By Guest Contributor: Bao Phi

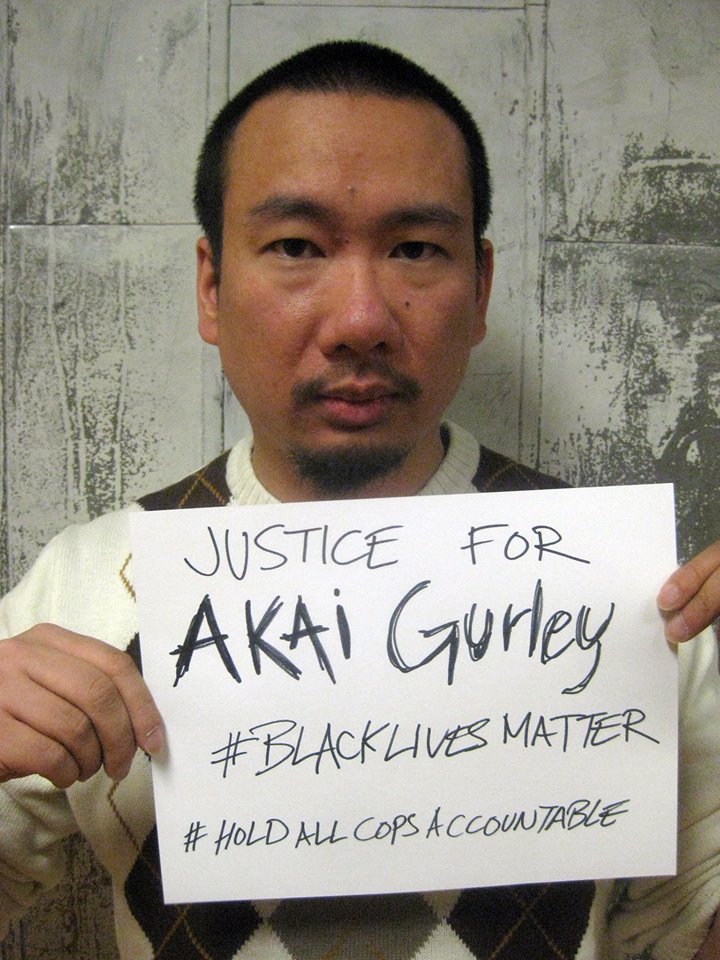

When I began reading that a White House petition had collected 100,000 signatures — many of them reportedly Chinese names — in defense of Peter Liang, a cop who shot and killed an unarmed Black man during a patrol of a housing project in New York, I was perplexed. At a time when the horrible abuse and killing of nonwhite bodies, predominantly Black, was making the news every week, why were so many Asian people defending an officer who wrongfully killed a Black man? And where were these 100,000 people during the wrongful death lawsuit by the family of slain Hmong teenager Fong Lee, killed by a white officer (awarded a Medal of Valor for the killing) with a history of abuse against Black and Hmong people?

But I took a step back, and read about some of the Chinese people who were in support of Liang. Some of them felt he was scapegoated. Some claimed the Liang case was about political maneuvering. Some said they were tired of being pushed around. What was going on here? How was the information on this case being broadcast in non-English media? It’s hard to get more than 100,000 Asians in America to sign onto anything — who got them to sign on to support this officer?

To some, it all may seem cut and dried. Asians are just being selfish and anti-Black again, only coming out of their wannabe white lifestyles to support one of their own. But then what about the cases where Asians have been the victims of police violence that don’t draw anywhere near the same zeitgeist? How do those instances of racist violence against Asians, statistically not as frequent but still racist, fit into our understanding of state sanctioned violence against Asian bodies?

When a person of color (in this case an Asian American) occupies a job in law enforcement and is responsible for the death of a Black body, and suddenly a seemingly significant number of Asian Americans sign a petition for his defense, a lot of messy baggage comes up. On one hand, checking one’s privilege as an Asian American shouldn’t be a prerequisite to understanding that the murder of Black people at the hands of law enforcement, no matter the race of the officer, is outrageous and wrong. If we want to break it down further, we can certainly recognize that we, as Asian Americans, have benefitted from the social justice struggle of Black people and other marginalized peoples in this country (including fellow Asian Americans). Our future is intertwined with the Black community, and therefore we should be standing in solidarity with them and all marginalized people.

But what of those segments of our community who have been taught that taking the side of the police and aligning ourselves with whiteness and the police is our only way of survival? How do we engage those who parallel our path to being American with being (or at least approximating) white? How can we speak to those Asian American community members who believe that the system will take care of us as long as we play along and don’t make waves?

Perhaps we should remember the case of Duy Ngo.

“I’ve always gotten into heated debates with people who spoke ill of the police department or its officers. I put my heart and soul into this career.”

