localities have not made rigorous efforts to prosecute and collect data on anti-Asian violence.

Even when hate crimes are reported, rarely is justice fully served. Vincent Chin’s killers were prosecuted before hate crime legislation existed, which (along with cronyism and systemic racism) contributed to the leniency of their sanctions. In the death of David Kao, prosecutors declined to prosecute the four teenagers who strangled him on hate crimes charges despite their confession that they targeted both Kao and another prior victim because they were Asian.

This further doesn’t consider the fact that more than two-thirds of the thousands of race-related hate crimes that occur in this country every year target Blacks, whose lives matter just as much as our own.

Vincent Chin’s murder deserves our commemoration for the sheer incomprehensible injustice of the crime and its aftermath. Moreover, the events surrounding Vincent Chin’s death deserves a hallowed place in Asian American history for its mobilization of the AAPI community. In the wake of his killing, Asian Americans joined together across ethnic and linguistic barriers for one of the first times in modern Asian American history to seek justice for Vincent Chin.

Vincent Chin’s life and death galvanized Asian Americans not because his killing was rare, but because his case remains all too devastatingly common. Vincent Chin’s murder resonates because his story is familiar. We have all experienced the kind of senseless and brutish racism that would threaten life and limb.

Thus, the Vincent Chin case remains in our memory not simply for the facts of his murder. Rather, we remember Vincent Chin’s story each year because it was a uniting force for our community: one that brought together AAPI in a virtually unprecedented show of solidarity and allyship with one another, all to seek out justice and social change.

This year on the anniversary of his death, I hope Vincent Chin’s memory can do this for us again.

I ask us this year to remember not just Vincent Chin, but the spirit of his story: that all of our lives are worth more than $3,000, or some take-out Chinese food, or a bag of Skittles. This year, I ask us to not just etch Vincent Chin’s name on our hearts, but also the names of all victims of racial hatred. I ask us to remember that no person deserves to die of a hate crime. I ask us to not just redouble our cries for justice for Vincent Chin’s family, but to renew our commitment to ending all racial violence in this country that victimizes all communities of colour.

In the last 33 years, far too many people of colour have died through racial violence and hate crimes. For most, justice still has not been fully served. And while the truth of this is heart-breaking, it is also a reminder that racial justice is — and must be — our common cause. All of us can — and must — unite across racial and ethnic divides to battle the racism that has claimed far too many of our lives for far too long.

I am Vincent Chin. We are all Vincent Chin. Our work is not yet done.