-Duy Ngo, City Pages, 2003

Duy Ngo, a Vietnamese American undercover police officer working in the Minnesota Gang Strike Force, was struck by a bullet from an unknown suspect while working a case. The bullet did not pierce his bullet proof vest, but it knocked the wind from him. After briefly chasing the suspect, he called for backup, and laid on the ground. Two officers in a squad car arrived on the scene, and apparently one of them mistook Duy for an Asian gang member and opened fire on him while he lay on the ground. Duy claims he was struck by eight bullets. Some accounts claim at least six.

During that time, I remember going to Duy’s house to take part in an informational meeting with community members, family members of Duy, and (from what I recall) a lawyer. I was thinking about how often armed forces recruit young men of color from poor and working class families — families like mine, families like Duy’s — to enforce their laws and wars on Black and brown bodies. I listened in horror as a man working with Duy and the family told us details of what happened. From Duy’s account: the squad car rolled up to him with its lights turned off as he lay prone, and the officers failed to announce their presence – all against regulation. One officer then shot several bursts at Duy with a non-regulation MP5 sub machine gun, shattering his left forearm, leg, and groin.

Duy was shocked to find that the police force he was so loyal to quickly turned on him. Rumors spread that Duy was racist or at fault, that he had shot himself to avoid military service, and that it was his fault for working solo and breaking departmental rules. The white officer who shot him with an illegal firearm was put on paid leave for three days. No criminal charges were filed against that officer and an internal affairs didn’t find any policy or procedural violations. Incidentally, this was the same officer who shot a 15 year old boy holding a BB gun a few years prior.

After years of struggling with health issues brought on by the shooting, Duy Ngo sued the department and the city over the shooting to clear his name. He won a $4.5 million settlement in 2007. It “was never about the money,” Ngo commented at the time. “It was about justice.”

For those cynical readers who may be scoffing, know that the injuries Ngo sustained in that shooting led to him being permanently disabled and in pain for the rest of his life. Three years after winning the settlement, Ngo died in 2010 via a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head

…

An often undiscussed factor of the model minority myth, in which statistics of the relative economic and educational success of Asian Americans are manipulated and posited to shame Black people and other people of color, is that the Myth can render invisible, or illegible, the instances of Asian Americans who suffer from racially motivated acts of state sanctioned violence. The wrongful shooting deaths of Fong Lee and Chonburi Xiong at the hands of police failed to generate anywhere near the 100,000 Asian American signatures of protest against injustice that Officer Liang enjoys, and neither case (along with the mysterious death of Jason Yang after he was chased by police) were mentioned in mainstream national news coverage.

Defenders of Officer Liang may argue that in those other cases, those young men had in some way “invited” violence: they were allegedly on the opposite side of the law, or failing to obey police order. They were not acting respectably. By contrast, they assert, Officer Liang is being unduly punished for an accident he committed while on duty.

But how do we then make sense of the tragedy of Officer Duy Ngo? Here was a loyal, veteran Asian American police officer who absolutely believed in the police force. He was on the job, laying prone on the ground, when he was mistaken for an Asian gang member and shot by a fellow officer – who had a history of being trigger happy against people of color. That white officer’s punishment for breaking procedure and firing an illegal firearm on one of his own fellow officers to the point that he was permanently disabled was a three day paid leave.

Some detractors may state that Liang has more in common with Duy Ngo, as both are being railroaded by the system. But in the shooting of Akai Gurley, it was Liang who held the gun that took an unarmed Black man’s life. Ngo’s story demonstrates that in cases like this, the legal system will already be biased in favor of the officer of the law. Duy Ngo was the one shot by a white officer and found himself suddenly on the other side, blamed for his own shooting, even though he had done nothing against procedure.

How can we pretend that if we just pick the side of the police, are loyal and don’t make waves, the same state sanctioned violence inflicted on Black bodies will not someday be applied to us?

The answer is, we cannot, because it has already happened.

The point is not that Duy Ngo’s case is exactly the same as Peter Liang and Akai Gurley’s. Nor is the point that we should only care about police brutality because it also affects our own people. Nor do I argue that Asian Americans and Black people experience racism the exact same way and in the same proportions.

The point is that if we understand history and the transgressions against our own people, we understand that taking the side of the oppressor does not guarantee our protection. No matter how much we are taught to yearn to fully assimilate into American-ness (and implicitly, whiteness), history has shown us that we can never fully become either. We will never be allowed to have the same benefits and entitlements, or the same privileged benefit of the doubt. History reminds us that even when we work for them, they have trouble figuring out which of us is the friend and which is the enemy.

Instead of aspiring to what we will never be allowed to be, perhaps we should stand on the side of those fighting against systemic injustice and oppression. While Asian Americans have and still do participate in white supremacy against Black people, Native American people, and other Asians and immigrant groups, we also have a history of standing with other oppressed communities in the struggle. Standing in solidarity is how we have – and will – help to bring about meaningful change for all people.

Bao Phi is a Vietnamese American refugee, poet, single co-parent, and community organizer raised in the Phillips neighborhood of South Minneapolis. He has been educating himself on, and has been involved in, social justice movements for close to a quarter century, including Justice for Fong Lee and Don’t Buy Miss Saigon.